JD Pluecker: Silvina, I’m happy to be able to ask you a few questions about your book, Poem That Never Ends, just out from Essay Press on April 30, 2021. I read your beautiful and moving book as a meditation on parenting, motherhood, migration, movement across borders, absence and presence, generational silences, disability, hearing, language; the list could go on and on, as the book is so very rich and multivalent.

JD Pluecker: Silvina, I’m happy to be able to ask you a few questions about your book, Poem That Never Ends, just out from Essay Press on April 30, 2021. I read your beautiful and moving book as a meditation on parenting, motherhood, migration, movement across borders, absence and presence, generational silences, disability, hearing, language; the list could go on and on, as the book is so very rich and multivalent.

I’ve decided to ask you questions about the book in English, because the question of English and your decision to write the book in English delineates the outlines of the initial audience for this collection. As someone born in Buenos Aires but living in New York, this decision says a lot about who is being invited in (at least initially) and who is being placed at a certain remove. It speaks to intimacy and distance really elegantly, I think. For that reason, I thought we would have this conversation in this language, your second tongue, but one you write in quite deftfully and with grace.

A question then: you begin the book with a fragment (or a prose poem, perhaps) entitled “The Sound of Blinds Being Pulled Up Is the First Sound.” We begin with a sound, with something ephemeral, and we begin as readers with a sense of being allowed to peer inside an interior space, though we are also reminded of the person standing in the frame of the window looking out, the person who is opening the blinds. In this fragment, you are speaking with yourself, reflecting on your decision to open the blinds, but also immediately thinking about hearing, about your mother, and your mother’s mother. What did it feel like to write this book, a book that lifts up the blinds on your own family’s interiority? What does it feel like now that it just came out and will meet its English-speaking readers?

Silvina López Medin: Thank you for your kind words about my book, JD. This is the first book that I’ve written almost fully in a language not my own. It traces a sequence of mothers—my mother, her mother’s mother, myself as a mother—in a language my mother doesn’t speak. So, to address your question, in order to write this book, to “lift up some blinds,” I needed this extra layer between language and things that felt hard to talk about, between this tongue and my mother’s tongue, between my mother and I. Or as I say in the book, here “language is a necessary distance.” I guess that as an extension of that, here language perhaps also works as some sort of protective blinds between the audience and me. Not metallic blinds, as the ones in the opening poem, but some translucent blinds: I’m exposed but not as fully as I would be in my own tongue.

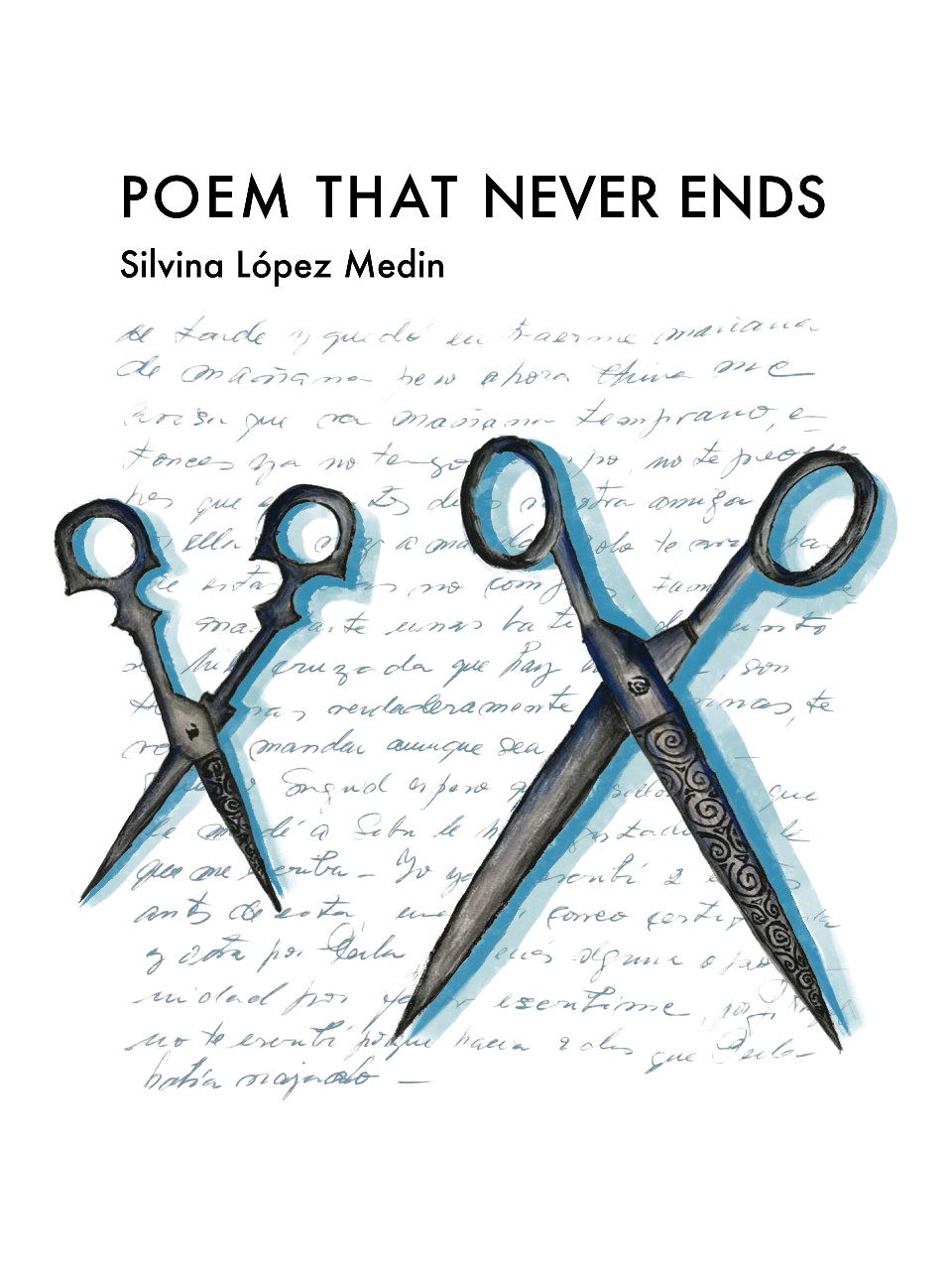

JDP: The form of this book is so variegated and complex, combining image, diagrams, photos, poems, prose fragments, what seem like a series of diary entries. There is even a kind of phantom book within the book, which you create by bolding select words on many pages to sketch a type of erasure poem within the sections that resemble prose. This happens at the level of the page spreads, but also emerges at the end of the book as a Coda that brings together all of the bolded text to create one long poem. Can you talk about the process of the book’s making and how the book arrived to its present form?

SLM: My mother, like my grandmother, has hearing impairment. This inherited trait was not passed to me. The use of a second language in this book works in at least two ways. It generates a distance—my mother can’t read this book—, but at the same time, it’s been a way of connecting with my mother’s experience. I’m thinking about how our hearing is affected when moving between languages, how, for instance, when immersed in English, it’s hard for me to hear well (sometimes I help myself by “reading lips” which is what my mother does to understand others). It was particularly clear when I started my MFA in English and I had to write poems in a language not my own: it was hard for me to hear the music of my own words. This somehow brought me unexpectedly closer to my mother’s experience. There are certain formal aspects of the book that I connect with my family’s hearing impairment—interrogation, repetition, reassembling, the need of visuals—and with the idea of writing as a porous, restless gesture toward what’s never fully grasped. My mother, because of her hearing impairment, questions if she heard what she heard, has to ask for words to be repeated to her, has to reassemble the pieces she hears, needs the visuals to help her understand better. These are some aspects that I was trying to embody in the book formally.

This “phantom book” within the book has to do with that, with pointing toward our partial perception of things, and how in turn those perceptions create layers and interconnect.

JDP: In the book, you include photos your mother took on her cellphone of family photos, which she subsequently sent to you. This additional layer of photos of photos feels very important to the book, because we are constantly being asked to navigate the layers between. In many of these photos, family members are not looking at one another, but rather at the camera or out of the frame. In other photos, family members regard one another. These moments are heightened, because the book teaches us to look at where people are looking and to learn from their gaze. I wonder: what does this attention to looking and hearing have to say about family and about motherhood?

SLM: This is a great observation. I do talk about how the family members look in different directions in the first photo, but I hadn’t thought about this as a thread in the book. Now I realize that in almost all the photos people are not looking at one another. I guess this has to do with a certain dislocation in the way we communicate—I say “we need some deferment my mother and I.” This brings to mind the epigraph of the book, by Alejandro Zambra, “But our parents never really have faces. We never learn to truly look at them.” A dislocation that’s an aspect of the way we see each other, maybe heightened in the way we see our parents because we tend to not see them but the roles they are playing. In any relation both aspects coexist: connection and dislocation, but I tend to place writing in the dislocation zone, since that’s where things, and the words to name them, might need to be put into motion.

Formally, fragmentation was also a way of exposing the holes/doubts/questions I have around the experience of being a mother, which—as any experience—is impossible to fully hear, see, grasp.

JDP: I think this is another one of the beautiful aspects of this book. You spend so much time thinking about your mother and your mother’s mother, while at the same time reckoning with your own motherhood. It reminds me of the final “scene” of the book, and I say “scene” because of the cinematic quality in the storytelling, these glimpses and glances, these long shots, this attention to looking. This figure of Mama—who is you and is not you and is your mother and is not your mother—arrives forcefully in the final poem in the book. How did this final poem arrive?

SLM: I like that you say “cinematic” because I worked on this book as if it were somehow a script, and I thought of its parts as “scenes.” This final poem-scene, which is the one that gives title to the book, was actually the first poem of the book that I wrote. I wanted to push the repetition of the word mama to see what could come from it, which in this poem is a multiplicity of mothers (my mother, her mother, myself, my paternal mother etc.). The word is the same, but what comes from it keeps changing, telling even contradictory things. In the end, isn’t that one of the words we move most around in our lives? Even after they die, it never dies.

And I wanted to explore the tendency toward trying to define a mother—“mama is this,” “mama does that”—something that not only we as daughters do, but that, as mothers, have to constantly take from others and even from ourselves. I was trying to expose some of the complications, contradictions, and also the tenderness, the mutual dependence that are part of the experience of being a mother.

JDP: As I was reading the book, I felt immersed in the feelings of longing and loss brought on by migration, and how these feelings become an inheritance passed from one generation to the next. Not only for you after moving to the States, but also for your mother as she moved to Argentina from Paraguay. In many ways the writing seems to grapple with the unsayable, with what is fragmented, with how to reconstruct a story that has been broken many times over. As you write, “is permanently reconstructing / sentences from fragments, isn’t that / writing?” Were you thinking about that idea of fragmentation as an inheritance of migration?

SLM: I think that writing is connected to dislocation, strangeness, some sort of lack of balance in things that make you want to name them. Or at least I don’t tend to write from a balanced, joyful experience. Also, one of my earliest memories about the act of writing are the letters between my mother (based in Argentina) and her mother in her home country (Paraguay). So, from the very beginning, writing was connected to being out of place. And changing perspectives. Letters are pieces of a life being told, which then my mother would literally turn into pieces, I say it in the book: she would read each letter once and then rip it into pieces. There must have been more than a hundred letters, and I wrote this book around the only two letters that she kept.

I’m not sure that I would have written this book if I were still living in Argentina. I needed the distance built through language to write this book, and I also needed the concrete physical distance. So maybe for this book at least, this dislocation was necessary, and the fragmentation that comes with it, the cracks that create distances and also open spaces.

JDP: Your attention to language and phrasing in the book is quite stunning. Really gorgeous. And this focus on how to say something feels meaningful. It turns our attention to the materiality of language—both written and spoken—especially as you grapple with the fact of deafness and partial deafness in your family. At one point, you write of your uncle, who was hard of hearing, that, “It was sometimes hard for us to understand, not him, but the words coming from him.” Do you think of this as an allegory? Are you pointing to broader issues of communication and miscommunication in language and in families?

SLM: I’ve always been interested in the physicality of writing. But before this book, I don’t think I had reflected on the relation between the material perception of words and the way of communicating with my family. My mother reads my lips, so from an early age I would emphasize the shape of words in my mouth for her (or my uncle) to understand me. So as I say in the book “words would become more material.” One of my preoccupations while working on this book was that it wasn’t only about my personal experience. I try to focus on what the text is doing on the language level, how the text might open, give space for the reader to enter, so that it somehow becomes a shared space. And I say space because that’s one of the things that interests me in writing, and when reading the works of others—even when staying within the page—the gesture toward turning the two dimensions of the page into a three-dimensional space.

And yes, I was thinking of broader issues of communication. This intermittent/fragmentary aspect is part of the way we all connect with each other, I guess it’s hard at times, and at times, also beautiful.