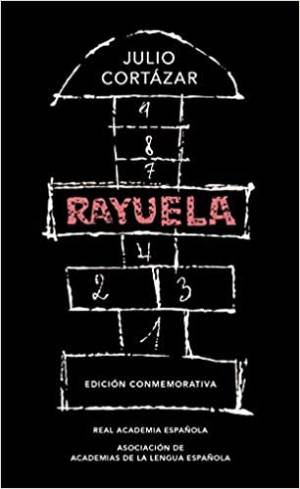

Rayuela – Edición conmemorativa. Julio Cortázar. Barcelona: Alfaguara/Real Academia de la Lengua/Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española, 2019. 1,026 pages.

Some fifty years after its appearance on the literary scene, we could venture to ask whether the novel Rayuela has aged well; if, indeed, it is a classic of today’s Latin American literature. Different readers have different opinions. In fact, there are those who say that Julio Cortázar’s best writing isn’t found in his emblematic novel, but rather in his notable works of short fiction. Nonetheless, the Real Academia Española and the Asociación de la Lengua Española’s decision to include this title in their exclusive collection of commemorative editions—which includes works by Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes and Augusto Roa Bastos, as well as collections of works by Jorge Luis Borges, Rubén Darío, Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral—seems to suggest that Rayuela certainly is one of Latin American literature’s canonical works.

Some fifty years after its appearance on the literary scene, we could venture to ask whether the novel Rayuela has aged well; if, indeed, it is a classic of today’s Latin American literature. Different readers have different opinions. In fact, there are those who say that Julio Cortázar’s best writing isn’t found in his emblematic novel, but rather in his notable works of short fiction. Nonetheless, the Real Academia Española and the Asociación de la Lengua Española’s decision to include this title in their exclusive collection of commemorative editions—which includes works by Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes and Augusto Roa Bastos, as well as collections of works by Jorge Luis Borges, Rubén Darío, Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral—seems to suggest that Rayuela certainly is one of Latin American literature’s canonical works.

Regardless of how we look at it, Rayuela certainly marked an entire era of the Latin American novel, which in the 1960s was just beginning to be written. Critics of that time saw in Rayuela a new form for representing reality and, above all, a new means of understanding the art of the novel. Because of this, Cortázar’s novel was quickly classified in many ways: a great anti-novel (heir of the finest avant-garde spirit), a vast collage composed of many fragments, a parody of genre, a story about impossible love, a search for existential transcendence, among many other possibilities. The story of Horacio Oliveira very quickly became a touchstone for writers of the Boom generation, as it spoke to their renovating spirit and their desires to experiment. Rayuela is faithful to the winds of change of the turbulent 1960s and it seems to question everything: life, love, culture, and, more precisely, the very act of reading. All of this emerges from writing that takes risks and freely creates an alternative reality, a world without tethers that fosters its protagonists’ metaphysical pursuits and that makes human existence a more tolerable, less routine adventure. The query opening the novel—“Would I find La Maga?”—is truly an essential question, as Oliveira and La Maga are lovers who never arrange a date: rather, they are two people always playing with chance encounters, as well as missed meetings; in other words, with love and heartbreak. Read carefully, Rayuela is one big game of improvisation and creation, like jazz—an artform Cortázar greatly admired. It is a mode of narrating in which his agile prose is nourished by the ebb and flow, the impulse of the moment but, above all, by the search for the most genuine expression of his characters’ inner worlds.

This spirit of improvisation and play is already clear in the novel’s “Table of Instructions.” Here we are told, “In its own way, this book consists of many books, but two books above all” (English versions are from Gregory Rabassa’s 1966 translation, Hopscotch). For this reason, the author suggests we read his story several ways: from the beginning to chapter 56, leaving the rest of the book aside; or starting with chapter 73 and following the order noted at the end of each chapter until reaching the book’s last page. This second option means the reader must jump from one place to another, like playing hopscotch. Therefore, with the help of an “accomplice reader” willing to follow these instructions, the novel has multiple possible readings. Nonetheless, if we pick the second option, we quickly figure out that the purported last chapter is chapter 131, but that chapter sends us back to chapter 58, and 58 sends us once again to 131, which makes reading the text an infinite endeavor. But if Rayuela proposes a reading rooted in chance, it also casts doubt upon the traditional structure of the novel. At the beginning, the story seems to have a three-part structure: a first part titled “From the Other Side,” which takes place in Paris; the second part, “From this Side,” which occurs primarily in Buenos Aires; and the so-called “From Diverse Sides,” which, according to the author, the reader need not read at all, thereby turning the three parts of the novel into two parts. This structure suggests a voyage: a continuous and improvised journey that the protagonists will embark on again as soon as they finish the journey prior. This all leads to the goal of landing on “home” in the game of hopscotch (but not without also landing on the Zen Buddhist “absolute center” or the Hindu mandala).

This new edition of Rayuela is, without a doubt, a luxury edition. First, it brings together texts by some of the writers who travelled alongside Cortázar in his literary journey: Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Carlos Fuentes, and Sergio Ramírez. All these writers reflect on Cortázar’s life and work, as well as the personal relationship they shared with him. The novel’s original cover is reproduced, along with the 699 pages of the first edition from June 1963, which was published in Buenos Aires by Editorial Sudamericana. Additionally, the facsimile reproduction of Cortázar’s Cuaderno de bitácora and its respective transcription are also included. First published in 1983 by Ana María Barrenechea, this logbook gives us a close look at Cortázar’s ambitious creative process for writing such a complicated text. Moreover, Julio Ortega, Andrés Amorós, Eduardo Romano, and Graciela Montaldo include an extensive bio-bibliography of the author, which helps us understand his life’s path in detail, as well as the progression of his entire body of work until his death in 1984. The book closes with a critical bibliography on Rayuela, a glossary and an extensive onomastic index.

The many documents, bits of information and critical readings included in this thick volume show that there is a Rayuela for every reader. The name of the novel alone evokes innumerable images and sensations for readers: the idea of a journey of initiation, the beginning of adulthood, jazz, marijuana, exile, Parisian bohemia, the essential nature of love and sex, and the search for spiritual balance, among many other themes. This entire vast universe meets the reader with a language that is always daring and audacious: Cortázar’s own language, where everything is a game.

César Ferreira

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Translated by Amy Olen

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

César Ferreira is Professor of Spanish at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He is a member of the Academia Peruana de las Letras and serves on the editorial board of World Literature Today. His most recent publication is the volume Narrar lo invisible: aproximaciones al mundo literario de Sara Mesa (2020). In January 2020 he received an Honoris Causa from the Universidad Ricardo Palma in Peru.

Amy Olen is Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her Ph.D. is in Spanish and Portuguese from The University of Texas at Austin. She holds Master’s Degrees in Translation Studies and Spanish and Portuguese, both from UW-Milwaukee. Her research interests include Latin American Indigenous writing and Translation Studies.