ISSUE

36

DECEMBER

2025

2025

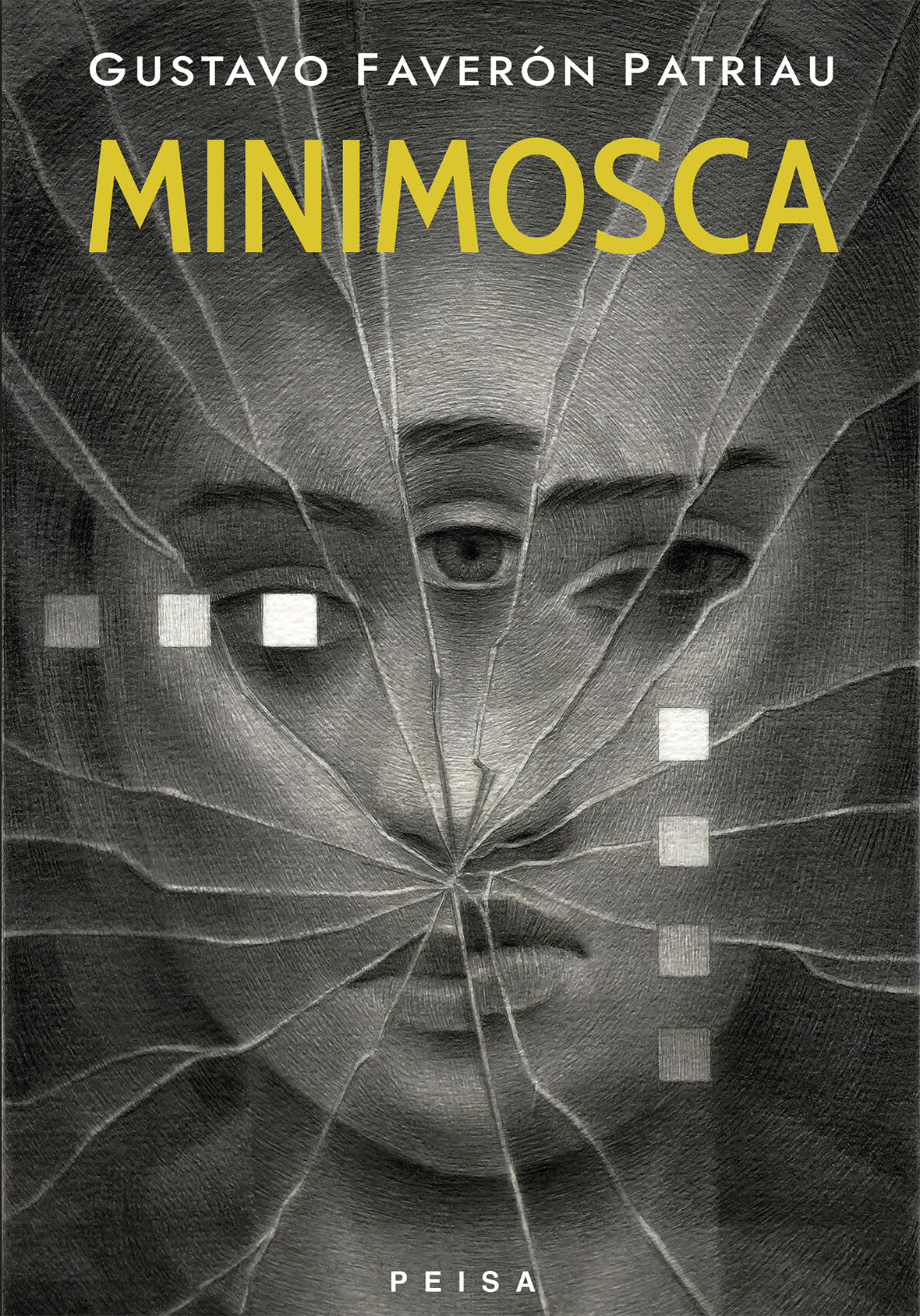

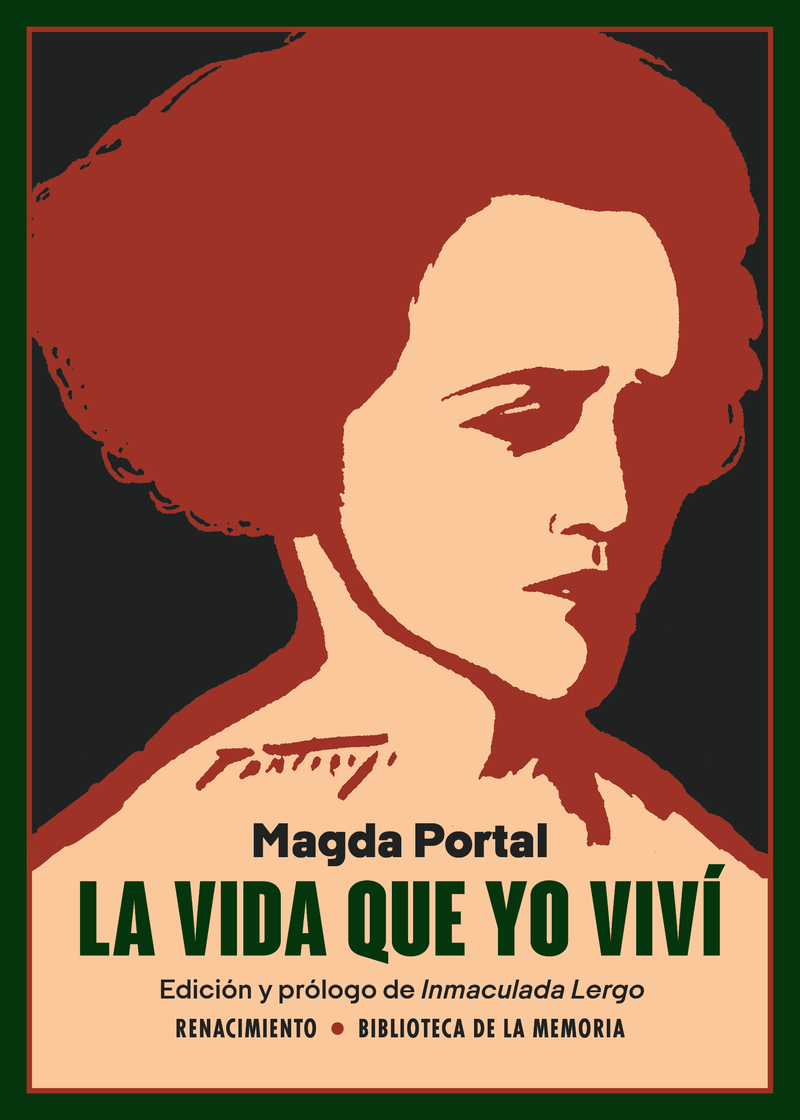

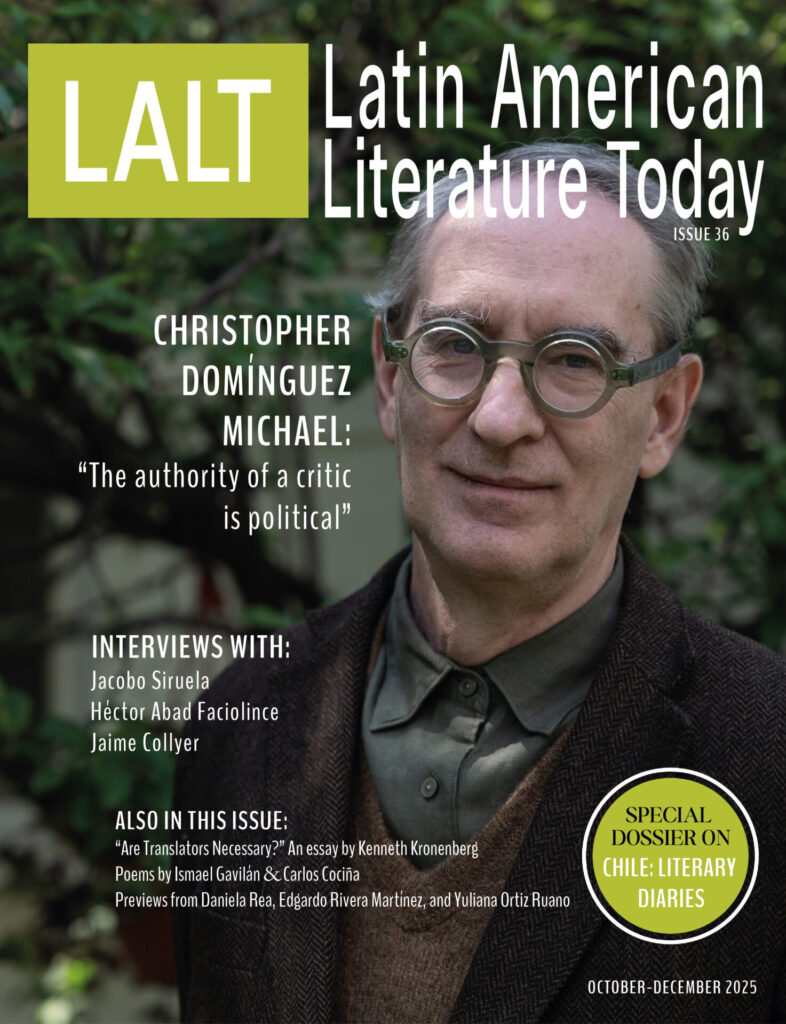

In our thirty-sixth issue, we highlight the role of the literary critic with a cover feature dedicated to Christopher Domínguez Michael. Domínguez Michael is recognized as one of his generation’s definitive critics and intellectuals, and is the author of essential histories, biographies, and anthologies dedicated to the literature of his native Mexico and beyond. This issue’s second dossier focuses on the often-ignored subject of the literary diary, with reflections on the writing of three Chilean diarists: Álvaro Campos, Francisco Díaz Klaassen, and Gonzalo Millán. We also include interviews with Jacobo Siruela, Jaime Collyer, Mariana de Althaus, and Héctor Abad Faciolince, poetry by Ismael Gavilan, Carlos Cociña, Martín Tonlameyotl, Nora Alarcón, and Maria Emanuelle Cardoso, an essay on artificial intelligence by Kenneth Kronenberg, previews of new books in translation by Daniela Rea, Edgardo Rivera Martínez, and Yuliana Ortiz Ruano, and reviews of twelve new books from across Latin America.

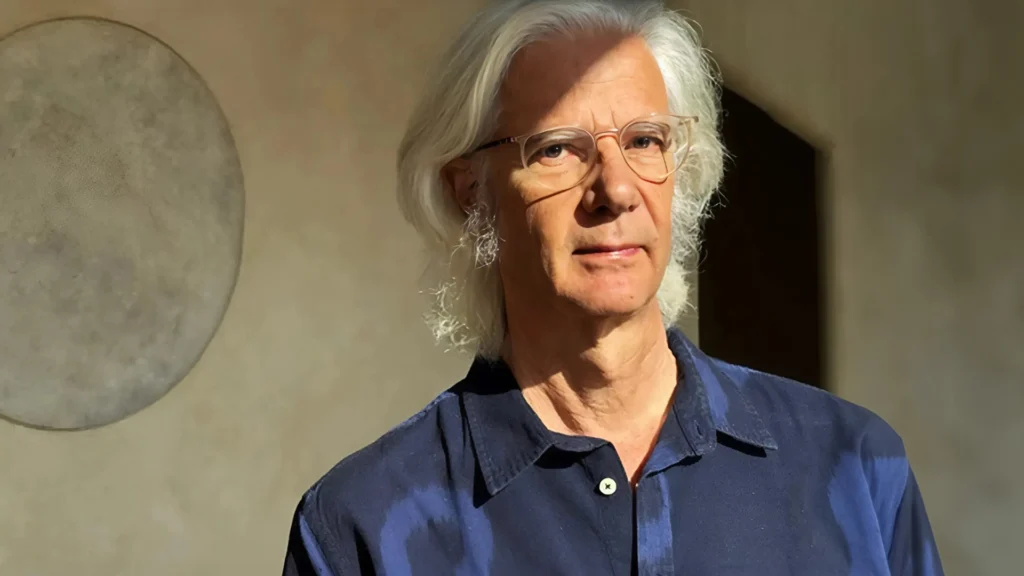

Featured Author:

Christopher Domínguez Michael

His books confirm that he is an aesthete, a jovial philologist, philosopher, and historian without getting lost in any of these fields, allowing ideas to reign over emotion. A global Latin American, and not a “Latin-Americanist,” he is a master of creative interpretation.