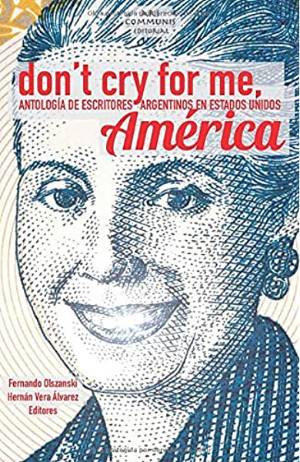

Don’t cry for me, América: antología de escritores argentinos en Estados Unidos. Editors, Fernando Olszanski and Hernán Vera Álvarez. Chicago: Ars Communis. 2020. 219 pages.

Anthologies are an interesting barometer for literature written in Spanish in the United States. What were once only sporadic and canonical just a few decades ago are now frequent and thematic. When compiling explicitly migrant literature, it is natural that the author’s birthplace be an important factor in selecting the work. Such is the case with an anthology like Don’t cry for me, América: antología de escritores argentinos en Estados Unidos [Don’t cry for me, America: anthology of Argentine writers in the United States].

Anthologies are an interesting barometer for literature written in Spanish in the United States. What were once only sporadic and canonical just a few decades ago are now frequent and thematic. When compiling explicitly migrant literature, it is natural that the author’s birthplace be an important factor in selecting the work. Such is the case with an anthology like Don’t cry for me, América: antología de escritores argentinos en Estados Unidos [Don’t cry for me, America: anthology of Argentine writers in the United States].

Fernando Olszanski and Hernán Vera Álvarez, editors of Don’t cry for me, América, point to the fact that “the relationship between Argentine writers and the United States is just as fertile as it is complex.” They recognize that in the anthology’s texts, “country of origin is a constant. With one eye for analysis while the other waxes nostalgic, the resulting vision is sometimes one of longing, while other times it is one of mistrust.”

In “La palabra justa” [The perfect word], Gastón Virkel’s son, a fourteen-year-old born in Miami who has never spent more than a month in the Southern Hemisphere, identifies himself by saying, “I am Argentino.” What truly defines the Argentine condition if it can be constructed in South Beach? This is the question that the fifteen authors in Don’t cry for me, América touch upon most—fifteen authors who, at some point, all made the journey from Argentina to the United States and confronted (confront) not only their own redefinition and rediscovery inherent in the migration process, but also the permanent tension that lies between an independent national identity that is distinct from other Latin American countries, and the common idea in the United States that views Latinness as a uniform and constant element throughout the entire region.

“La palabra justa” is not the only work to present children as mirrors in which identity gets revealed as absence. This is also the case in Gabriel Goldberg’s “Trescientos fósforos mojados” [Three hundred wet matches], Gisela Heffes’ “Volver” [Return] and Lila Zemborain’s “Patria” [Homeland]. Furthermore, in both “Volver” and “Patria,” this emptiness blossoms during vacations to Argentina. Immigrants return home only to discover that it no longer belongs to them because their children do not recognize it as their own. Sometimes this not belonging is an act of violence, as we see in Javier Fentino’s “El tamaño del miedo” [The size of fear], and sometimes a reminder of “the others” allows us to understand that there is only one “other,” as in “Babelian,” by Eduardo D. Rubin.

The gaze from which we recognize “the other” is always introspective. To look outward is to see a fractured version of oneself, as if the immigrant were inhabiting two realities at the same time in a country they now call home, but will perhaps never be fully theirs. Gladys Ilarregui’s “La tierra de uno: in two chapters” [One’s land: in two chapters] and “259 saltos, un inmortal” [259 leaps, one immortal], by Alicia Kozameh tackle this double reality, which becomes the metaphor of milanesa as a kind of cultural Trojan Horse in Adriana Briff’s “La aproximación de los tiempos” [The closeness of other times]. Claudio Iván Remeseira’s “Carta desde Nueva York” [Letter from New York] and Hernán Vera Álvarez’s “Misivas electrónicas” [Electronic missives] thoughtfully contend with this new identity, while Pablo Brescia’s “Nuestras imposibilidades” [Our impossibilities], finds it necessary to rebel against it.

Identity is constructed upon contrasts, memories, absences, and confrontations in a permanent feedback loop. Because new immigrants make this journey year after year, some will write about it. Thus, efforts like Don’t cry for me, América are pertinent, necessary and worth repeating with a certain frequency so as to recognize the particularity of any cohort, just as much as its universality.

Luis Alejandro Ordóñez

Translated by Daniel Hurwitz-Goodman