What’s in a name?

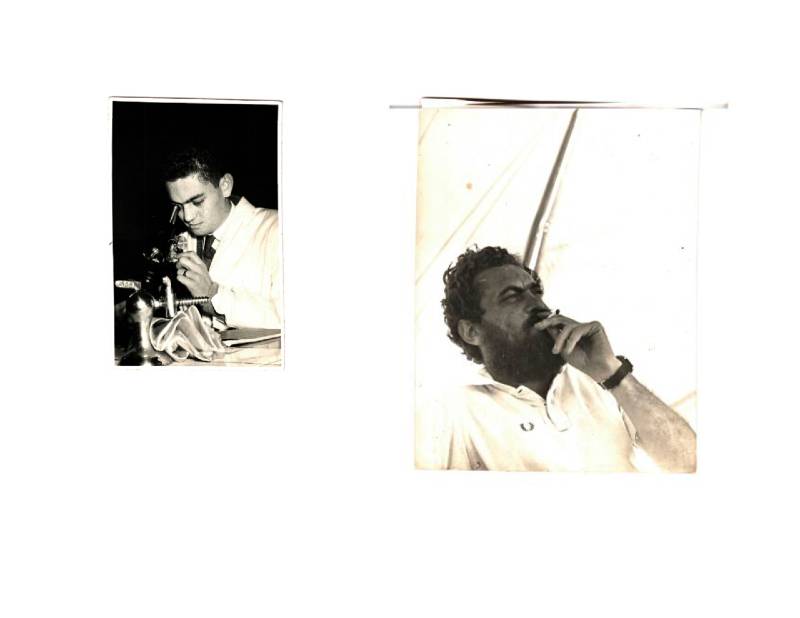

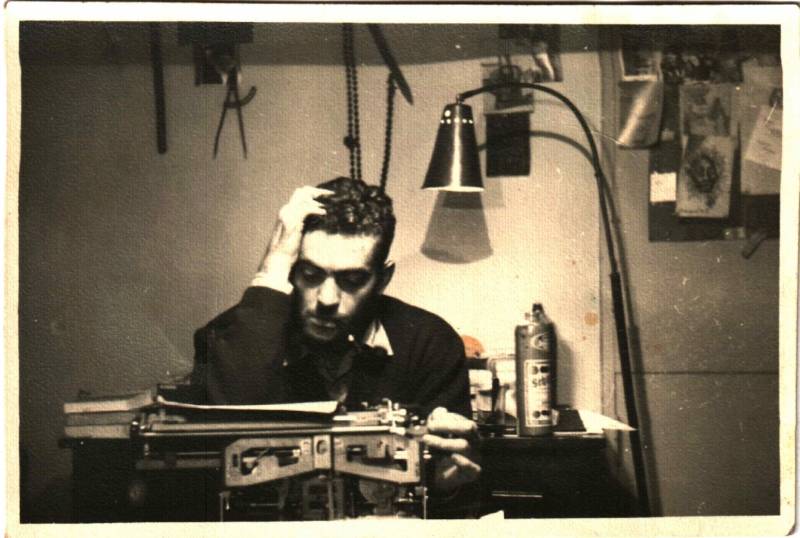

Most of the essays that make up this dossier refer to the name of Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill, one of Argentina’s most important authors of his generation, who passed away ten years ago. His friends used to call him “Quique.” Or “Kike,” as he preferred. Just “Fogwill,” as he became known. Fogwill as an adjective and a brand. Even his second middle name is mentioned: Samuel, after his father. These different names correspond to the many faces and lives of the author of the novel of the Malvinas/Falklands War Los pichiciegos; a man who was also so much more than that: a copywriter for chewing gum, an sailing enthusiast, a former medical student, a father, friend, critic, a “spoiled brat,” a “cultural provocateur, sociologist by trade, poet by revulsion, famous novelist by mistake,” and, according to Borges, the man who knew the most about both tobacco and cars. To commemorate the tenth anniversary of his passing, we celebrate all those men who made up Fogwill.

Two Archives

“It looked like a house on hold,” says Verónica Rossi, remembering the first time she visited Fogwill’s home after his death. Nothing had been moved: “There were plants, piles of papers, boxes filled with notebooks, magazines, and press cuttings, photos, ropes, dangling cables, parts for his yacht, as well as several dismantled computers strewn everywhere.” Courtesy of the author’s family, we include in this dossier many of the materials that make up the Fogwill archive: pictures, letters, postcards. Some others came from our contributors and their own archives.

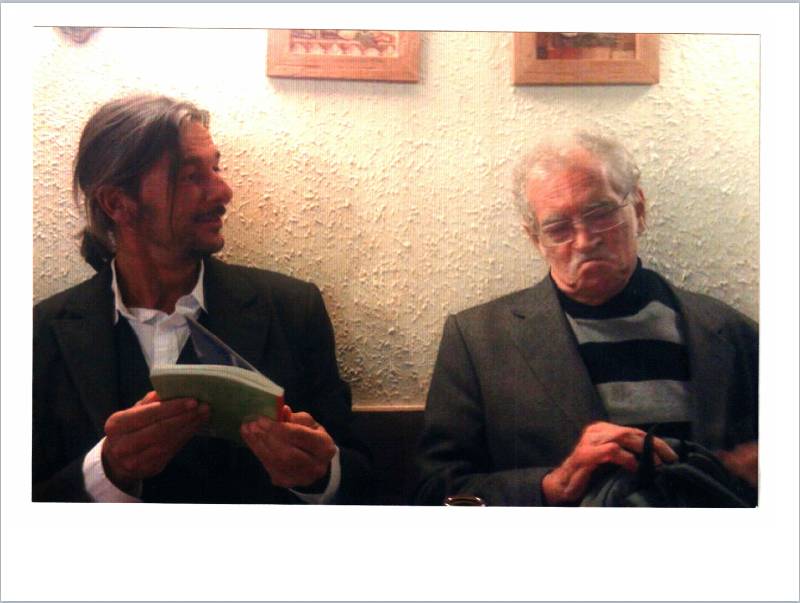

Because there is a second archive. The essays in this dossier also show the undeniable place Fogwill occupies in the Archive of Argentine literature and the personal archives of its writers. In his essay, Daniel Link says: “Yes, Fogwill is part of my archive, understood not as a dusty collection of old papers, but as that which defines my own conditions of enunciation (which is almost to say, my own conditions of existence).” Rodrigo Fresán regrets not having been included in his biography and mends the omission by offering his testimony. Roberto Brodsky remembers four encounters with the author. Francisco Garamona narrates the story of his library and of how Los libros de la Guerra came to be. It’s as if everyone has a Fogwill story to tell.

The Last Punk

“I write to avoid being written about,” he used to say. And, with this dossier, as Ana María Shua remarks in her essay, we betray him. We write about him and we remember him. We also hope to introduce him to our English-speaking readers, an audience who might still be unfamiliar with his work. Fogwill was translated into French, German, Croatian, and Mandarin. But in English, only Los pichiciegos was published in 2007, translated by Nick Caistor and Amanda Hopkinson and titled by its editors, despite the author’s wishes, Malvinas Requiem. We thus conclude this dossier with Fogwill’s story “Punk Girl,” translated by Will Vanderhyden; an Argentine classic never before published in English. This story is key because it would not only win the Coca-Cola Prize (and start the subsequent controversy many of our dossier contributors mention), but also open the door for the author’s literary career. We hope it becomes, for new readers, a gateway into Fogwill’s universe.

Visit our Bookshop page and support local bookstores.