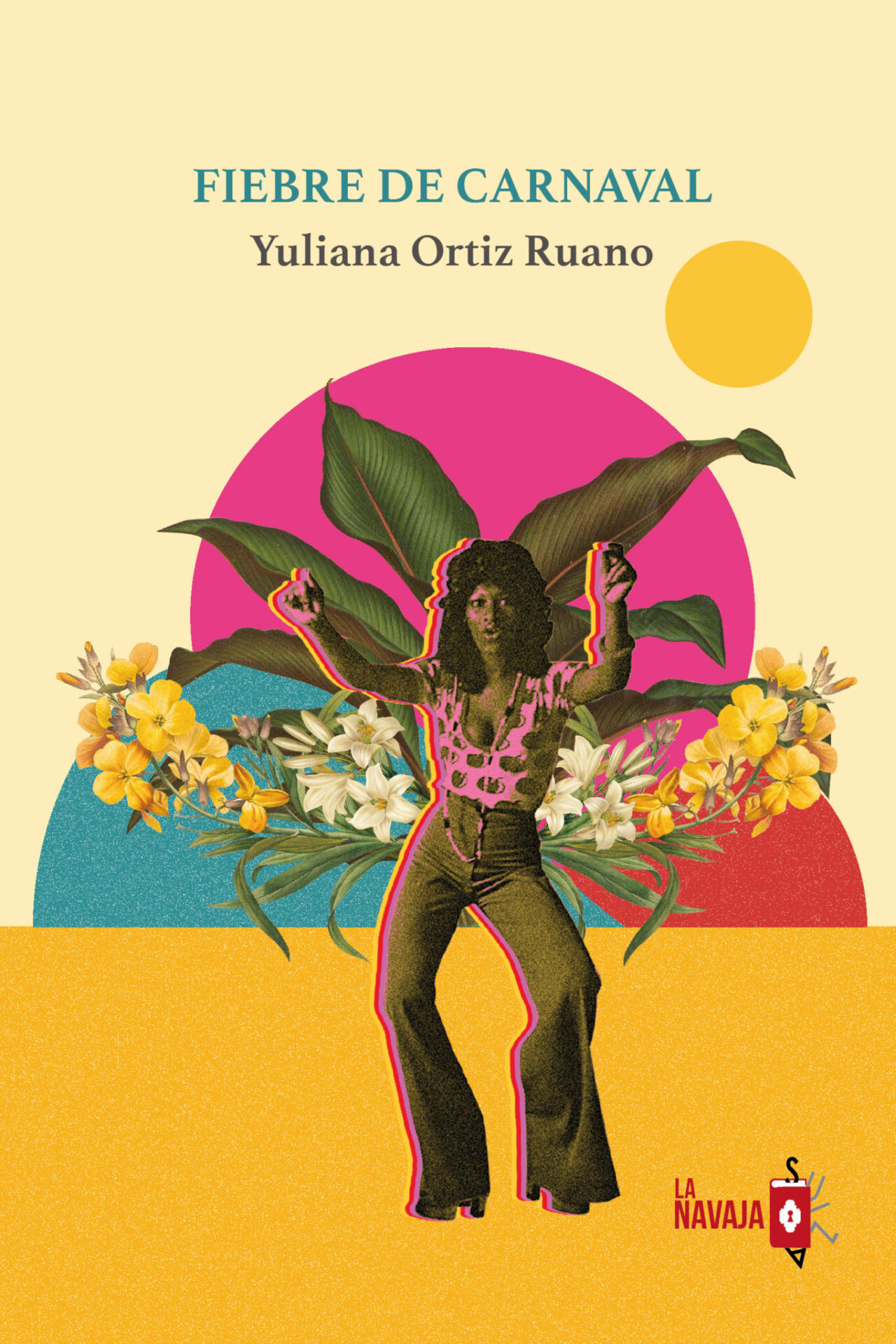

Madrid: La Navaja Suiza. 2022. 176 pages.

Remarkable Ecuadorian writer Yuliana Ortiz Ruano stands out for her ability to write with both hands: the fictional and the poetic. As far as poetry goes, she has published Sovoz (2016), Canciones desde el fin del mundo (2018), and Cuaderno del imposible regreso a Pangea (2021). As a fiction writer, she has penned the novel Fiebre de carnaval (La Navaja Suiza, 2022) and the book of short stories Litorales (2023). Her first novel has earned her important literary recognitions, such as the Premio IESS a la Ópera Prima in Italy and the Premio Joaquín Gallegos Lara, awarded by the city of Quito to the best novel of the year.

Remarkable Ecuadorian writer Yuliana Ortiz Ruano stands out for her ability to write with both hands: the fictional and the poetic. As far as poetry goes, she has published Sovoz (2016), Canciones desde el fin del mundo (2018), and Cuaderno del imposible regreso a Pangea (2021). As a fiction writer, she has penned the novel Fiebre de carnaval (La Navaja Suiza, 2022) and the book of short stories Litorales (2023). Her first novel has earned her important literary recognitions, such as the Premio IESS a la Ópera Prima in Italy and the Premio Joaquín Gallegos Lara, awarded by the city of Quito to the best novel of the year.

Fiebre de carnaval (translated as Carnival Fever by Madeleine Arenivar, and as-yet unpublished in English) tells the story of Ainhoa, an eight-year-old girl who lives in Esmeraldas, Ecuador. She tells of her experiences herself. On some pages, her voice is marked by great lyricism, sometimes in verse and at other times in prose—evincing the author’s double-handed writing style—but with strikingly intense images in both kinds of discourse. Ortiz Ruano’s bipartite talent flows through an element that is present throughout the novel: music.

This is a book that pays homage to dance, to Latin American culture, to African roots. This is a novel that moves its feet, marked by the joy we find in some of its characters. Ainhoa tells, from a not-so-innocent perspective, the story of her family, her relationship with her ñañas (her mother, grandmother, and aunts), the ever-present gaze of Mamá Doma, whose portrait in the living room might as well be that of an ancestral myth, her thoughts and fancies set to the rhythm of Los Van Van, champeta, and cumbia.

As time goes on, Ainhoa discovers a world that leaves room for tenderness, but is usually brutal. You get the impression that her surroundings mean to force her to grow up, to enter into a sort of premature adulthood through advice she does not entirely understand. She seems to have little interest in doing so. That’s why she climbs up a guava tree and, from the top, talks about what’s going on with her, what she’s feeling, what she’s thinking. Trees, water, nature in general are the spaces where this protagonist feels safe and can be herself without fear of reproach.

“Fiebre de carnaval is a book that can be read as the construction of a Latin party soundtrack, both to set the scene for rejoicing and to add some spice to injustice”

Esmeraldas in a place where carnival springs eternal. To explore it through this novel is like strolling through any Caribbean neighborhood. You can hear the music blasting at max volume from some neighbor’s speaker (hanging from the window or door of his house); the elders sitting on the sidewalk, smoking their tobacco and drinking their aguardiente while they spin some yarn; the people dancing and wearing out their shoes on steeply sloping alleyways. You can feel the hustle and bustle. Fiebre de carnaval is rhythm and sweat turned into words. Reading this novel is like walking into the middle of a party.

Ainhoa is part of this somewhat baffling carnival. A carnival that’s taking place in Esmeraldas, but that could be in any poor, Latino corner of the world. In a flash, she watches scenes of adults who want to rob her of her innocence. She is blown away, walking down the street amid drunks and thunderous music. She is a little girl who wants to continue being just that in an environment that seems to warn her of its dangers; a place full of “fits of tears on dancing feet […]. Melancholy to a drumbeat.” Such is the fever in this town: pleasure and energy boil over at every corner, though a select few don’t feel they are part of it.

With great narrative skill, Ortiz Ruano shows us a girl who questions everything from a perspective that is childish and exacting all at once. The novel is the product of a biting language that is all her own. A vocabulary that, while being that of a child protagonist, is full of rawness. Ainhoa has no qualms about expressing why she must be deprived of certain things out of the fear they have instilled in her, as if she were marked from birth by something she knows not (something called “racism,” a word that, at eight years old, she has not yet discovered):

My Mami Nela’s house is halfway between two barrios, serious stuff […], a little line that splits the good from the bad. A babygirl, ain’t nothing you need to be doing up there […]. And I always wanted to know why when we’re so close. We’re the good guys, seems like, and the ones on the left and on the right up there are the bad guys.

Very much in the style of Junot Díaz (who welcomes readers to this story with an epigraph), Ainhoa is a character who represents that spirit of Caribbean girlhood who wants to strip everything bare with her eyes, to know more about her own culture and understand those things that happen on the outside and end up affecting those least responsible for them:

Crisis and the kids […] left behind by their dads who left, maybe to Chile or the United States […]. Holiday, but here there’s no happiness or festival, just dead people on the radio […], there are lines to buy milk, lines to buy bread, lines outside the banks, tires on fire inside the banks […]. The streets are a photograph burning up forever.

And, even with some streets set alight with rage, there are always other streets lit up by revelry. That’s why Fiebre de carnaval is a book that can be read as the construction of a Latin party soundtrack, both to set the scene for rejoicing and to add some spice to injustice. There’s plenty to celebrate, it’s true, but also plenty of social critique between the lines.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon