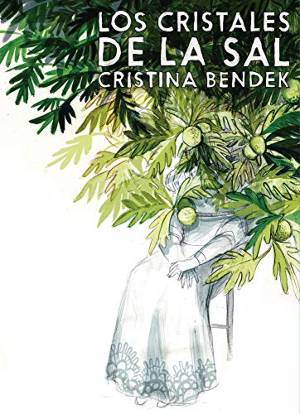

Los cristales de la sal. Cristina Bendek. Bogotá: Laguna Libros. 2018. 248 pages.

Homecoming. Returning to what was once familiar. After years of living abroad, Veronica Baruq returns to her home island of San Andrés, in the Colombian Caribbean, where so much, and yet so little, has changed. For a start, Veronica seems to understand that her relationship with the island, something that used to be so familiar, is now something altogether different, and with that readers witness a rediscovery of the island—and by extension the Caribbean itself—through the eyes and experience of a young chronicler who is neither from here nor there: she is an islander accustomed to life in the big city; a native with Raizal blood, but also Irish, Scottish, and Jamaican blood, blood from the island of San Andrés and from the continent, all coursing through her veins.

Homecoming. Returning to what was once familiar. After years of living abroad, Veronica Baruq returns to her home island of San Andrés, in the Colombian Caribbean, where so much, and yet so little, has changed. For a start, Veronica seems to understand that her relationship with the island, something that used to be so familiar, is now something altogether different, and with that readers witness a rediscovery of the island—and by extension the Caribbean itself—through the eyes and experience of a young chronicler who is neither from here nor there: she is an islander accustomed to life in the big city; a native with Raizal blood, but also Irish, Scottish, and Jamaican blood, blood from the island of San Andrés and from the continent, all coursing through her veins.

Upon returning to the island, Veronica tours the house that once belonged to her parents, and discovers an old photograph in a long-forgotten suitcase. In it is a man in his forties standing next to a seated woman, not even in her thirties, his hand on her shoulder. It’s labelled: 1912, Kingston, Jamaica. It’s none other than Jeremiah Lynton and Rebecca Bowie—her great-great-grandparents. It’s the first time Veronica has ever seen this photo; nevertheless, she knows who they are and why her residence and circulation card label her as Raizal. Up until that moment she knew little to nothing of her ancestors, but after a (seemingly) chance encounter with Maa Josephine—an old Raizal woman she meets on the outskirts of a First Baptist Church Gospel concert—the picture and the names printed on it will become a question constantly gnawing at her for an answer to its origin. Unable to speak Creole, and with skin paler than those surrounding her, Veronica will take up the quest to find her roots and place on the island. And although San Andrés’ and Providence’s colonial past may be hidden away from her (as it is from many of us Colombians), Jeremiah and Rebecca’s great-great-granddaughter will ignite a search for the truth by unraveling hidden and silenced histories.

A highlight of the novel, on one hand, is the author’s particular representation of the greater Caribbean. Decluttered of cultural stereotypes, picturesque beach paradises and cocktails, Bendek deepens the reader’s understanding of a region that is the product of a complex colonial past and a victim of contemporary circumstances, in a difficult era comprised of rampant tourism, overpopulation, poor infrastructure, the inefficiency of public works, gross exploitation of natural resources, and corruption, among so many other things. But still, among all these maladies, there is a definite beauty: the cadence of the Raizal language, the community that bands together to resist the “thinking rundowns,” the reggae, calipso, and zouk, and of course the massive cultural hybridization of “a world that brought together everything in the Caribbean.”

Bendek excels at conveying the ethical position that the narrator assumes, and the conscientiousness of their position. Veronica Baruq often turns inwards to find the blind spot of her privilege. She knows that bias is an invisible, silent enemy and takes her time unraveling it. “My perspective comes from bricks and mortar, from air conditioning,” she states in a lucid and distressed manner; “I feel as though I’ve been an accomplice to something,” she judges. By positioning her place in the world in such a critical manner, the narrator implicitly compels the reader to do the same.

With this novel, winner of the 2018 Elisa Mújica Novel Award from Idartes and Laguna Libros, Bendek manages to revisit the ultimate Latin American and Caribbean (maybe even universal) question about identity. If in the sixties and seventies the works that were born out of the literary Boom revolved around the idea of Latin America, then this novel is certainly based around something else entirely. Islander, Raizal, San Andresean, Colombian, Caribbean… what is all this about? Well, it’s not easy getting into these topics, and yet, one of the novel’s greatest accomplishments is its approach to them from a diverse range of registers and discourses. In Los cristales de la sal [The salt crystals] the poetic voice (nostalgic and well cared for) coexists quite harmoniously with the chronicle (detailed, engaging), journalistic discourse (deeply committed), and, in certain way, the historical point of view (“historical” with a lower-case “h,” defying official History, so white and masculine until now).

In Los cristales de la sal, Bendek doesn’t just represent the complexities of San Andrés and the Caribbean; rather, she offers them to her readers, leaving them with a series of questions that must be further delved into. Identity is always under construction, and nothing can ever fully determine it. Readers will feel this, alongside Veronica, on her journey back home.

Rodrigo Mariño-López

Bard Early College, D.C.

Translated by Germán Rieckehoff-Strong