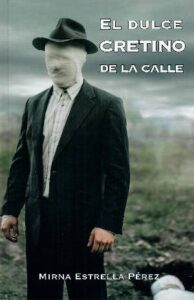

San Juan: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. 2021. 184 pages.

In front of the entrance to the New York County Criminal Court, the sculpture of a modern Medusa inverts the symbol of the monster-woman decapitated by Perseus. The naked and slender Gorgon of the twenty-first century, a work by sculptor Luciano Garbati, wields a sword in one hand and a man’s head in the other. Up to this point, it would portray an exact subversion of the Greek myth, according to which Medusa, raped and impregnated by Poseidon, was charged for his violation and punished by becoming a destructive beauty for men, until her final undoing at the hands of the “hero.”

In front of the entrance to the New York County Criminal Court, the sculpture of a modern Medusa inverts the symbol of the monster-woman decapitated by Perseus. The naked and slender Gorgon of the twenty-first century, a work by sculptor Luciano Garbati, wields a sword in one hand and a man’s head in the other. Up to this point, it would portray an exact subversion of the Greek myth, according to which Medusa, raped and impregnated by Poseidon, was charged for his violation and punished by becoming a destructive beauty for men, until her final undoing at the hands of the “hero.”

Upon close examination, however, and looking into her eyes (the thing the men from the myth could not do for fear of being turned to stone), the new Medusa does not exactly represent an “eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” The reinterpretation of the myth places us squarely in the present of the #MeToo movement and the role of courts in the search for justice for real women, not mythological characters. The contemporary female executioner does not bear the triumphant expression that art over the centuries has given to the victorious Perseus. Implicit in her eyes, in her expression, in her posture, there remains an unresolved conflict.

“Damage” was a euphemism employed in the popular speech in some Latin American countries to refer to the trauma of sexual violence. It is precisely this damage, or these damages, that is addressed in El dulce cretino de la calle, the debut novel by Puerto Rican writer Mirna Estrella Pérez. The book, a work of noir fiction, narrates the story of a “damaged” family clan. A crosshatching of incest, pedophilia, domestic violence, and parental negligence unfolds through the readings, together with the day to day life of a neighborhood assailed by child kidnapping, human trafficking, rape, and a murder, without the crimes being reported or justice being done. The surviving victims, in this novel, will not see their perpetrators in court.

Though this very brief work has a lot in common with the New York Medusa, it is not the narration of the act of decapitation of the male, nor is it a feminist battle cry. The main victimizers in the story are indeed men, but the author has enough insight to penetrate into the dual psychology developed by some of the female characters. (“To what extent can the victim resemble the victimizer? Do they merge at times? Might it be possible to play both roles? She felt that it was possible.”) In a text of direct language, these questions, formulated by Olga, the youngest member of the Vivar clan, sum up the author’s objective of demystification: gender-based violence has more nuance than we recognize, and it can be observed particularly in oppressor-oppressed female characters who are at the origin of incest, or in abused girls who grow up to be adult aggressors, or passive aggressors. The cycle of violence remains sealed for a society that perpetuates the power of the aggressor through secretism, complicity, or indifference disguised as familial respect.

Several sex crimes and two deaths traverse the pages of the book. The grotesque and the monstrous are inserted into what could have been a common story, were it not for the fact that the author reveals a vast understanding about everything that contributes to the acquisition of “damage.” Without sentimentalism or dramatic effects, the plot strips down the criminal consequences that could be brought about by indifference. What is important is not finding out who did what or why, but rather how circumstances take place that allow for the monstrous to occur. The narration, written in third person, avoids a testimonial tone (in this aspect the author stands apart from writers like Isabelle Allende, Laura Esquivel, and Esmeralda Santiago…). However, this narrative voice could belong to Olga, who finds something more in the past than the answer she was seeking about a family sin and the disgrace that followed it, or the identity of the person who perpetrated the femicide that was her obsession during childhood. That something more guides her to the questions she must ask in order to understand her own affective distortions and her potential to become an aggressor. At this point of contact between the young girl and her relatives, we are torn away from her obsession with the crime and dropped into a terrain that is more domestic, quotidian, and subtly terrifying.

Before her foray into narrative, Mirna Estrella Pérez made a name for herself in Puerto Rico as a poet. Beginning in the first decade of the twenty-first century, she published the poetry collections Ecos de Eva, Manifiesto sobre las tristes, and Miss Carrusel. In 2021, as her novel was being published, she bolstered her poetic work by earning her country’s main awards in this literary genre: first place at the Festival Internacional de Poesía de Puerto Rico for the volume Fallé en calcular la brutalidad de los años (Trabalis Editores, 2021); the National Poetry Prize of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture for Un kilo de duda en la saliva (Editorial ICP, 2021); and third place in the Certamen de Poesía José Gautier Benítez for the unpublished work Yo quisiera estar tan lejos como está la suerte.

In the novel, the author recaptures and develops the imaginary elements already present in her poetry, especially the nuanced and hazy intersections between body, desire, sexuality, and morality. The Medusas in El dulce cretino de la calle do not necessarily decapitate their Perseuses; they are women busy with getting to the bottom of their own story and engaging with the damage that they, their mothers, or their grandmothers received (“For the girl, it was important to understand the tendency: what was the possibility that she, her sister, her absent cousins would repeat the patterns? Is it biological, generational, environmental, a little of everything, just luck, bad luck?”). Building this narrative piece by piece becomes a cruel but necessary step to take before embarking down new roads: “I need you to tell me everything. What hurts the most.”