When Roberto Bolaño won the Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize for The Savage Detectives, Hugo Chávez had only been in power for a few months. In those early days of his government, he broke with the tradition of Venezuelan presidents awarding the prize in person. He also said, at the time, with barely a few hours’ notice, that he would not be attending the ceremony because he had a fever. What’s true is that Chávez never attended any of the subsequent ceremonies for the Rómulo Gallegos prize, and a few years later he allowed the most prestigious literary honor in Latin America to become politicized.

Some previous fissure had given Bolaño reason to renounce being part of the judging panel for the next prize. Nonetheless, the decline was rooted in the speech given in 2003 by Fernando Vallejo, winner of the prize for his work El desbarrancadero, when, giving Chávez the perfect excuse, Vallejo criticized Simón Bolívar and donated his prize money to a humane society for animals. From then on, the Gallegos prize would be awarded to authors who aligned themselves with the ideals of the revolution.

By this I don’t mean that the novels that won prizes in the years to come were not good novels—that’s grist for a different mill—but that the prize was awarded to authors whose thinking was considered to be close to the ideals of the revolution, to the detriment of literary works that deserved to be awarded prizes.

When the prize, its prestige now tarnished, was awarded to Ricardo Piglia for his novel Blanco nocturno in 2011, one had the hope that the situation was starting to recover, but the joy was fleeting. To begin with, Chávez’s words on Twitter from the comfort and safety of his keyboard: “What a beautiful Argentine-Venezuelan event. Congratulations, compatriot Ricardo Piglia, for this well-deserved prize, the Rómulo Gallegos. Thank you!!!” We Venezuelans understand very well what this sort of praise from the commandant suggests, always thinking in terms of alliances and friendships, always administered with intentionality. Piglia, as well, would emit some controversial statements that were very badly received in the Venezuelan literary world.

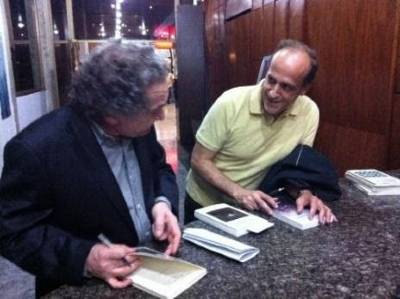

I happened to be in Caracas when the prize ceremony was happening. Along with a friend, a much bigger Piglia fan than I, we managed to insinuate ourselves into the event at the Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos Rómulo Gallegos (CELARG), in the same location where the writer and president of the country had his Caracas household, and where this headquarters was built. We managed to meet Piglia in a quiet moment before the ceremony, in front of the elevators. We spoke with him, he signed our books, and told us some stories about Princeton University. He struck me as humble and pleasant. Then we listened closely to his speech, seated among the back rows of the auditorium, sheltered by the darkness, outside the center of attention. As the applause died down, we slipped away into the shadows.

Many of the country’s best writers who had been in the running for the prize several years earlier, in 2009, asked their respective publishers to withdraw their books, in protest against the politicization of the prize. They also demonstrated publicly about this. The award’s disrepute increased in 2015 when Pablo Montoya’s prize money was significantly delayed, and then, the last straw, suspended indefinitely, claiming the State lacked sufficient financial resources.

Nor did the reactivated edition in 2020 enjoy the participation of recognized Venezuelan writers, due to all the problems and the economic penuries the country has been suffering from, consistent with its principles. That was not the case with a small number of celebrated foreign writers who aroused amazement and criticism in the local media, and who were, ultimately, not selected, not even as finalists—the only exception being Horacio Castellanos Moya. Let’s now consider the award we are most concerned with here: the winner of the prize in 1999 for The Savage Detectives.

From the start of what’s known as the Caracas Speech, Bolaño shows his literary prowess and ability with lucidity and a sense of humor. He begins with an anecdote about soccer, probably to loosen up the formalism of the ceremony. He talks about the problem he has with Venezuela and relates it to an undiagnosed dyslexia that he himself discovered when he played soccer and used his left leg. He relates it to writing: he was a left-footed shooter and a right-handed writer. Through verbal sleight of hand, he connects his dyslexia, his difficulty in situating the right side or the left side of the soccer field, with his difficulty in identifying the real capital of Venezuela. He declares that the most logical thing would be for Bogotá to be the capital of Venezuela and Caracas to be the capital of Colombia: the letter V at the start of Venezuela has a very similar pronunciation in Spanish to the sound of the letter B with which Bogotá begins, and the hard-C sound of Caracas is the same as the initial hard C of Colombia; he also says that Cantaclaro and Canaima, which he qualifies as the two best novels by Gallegos, apart from Doña Barbara, could be Colombian novels.

Then he alludes to an incident at a conference in Mexico, when he mixed up urban poets from Caracas with urban poets from Bogotá, and then he dives headlong into his word games. Bolaño goes deeper and comments that Doña Bárbara combines the sound of the B from Bárbara with the b-sounding V of Venezuela. Then he launches a direct allusion to Venezuelan idiosyncrasy: Bolívar and Bárbara, what a fine couple they would have made, he says, perhaps thinking about the strong and domineering character of the heroic liberator with a strong, dominant fictional character created by Rómulo Gallegos, who also coincides with the original title of this novel which, allegedly, Gallegos changed at the last moment: La coronela. At the heart of it, what Bolaño tries to sketch is that in the spurious years during which Bolívar’s dream was maintained, Colombia and Venezuela were one and the same country: La Gran Colombia. He skillfully Latinamericanizes his speech when he says that Bolívar died in Colombia, which is also both Chile and México, and he identifies the titles of works exchanged by Rómulo Gallegos, Vargas Llosa, and Carlos Fuentes. He even goes so far as to say that Pobre Negro is a Peruvian novel.

The speech, as it continued, caused joy among the listeners. From Arturo Gutiérrez Plaza, who at that time was the general director of CELARG and who had spent several days doing various things together with Bolaño, I have learned, thanks to various anecdotes he has told me about Bolaño’s one and only visit to Caracas, that Bolaño wrote the speech during those days in the Hotel Ávila, where the prize winners traditionally stayed. It’s a place surrounded by nature on the slopes of the imposing El Ávila mountain. Bolaño assured him that the powerful chirping of the crickets kept him awake all night; Vila-Matas, winner of the prize the following year, said the birds that sounded like car alarms kept him on edge; both writers were disconcerted by the cacophony of Caracas. Bolaño’s insomnia, along with the fever that his son Lautaro was suffering from, which required medical attention in Caracas and caused him great unease and anxiety, as Guitiérrez Plaza tells us, did not prevent him from composing a speech that was considered by those present to be intimate, affectionate, and very intelligent.

Bolaño returns to his initial wordplay about dyslexia and soccer; he affirms that he has just won the eleventh Rómulo Gallegos grand prize, Number 11, which was the same number on his team jersey when he played soccer, Number 11. Bolaño’s passion for soccer is manifest in his story “Buba,” dedicated to Juan Villoro, which takes place in Barcelona. He talks about coincidences, about the plaque for Rómulo Gallegos in Barcelona, on the building where he lived and worked. When Bolaño walked up to 11 Calle Muntaner, he discovered the plaque that, according to him, reads: “Here lived Rómulo Gallegos, novelist and politician, born in Caracas in 1884, and died in Caracas in 1969.”

That would make a triple coincidence: 11-11-11: jersey number 11, Gallegos living at 11 Calle Muntaner, and the eleventh annual Rómulo Gallegos prize. Bolaño uses so much humor—which suits him very well—to accentuate the coincidences a little bit more, he just happens to remember to tell everyone how, in his room at the Hotel Ávila, they’d left him a snack and a mysterious package of the extremely sweet Venezuelan cake known as Once Once—(i.e. “Eleven Eleven”), whose company’s factory was founded in Caracas by Don Rosendo Valentín Rondón Moronta on November 11 (i.e. 11/11), 1960, when Bolaño was seven years old.

Some inaccuracies take years to appear, without one seeking them out, and that is the case with the many coincidences in Roberto Bolaño’s Caracas Speech. A stroll along the streets of Barcelona in the year 2021 to visit the house of Rómulo Gallegos made me aware of the discrepancy between what is related and what is real, at least in what refers to a factual circumstance mentioned in the speech.

Bolaño’s translation of the plaque written in Catalan arouses the first suspicion: “Aquí visqué i escriví (1932-1933), Rómulo Gallegos, novelista eminent i President de la República de Veneçuela. Caracas 1884-1969.”1 In that sense, we emphasize the fact of the place of writing: Bolaño finds himself in Caracas, and he’s writing, grasping for what he remembers, through insomnia and the crickets in the background, and perhaps that explains why he relates so vaguely what’s written on the plaque. If we want to be precise, we would say that he fails to mention the years when Gallegos lived at that address; he invents the word “politician” and omits the adjective “eminent.”

The book Rómulo Gallegos y España (Caracas, Monte Ávila Editores, 1986) by José López Rueda contains some pages devoted to Gallegos’ life in Barcelona: “To help themselves financially, Gallegos and his wife took in three young Venezuelans as boarders: Simón Gómez Malaret, Nelson Himiob, and Jesús Lavié… and sometimes Gallegos’ apartment would be visited by young fellows who didn’t live in Barcelona, like Gonzalo Barrios, Miguel Otero Silva, or illustrious Venezuelans like Pedro Emilio Coll.”

Here arises a second, more concrete, suspicious point. What I mention next, I confirmed by walking from the address where Bolaño lived in Barcelona, Carrer dels Tallers 45, to Calle Muntaner 11. This route takes only about five to seven minutes on foot and doesn’t really seem like the exhausting Ensanche district he mentions in his speech. Although, geographically, this spot marks the edge between the Ensanche and Barcelona’s old city, it’s not an area of especially wide streets, which is how Bolaño describes the area where he found himself when he discovered the plaque. Even more significant is the distance to the house where Gallegos really lived, just short of a mile away, about twenty minutes of fast walking amid the summer heat; which makes it improbable that he would have been confused about it, even with the way the mind plays tricks on our memory.

The speech continues, and Bolaño speaks about writers and their native lands: their language, the people they love, their memory, loyalty, and valor. The home country can be simply the novel that is written at a particular moment in time. The passport to those countries of literature is the method of writing––not just writing well but writing marvelously well. “It seems to me now that there can be many homelands, but only one passport, and that passport, evidently, relates to the quality of the writing.” What makes good writing? Bolaño answers his own question: “Knowing how to stick your head into the darkness, knowing how to leap into the void, knowing that literature is basically a dangerous job.”

A dangerous calling, indeed, and for many reasons, including when a writer, either voluntarily or involuntarily, alters concrete reality in order to make it match their story, be it fiction or nonfiction. And I don’t say this in a spirit of judgement—I’m not judging because I don’t consider anybody to be the owner or master of the truth. I’m only sharing my own take, without trying to seem grave or affected—a deplorable attitude—nor for any excessive love of formalism, which limits creative freedom, while maintaining my admiration for the Chilean novelist.

Sometimes one reads a text and misses details along the way, unable to assimilate so many different things the first time. I’d had a few chances to visit the building where Gallegos had lived, and I knew it couldn’t be at Calle Muntaner 11. Nevertheless, thanks to my cluelessness, that missing piece remained isolated in a mental fog, as if due to a small taste of what supposedly happens in Colombia or Venezuela—with, to paraphrase Bolaño, their interchanged capitals—when some criminals spike people’s beverages with scopolamine, also known as Devil’s Breath, and in Spanish burundanga, spelled with the B of Bogotá, Barcelona, and Bolaño: the person’s judgement and memory turn cloudy, and unspeakable things happen. Like an aftereffect of the Caracas Speech, Venezuelan writers residing in Barcelona frequently ask: “Hey, man, where the hell is that Rómulo Gallegos plaque? I’ve never been able to find it. I always get mixed up, I walk all around till my head spins but I can’t ever find it,” as if they were talking about some hidden location requiring a secret initiation ritual to gain entrance.

What’s more, Bolaño ran a serious risk during his speech because, if someone in the audience had known the real address of Gallegos’ house in Barcelona, and had stood up, as abrupt, spontaneous, and direct as we Venezuelans are, he could have called him out or questioned him right inside the auditorium:

“Hey, listen Bolaño, with all due respect, you’re wrong: Gallegos’ house is located at Muntaner 193.”

And it’s now when I realize, after paying homage to the Venezuelan novelist in May 2021, upon returning to Barcelona after unexpectedly staying in Caracas for a whole year, trapped by the pandemic, the discrepancy that was floating in my head as if in the zero gravity of space. Gallegos, clearly, had not lived at 11 Calle Muntaner but at 193 Calle Muntaner, where he had written, concluded, and then submitted his novel Cantaclaro to the publisher Araluce.

The mind comes floating back down to earth.

Bolaño also says that Number 11 corresponds to one of the “two different houses” of Gallegos in Barcelona, and says that Pere Gimferrer, whom he uses as a shield, told him that Gallegos had two houses, when all sources indicate that Gallegos lived only at one address in Barcelona, Besides, there is no doubt that only one single plaque exists. This is confirmed by Xavi Ayen in his book Aquellos años del Boom. Offering a detailed discussion of Gallegos as a precursor to this movement, Ayen affirms: “Who knows if he came attracted by the sonority of a name that evoked for him his brief stay in the Venezuelan Barcelona, where he directed the Colegio Federal de Varones (Federal Men’s College) and married Teotiste Arocha in 1912. He worked as sales manager for the National Cash Register Company, and in his flat at Calle Muntaner 193, a plaque in Catalan commemorates his stay. There he conspired politically with the tranquility afforded him by the protective barrier of the ocean.”

Gimferrer and Bolaño enjoyed a close relationship. To begin with, it seems to be what enabled Bolaño to become known in Spain. In a conversation published by the Nueva Revista in June 2017, Gimferrer affirms: “I did not discover Bolaño in the strict sense of the word, because he’d already published work, only nobody was paying any attention to him. Then he sent [me] the manuscript of Nazi Literature in America and I proposed publishing it; and so it was done, and the book signified his launch as an author.” But more than this anecdote about Bolaño’s literary launch, the speech’s explicative tone, along with its playful and transgressive spirit, reflect both men’s way of viewing the writerly life. In the prologue to Bolaño’s The Romantic Dogs (Barcelona, Acantilado, 2010), Pere Gimferrer writes: “His fictions, in some way realistic except as metaphor and parody, not only of reality, but of themselves, in the fecund ambiguous frontier in which pastiche and homage adjoin, are just as poetic as his poems/anti-poems are narrative.”

For his part, Bolaño signals his admiration for Gimferrer in multiple interviews. For example, in some statements made to the Mexican media upon winning the Rómulo Gallegos prize, he comments: “Pere Gimferrer has lucid texts on this point. A writer should never pursue respectability: it’s completely contrary to any literary project because it tends toward immobility, toward consensus, toward the approval of others and a secure position in society. They should not seek any position in society, they should flee from it, from any position. They should walk freely through the open air and let the elements be their household. The first thing necessary to consider is that they should destroy figures on the landscape and not wink at power, whatever that happens to be, on the left or on the right… Power is always an obstacle between the writer and the elements where he lives.”

In this sense, it’s worth highlighting, like an affinity between Bolaño and Gallegos, what José López Rueda tells us: “It’s well known that Rómulo Gallegos eschewed literary salons and conversations. For that reason, despite the fact that his novels sold quite well in Spain, he was not very well known in literary circles.” Being a Latin American writer in Spain, his work would be spread, in a rather uncommon way for the time, given Spanish readers’ preference for authors from their own country, when the Spanish Association of the Best Book of the Month chose Doña Bárbara as its selection for September 1929. Even so, Gallegos did not mingle much with the media, perhaps in agreement with what Bolaño affirms: “A writer should never pursue respectability: it’s completely contrary to any literary project because it tends toward immobility, toward consensus, to a vote from others, and to a place in a society.” Which means, returning to the sense of the speech, is that it could be interpreted as a grand parody, and it’s possible, I’d venture, that Gimferrer and Bolaño shared a good laugh together over their roguish farce about Gallegos having two different houses in Barcelona,

Bolaño’s speech has also had its practical repercussions over time. Apart from the various lost Venezuelan writers spinning around like a child’s top looking for the Gallegos plaque, I find, for example, a literary blog from 2006 whose author, who claims to write “reckless reviews of the books that fall into my hands,” as a result of the Caracas Speech, comments: “Reading that Bolaño knew that Rómulo Gallegos lived in Barcelona: he had seen a plaque like the one he mentions in the entry. All my attempts to locate this aforementioned plaque were in vain. Not even Google knew the answer.” Nowadays, clearly, you can definitely find the street address, but perhaps not back in 2006. Those who took the Caracas Speech seriously, even knowing it to be a literary piece filled with roguishness and humor, were never able to find Gallegos’ house in Barcelona.

At the end of the prize ceremony, Bolaño spent several hours signing his books and talking, especially with young people. He was generous and open with the people, generously making time for anyone who brought him one of his books to sign. This was possible through an initiative organized by the CELARG administration that year. As one of the conditions for the award, Monte Ávila Editores had the right, for the first time in the prize’s history, of bringing out a Venezuelan edition of the winning novel, whose price would be affordable for Venezuela’s general public and especially for the young people to whom Bolaño dedicated so much time.

In other countries, most award committees, throughout the history of literary prizes, choose as many as half of their winners from the native-born population. Not so with the Rómulo Gallegos prize. To date, only a single Venezuelan writer has won it: Arturo Uslar Pietri, for his novel La visita en el tiempo. In the interest of a supposedly misunderstood impartiality, the various juries never chose Venezuelan writers who might have deserved it. The winner walked away with a significant monetary prize, the big Spanish-language publishers benefited from increased sales, and the country got nothing. Just like that, in the interest of achieving a balance between what’s given and what’s received, this condition was imposed, and saw its debut, precisely, with The Savage Detectives. Bolaño was the first honoree to enjoy the privilege of a guaranteed Venezuelan edition of his prize-winning novel, and he was able to see, in situ, in a nighttime visit to the old headquarters of Monte Ávila Editores in the La Castellana neighborhood, in the company of Gutiérrez Plaza, the offices where numerous people worked on the process of digitization, correction, editing, layout, and printing his novel, a few days before the prize ceremony. At that time, Alexis Márquez Rodríguez, who publicly supported this initiative with great enthusiasm, was the president of Monte Ávila, in its time one of the large publishers with widespread market coverage in Latin America and Spain.

Literary talent—which Bolaño, with his undisputed obsessive dedication, had in abundance—translates, in the act of writing, into blood, sweat, and tears. Along that path, it’s inconvenient to alter tangible, concrete, and provable realities. I cannot say that Spain lies north of Europe, nor that Chile shares a border with Colombia or that Liechtenstein and Andorra are neighbors, nor that Bolaño lived in one of the buildings on the Rambla del Raval, right smack in front of Botero’s enormous cat, set there after being dragged from the Ciutadella Park, through a plaza in Drassanes and the Olympic Stadium. Of course I’m taking my examples to the extreme, but, what if someone composes a text with one of these premises? Not for nothing the final word of Bolaño’s speech: “Pinocchio.”

In all likelihood, Bolaño was conscious of his own game when he affirmed: “By this point in the speech, I hope that Don Rómulo is not too angry at me; I also hope he doesn’t decide to haunt the dreams of Domingo Miliani,” this last comment an allusion to the founder of the CELARG and the institution’s president at the time. Bolaño had become very fond of him during his stay in Venezuela, along with various members of that institution who hosted and attended to him during those days, with whom he later maintained an affectionate friendship. This lasted until the lamentable impasse in 2001, when Bolaño declined to serve as a jury member for the twelfth edition of the prize, motivated by, among other things, the unfortunate declarations of the next president of CELARG during the Chávez era, the sociologist and philosopher Rigoberto Lanz. A week after the verdict, Lanz declared that “the Rómulo Gallegos prize smells fishy,” saying that it had a corrupt history. Such infamous and irresponsible statements kept the prize from being awarded that year. The successful handling of the situation, on the part of the four other remaining jurors, Sergio Ramírez, Victoria de Stefano, Carmen Ruiz Barrionuevo, and Edgardo Rodríguez Julia, enabled it to weather the storm.

And with the nostalgia induced by the title of his story “Last Evenings on Earth,” how could Bolaño have imagined that everything was going to accelerate beyond expectation, that three years after his Caracas Speech he would die, and that he too would then have a plaque in the place where he lived in Barcelona, in the Raval district, Carrer dels Tallers 45, in a flat measuring twenty-five square meters, before moving to Girona and then isolating himself in the coastal city of Blanes. The plaque, translated from the Catalan, says: In this house lived the writer and poet Roberto Bolaño Ávalos. Santiago de Chile 1953 – Barcelona 2003. Barcelona with B for Bolaño, the same where he wrote—so they say—his poem “The Romantic Dogs,” which begins like this:

At that time, I was twenty years old

And I was crazy.

I’d lost a country

but I had gained a dream.

And as long as I had that dream

nothing else really mattered.

Translated by Brendan Riley

1 Translated from the Catalan: “Here lived and wrote (1932-1933) Rómulo Gallegos, eminent novelist and President of the Republic of Venezuela. Caracas 1884-1969.”