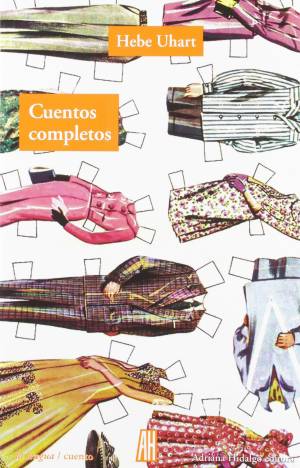

Cuentos completos. Hebe Uhart. Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo Editora. 2019. 784 pages.

In the short story “Desfulanizar,” the narrator remembers one of her father’s rules: to greet the townspeople so they didn’t think she was prideful. But the narrator didn’t care what other people thought. She also didn’t care that her father told her about how once, when he was a child and didn’t say hello to someone, he knew he’d done wrong and deserved to be punished. To his daughter, this story, which she considered from a different time, went against her effort to “make people more real, to understand them in their own way, not tied to that deadly routine.” And there it is—the kernel of this piece of writing by Hebe Uhart(Moreno, Buenos Aires Province, 1936 – Buenos Aires, 2018). It is revealed over the course of Cuentos completos [Complete Stories], published by Adriana Hidalgo Editora. “Desfulanizar” means to cleanse the subject of preconceived notions, from the mark of social stereotypes, and to get back to finding their blurred individuality, to observing, and above all, tirelessly listening. This must be done without the pretense of changing them; rather, it is a matter of recognizing their dormant complexity over the noise of “should be.”

In the short story “Desfulanizar,” the narrator remembers one of her father’s rules: to greet the townspeople so they didn’t think she was prideful. But the narrator didn’t care what other people thought. She also didn’t care that her father told her about how once, when he was a child and didn’t say hello to someone, he knew he’d done wrong and deserved to be punished. To his daughter, this story, which she considered from a different time, went against her effort to “make people more real, to understand them in their own way, not tied to that deadly routine.” And there it is—the kernel of this piece of writing by Hebe Uhart(Moreno, Buenos Aires Province, 1936 – Buenos Aires, 2018). It is revealed over the course of Cuentos completos [Complete Stories], published by Adriana Hidalgo Editora. “Desfulanizar” means to cleanse the subject of preconceived notions, from the mark of social stereotypes, and to get back to finding their blurred individuality, to observing, and above all, tirelessly listening. This must be done without the pretense of changing them; rather, it is a matter of recognizing their dormant complexity over the noise of “should be.”

And what is real about Hebe Uhart? This much seems certain: she was a writer far from dirty realism and closer to a tender, spontaneous version of it. However, in the case of Uhart, the question should not be what, but how. This concerns what we see as much as the way we see it, because we will only be able to find the subject’s uniqueness if we watch attently, if we know how to wait, and if we direct our attention toward concrete detail. If we desfulanizar our gaze, and we objectivize it before a reality where, as Liliana Villanueva would point out in Las clases de Hebe Uhart [The classes of Hebe Uhart] (Blatt & Ríos, 2015), “the fact itself doesn’t matter so much as how it affects me and the character.” This method isn’t so much about contemplation or the pre-eminence of a cliché. Unlike Borges, for example, whom she knew to work with ideas rather than human beings, Uhart found literature in “that place prior to the idea.” It has more to do with one’s calling to take over and characterize that which still offers an astonishing reality, reflecting our fragile essence and existence. So it isn’t by accident that her reading material tends toward the sense of subtle irony in behavior of Katherine Mansfield, or the descriptions of Lucio Mansilla in Una excursión a los indios ranqueles [An excursion to the Ranquel Indians] (1870), an author she admired for his defense of writing when he felt like it, with an orality close to conversation.

Thus, we see how Uhart’s emphasis is placed on the sides, or what we might consider as such. That is to say, the identity that we work to marginalize, where those things that we have yet to explore still lie, that haven’t been used up by “that deadly routine.” Uhart’s characters are more interested in a bedbug than the Eiffel Tower; or in knowing people more for “how they sneeze than for the various ideas they might hold,” as in the story “Él” [Him]. The same thing happens with her use of language; Uhart’s character isn’t interested in puritanical speech, in the artificiality of the neutral voice. The Dutch tourist stammers along, mixing and incorporating words as he learns them; the student says “lumbrí” instead of lombriz, and his teacher allows it because she ajudges it “more humble, shady, intimate.” It is this empathy that keeps meaning from becoming bogged down in what is done; rather, she pieces it together and offers new meaning, desfulanizándolo, making it more real. For Uhart, real means exceptional, on the side of liberty. This is particularly evident in her style in “Guiando la hiedra” [Guiding the ivy], one of her most resonant stories and the one where there is perhaps the most evidence of how the continuity of the plot can jump—unique to her earliest stories, from between 1962 and 1970—to the continuity of meaning and metaphor, which will almost naturally lend itself later to the chronicle, another genre in which Uhart distinguishes herself.

What is certain is that in a world hungry for hard-hitting “real facts,” where the latest news repeats and greets itself endlessly, rediscovering Hebe Uhart’s stories both surprises and stimulates. Her non-existent servility and complacence make her literature an inexhaustible fount of uncertainty, not without humor, honestly submerged in that place before the idea—or the news of the day—where investitures are laughable and even useless, and where we are naked and lost, disoriented in the life that we confront. This is where “the human being is radically alone,” to paraphrase the title of another of her stories. It seems distressing, but Uhart’s wisdom is repulsed by the end of the world: which is nothing more or less than when you tell the stories they want you to tell, and not the ones you desire yourself.

Ricardo Montiel

Translated by Michael Redzich

Ricardo Montiel (Maracaibo, Venezuela, 1982) has published the verse collections Ciudad blanca sobre fondo blanco (Ediciones del Movimiento, 2015) and Agonía de los días terrestres (Caleta Olivia – Rangún, 2018; El Taller Blanco Ediciones, 2020). His writing has appeared in digital and print media in Argentina, Costa Rica, Spain, Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela. He co-edited the digital magazine Merece una reseña, and he has lived in Buenos Aires since 2007.

Michael Redzich is currently studying law at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. He graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 2017 with a BA in Spanish and a BA in Letters. His interest in Latin American literature sprouted early in his Spanish education, but grew considerably during his time in Buenos Aires, where he lived from 2014-2016. Michael was one of the first OU undergraduate students to become involved with LALT, and he continues to work with the journal as a translator and editor-at-large.