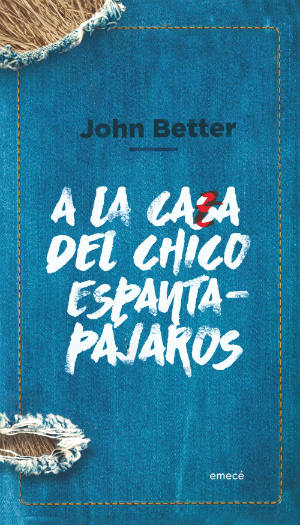

A la casa del chico espantapájaros. John Better. Bogotá: Emecé. 2016. 220 pages.

A la casa del chico espantapájaros [At the house of the scarecrow boy], a novel by Jhon Better, a writer from Barranquilla, has recently appeared under the imprint of the publishing house Emecé. A combination of memory and image through the eyes of a character named Greg. The narrative is organized into short chapters and delves mostly into childhood memories. Barranquilla is an unpleasant city inhabited by heat where Greg writes in his notebook to keep memories and experiences by means of written record. Some stories are evoked from his diary, and others are told in present time. A painting of dogs playing poker, the mysterious Albino Man, and a troubled relationship with a hysterical mother who doesn’t accept the sexual orientation of her youngest son, to name a few. In turn, like a spirit that permeates everything, there is something that keeps the characters alive, “something that burned like oil. Something that ignited our lives. A flammable element that was added to the fear, frustration, and neglect that seized us in those years. That thing was love” (pp. 14). A strong word for Colombian literature, which to a large extent are marked by contrary signs like death, war, and violence.

A la casa del chico espantapájaros [At the house of the scarecrow boy], a novel by Jhon Better, a writer from Barranquilla, has recently appeared under the imprint of the publishing house Emecé. A combination of memory and image through the eyes of a character named Greg. The narrative is organized into short chapters and delves mostly into childhood memories. Barranquilla is an unpleasant city inhabited by heat where Greg writes in his notebook to keep memories and experiences by means of written record. Some stories are evoked from his diary, and others are told in present time. A painting of dogs playing poker, the mysterious Albino Man, and a troubled relationship with a hysterical mother who doesn’t accept the sexual orientation of her youngest son, to name a few. In turn, like a spirit that permeates everything, there is something that keeps the characters alive, “something that burned like oil. Something that ignited our lives. A flammable element that was added to the fear, frustration, and neglect that seized us in those years. That thing was love” (pp. 14). A strong word for Colombian literature, which to a large extent are marked by contrary signs like death, war, and violence.

Colombian narrative tends to be more and more fragmented, like that reflected in Better’s novel. This type of narration restores storytelling from a local perspective, as it does not revolve around communicating from American and French influences. Even if in Better they there are aspects of Carver and Capote, the Latin American magic of the warmth of the characters, and the double fiction of reality give a marvelous touch to this realist and at times fantastical story. Greg, the boy scarecrow, has a head full of straw, not like an artifice of magic realism, but like the involuntary condition of a hyperbolic life that is diluted with imagination.

A la casa del chico espantapájaros is a journey to the origin of memories. In a small courtyard, the narrator, Greg, meets his childhood and adolescence alternated with his adulthood. In present time, Greg lives with Sandy, an intrusive woman who barges into his house like the female characters of Truman Capote who appear when least expected, and with WC Boy, a biker who loves and defends him. Greg, in his adult life, evokes images of his home in Las Nieves, a neighborhood in Barranquilla, when he lived with his mother and grandmother. The butchering of hens, his first sexual encounters, some friends from school, and holidays such as Christmas or Halloween, leap out to the reader and become small images in an endless river of memories.

One new element in his narrative is music as the existential condition of the characters. Greg has an in-depth knowledge of David Bowie, The Clash, Nina Hagen and Iggy Pop; it is not the now classic vallenato or Caribbean salsa of our writers. For Better, rumba isn’t a juvenile exploration as it is for Andrés Caicedo—an author to whom he is compared on the promotional book’s promotional band—, but one that plunges us into a comical, yet at the same time dense and confusing dimension, up to the point of making us feel alone in the middle of the dance floor. In a passage about the deep understanding of music, he says: “To see a landscape run passed the window of a moving car while you listen to a song is a matter of abstraction. The strip of vegetation in the scenery becomes linked with the tape turning in the TKD inside the tape deck.” It is possible to momentarily live that understanding, and perhaps that’s why his novel has flashes of lucidity, in addition to its importance for delving into the levels of memory and brings us fragmented elements, unfinished micro-stories, stories that never end, but with which one can always begin.

Ezequiel Quintero Gallego

Translated by Sam Marino