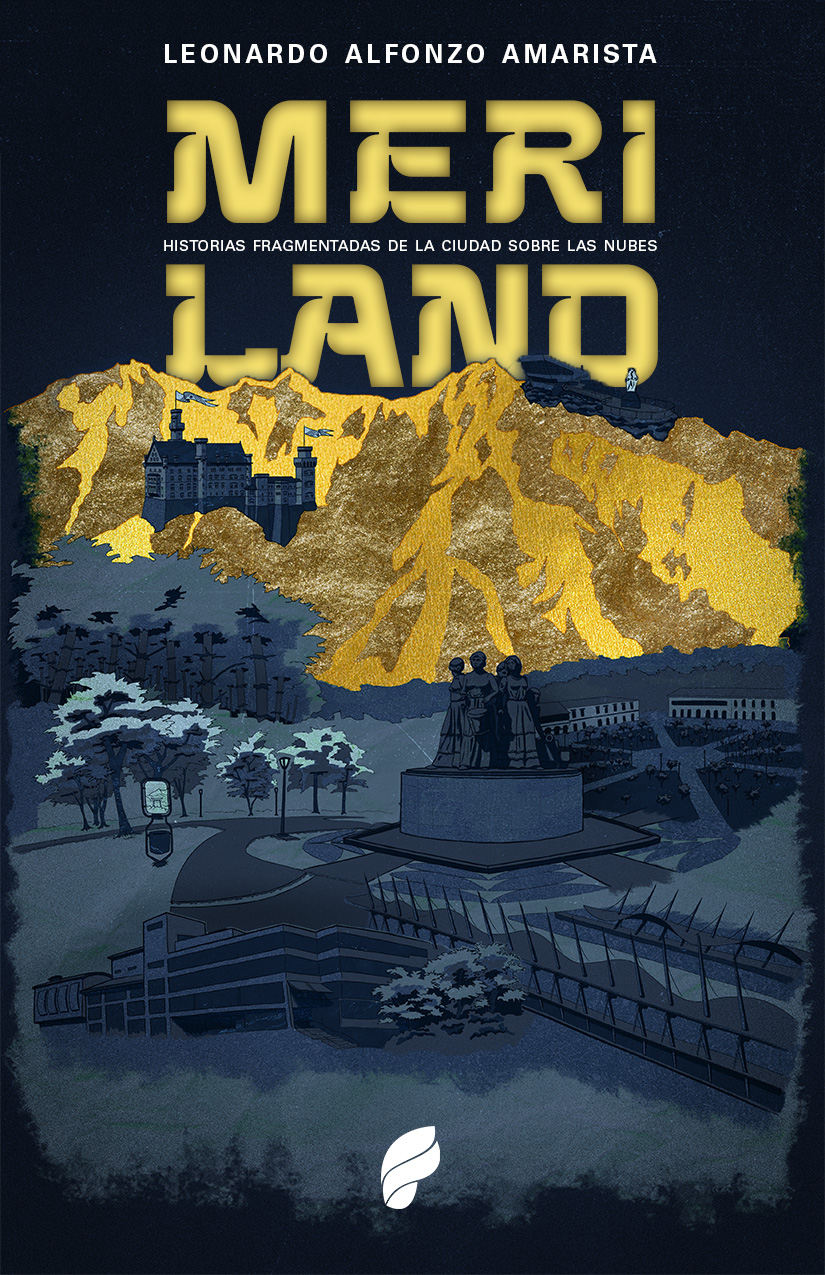

Venezuela: Ediciones Palíndromus. 2023. 86 pages.

A nostalgia-flavored tea: that’s the line that came to mind when I read Meriland. Maybe it sprouted up from the warm ecosystem of these stories and poems, for this book by Leonardo Alfonzo Amarista, a Venezuelan writer of poetry and prose based in Buenos Aires, seems to be underpinned by a ritual: letting scenes and memories flow. The images we glimpse, the tribute to spatial elements (city, nature, dimensions) are in dialogue with his two prior poetry collections, Jardín Okigata (Alción Editora, 2021) and Días de chanza (Luba Ediciones, 2023), weaving together, poetically, a journey.

A nostalgia-flavored tea: that’s the line that came to mind when I read Meriland. Maybe it sprouted up from the warm ecosystem of these stories and poems, for this book by Leonardo Alfonzo Amarista, a Venezuelan writer of poetry and prose based in Buenos Aires, seems to be underpinned by a ritual: letting scenes and memories flow. The images we glimpse, the tribute to spatial elements (city, nature, dimensions) are in dialogue with his two prior poetry collections, Jardín Okigata (Alción Editora, 2021) and Días de chanza (Luba Ediciones, 2023), weaving together, poetically, a journey.

The title serves as another substantial clue, as it reveals the material the author uses to weave together his discourse’s meaning: Historias fragmentadas de la ciudad sobre las nubes, we read, or “fragmented stories of the city over the clouds.” We ought then think of a place, of the tuning of memory, of sounding out everyday, intimate moments of college students getting by in a city that, seen in perspective, offers up its favors, its warm and magical spaces. Days, evenings, and nights rich with the freshest, most inspiring kind of friendship. Bonds secured by the orality of these events, anecdotes of mischief and the vibration of bodies united. Individuals who bear, in the first place, the feeling of having left behind their home territories to study in another part of the country: Mérida. The thread of migration and the growing Venezuelan crisis form part of the context.

The Universidad de Los Andes, the city’s Plaza Bolívar, its student accommodations, streets, and mountains make up the narrator’s commonplace journey, the map. The line we read in this book’s unconventional index—“You are here. Choose your own path to get to know Meriland”—is not gratuitous. It is a proposal of choice and adventure, offered to the reader. In the background, an illustration of mountains. Experience is transmitted through the discourse’s layout. The speaker speaks from an experienced, sometimes solitary “I,” but also from a “we”—that is to say, from other voices that root down the anecdotal nature of the scenes, even inscribed in fragments: quotes, songs, poems, conversations.

“Meriland achieves a balanced blend of imagination and memory. It shows the city with the frequency of a jaunt, its enigmas and spaces where all times flow together, indexed on packs of cigarettes”

There are three stories in particular—“I,” “II,” and “III Desdoblamiento”—whose scenarios border on the filmic, without losing the aura of memory. In “I,” the perspective presents us with a character, a building (a castle), and a party. A group of young people in costume take on protocols and verbal transactions as levels. The narrator, also costumed, greets, observes, and weighs up the place. The story develops as if shot-by-shot: “I must admit, I felt like I was in a Tarantino movie, right in one of those scenes that breaks the tension and seriousness.” The reader follows a character as they enter the venue and knows their thoughts, their eagerness to uncover (and recognize) faces, perceiving scents, textures, trances; spaces and light: “There were about fifteen of us in a massively wide rectangular room, with enough light for everything to show off its corresponding name.” Consequently, you bear witness, among other aspects, to the intimate and mortal act of finding out you’re in a game, and taking it seriously.

In “II,” the act of seeing—and its varying degrees—takes on new meaning: “Few people manage to see most of the elements that make up a given space; there is something routine to looking only down and forward when you walk,” the narrator observes. The verbs “to see,” “to notice,” and “to detail,” and the expression “shine a spotlight,” lend nuance to the act of contemplating surroundings and objects as a ritual happening or creative occasion. In this story, we read a reflection on the current state of language: uses, changes, twists. This brings us back to the party (the game), the tradition: the concave of academics who throw down their cards. Something is moving inside Meriland’s locations, and it is up to us to discover it.

“III Desdoblamiento” accentuates the book’s reflection on a field of inventions: “Sometimes I practice word games and I make up, for my friends and me, as a joke, a resemanticized space. I suppose it’s the new memory exercise I’ve picked up.” The characters are constructed with and through the language of intimacy: they open up (or create) their own dimensions, their own codes, even more so when writing is the art that goes along with them. Fiction plays its turn: the “I,” without leaving its solitude behind, comes up against another: “It’s 3:00pm and Adelfuns sits down beside me, with no prior warning. His presence is pleasant. His eyes are calm and sometimes he looks sleepy […].”

Meriland achieves a balanced blend of imagination and memory. It shows the city with the frequency of a jaunt, its enigmas and spaces where all times flow together, indexed on packs of cigarettes. Its poetry lies not only in the section “Poesía testigo,” as another anecdote, but also in the storyteller’s vision, in the setting’s behavior. Similarly, we must take heed of the writer’s fondness for the cultural production of the Far East—manga, anime—to which the book alludes. These narrations come together into a repertoire of noble intent: brotherhood. They contain presences and a country-cum-wound. They are stories written by someone who has become a foreigner.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon