Translator’s Note:

Translator’s Note:

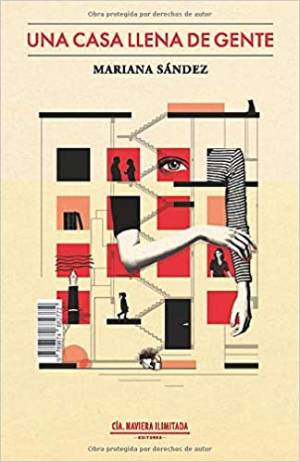

This is a surprisingly accomplished read for a first novel. Sández lends the simple premise—what happens when different families and characters find themselves forced to share living space—extraordinary depth with her empathetic, witty, and deeply intelligent depictions of the different emotional bonds that we form in life and the grief that follows our losing them. Her characters are memorable and well-drawn; readers will cringe along when Granny and Gloria have the mic but are especially likely to connect with Leila and Fernando and their obsession with books, which they prioritize over almost everything else. Una casa llena de gente has been a commercial success for Companía Naviera in Argentina in an extremely difficult market and its universal themes would seem to promise excellent commercial potential elsewhere. Something for readers of Elena Ferrante or John Williams.

—Kit Maude

***

Foundations

Yes, it could begin this way, right here, just like that, in a rather slow and ponderous way, in this neutral place that belongs to all and to none, where people pass by almost without seeing each other, where the life of the building regularly and distinctly resounds.

Georges Perec, Life, A User’s Manual

It’ll probably be dark by the time you get there, a little late because rehearsals went over time, as usual. Once you finally ring the doorbell, your father will ask you to go down to the basement with him. At your predictable query; why all the mystery, why on earth would you need to go down to the basement at this hour, he’ll tell you that it’s to look through some things that have been stored down there for years. You’ll ask whether your siblings are coming. No, he’ll say, just you. I want to give you something. It’ll be damp and cold in the storage area with its horribly symmetrical wire cages full of useless things. You won’t understand why you need to do this when you’re still feeling so fragile and sensitive. Choosing to immerse yourselves in a place so like a prison, or a cemetery, at a time like this.

‘Are you sure? Don’t you want to do this later?’ you’ll say when you see a cockroach scurry out from under one of the mouldy boxes. Perhaps you’ll wonder aloud whether anyone ever cleans down there. You’ll try to avoid contact with the walls; you’ll pull your jumper tight around your body to protect yourself and throw another loop of one of those long scarves you like to wear, so long that they drag along the ground, around your neck. Your father will ignore you and tell you that he needs help finding something, he’s thinking of getting ready to move. You’ll think that sounds sensible, he shouldn’t stay in the flat he shared with you, and more importantly your mother, all those years. The flat where he nursed her in her final illness. In fact, you’ll reflect that you could help move things along so he can get out of there sooner. Then you’ll wonder why he didn’t ask your siblings for help too. But you won’t have time to ask the question. ‘Mummy asked me to give you a box of notebooks she wrote for you.’

Mummy.

‘Mummy?’

‘Mummy.’

You’ll be stunned. You never would have thought that she left something like that for you. Not even a message or a letter, although she had time enough to say goodbye in the way she liked best: in writing. A whole box of notebooks though.

‘Oh, I see,’ you’ll say as your father, crouched down with his back to you, heaves boxes around. ‘They must be my exercise books from school or the folders of drawings I did when I was a girl. That’s so typical of her, always writing my biography.’ The last word will echo in the lifeless, junk-infested cavern.

‘No, all that’s here too, packed away over there,’ he’ll say, pointing towards the back wall at a box much older than the others, which is stuffed full to bursting: ‘“Charo’s drawings and schoolwork.” Leave them there if you don’t have enough space at home. Until you settle somewhere with Juan or I move and we need to clear everything out,’ he’ll add, his face red with the effort, veins bulging in his forehead. From which he’ll mop sweat. The place is freezing, but he’ll be hot. ‘But maybe you should sort through them some time, to see what’s worth keeping.’

‘She wrote notebooks for me? Are you sure?’

Your father will look absolutely lost, it won’t seem as though he understands a thing. He’ll react on a delay like an automaton, surrounded by a buzzing sound that never leaves him. You won’t think he heard you.

‘Fernando!’ you’ll have forgotten when or why you started calling your parents by their first names but it was when you were very young: almost certainly because your siblings called your mother Leila or Lei.

‘What?’

He’ll fix his bulging eyes on you, eyes that have been red and vacant for months. It hurts to see how much he’s aged. Then you’ll wonder whether people see you that way: haggard and worn out. It’ll be hard for you to accept how fragile he looks, the barely perceptible trembling, which is down to age but got worse after the recent trauma. ‘Take them and go through them whenever you want. She wrote them, yes. She asked me to give them to you once the worst was over. Wait if you have to, you don’t need to read them yet. I couldn’t. You don’t even need to take them right now, you can pick them up later. But it was my responsibility to let you know that they’re here, she was very insistent.’

In spite of yourself, you’ll agree to take them.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Of course,’ you’ll say hesitantly.

Fernando will drag out the tall, narrow box and leave it at your feet in the passageway. You’ll have the strange sensation of having posted bail for someone. You’ll wipe the dirt from the lid. To one side, written in blue marker in your mother’s handwriting, it will read: ‘For Charo’. You’ll be teary. Your father will give you a hug, you’ll hug him back. He’ll take the box out to the car and you’ll say goodbye on the pavement.

‘Get your husband to take it out of the car, please don’t try to lift it yourself.’

‘No, daddy, don’t worry. Juan will take care of it,’ you’ll hurry around to the other side of the car to get in before he sees you crying, which will start the moment the door is closed. You’ll let out the emotion that has been building inside of you all this time, head lowered, pretending that you’re putting the key in the ignition and turning on the radio. As you try to get a hold of yourself, glad that it’s dark and the windows are dirty (you never get the car washed), you’ll start the engine, change radio stations to something not so depressing and wave so that your hand covers your face. As you pull away you’ll see him receding in the rear-view mirror. Don’t be upset, he’ll get over it in time. Just as you will.

If you look up the address on Google Maps and zoom in as far as you can, you’ll just make out the yellow oblong, big enough for a sizeable monument, fragile as a sandcastle. If you’re not familiar with its history, say if you were scrolling down the streets looking for a specific address, all you’d see is one unremarkable building among many. A weak, indistinct form that looks as though the architects knocked it off in a hurry. The world has grown full of similar buildings, as though lives have grown less valuable even though they’re lasting longer than ever. The miraculous part is that where before there was just one large house they managed to fit four modern flats in two volumes, plus three garages in front, a basement and a garden. They made full use of the room they had to play with.

We, the Almeida family, lived in one of the duplexes for many years. Whenever I was asked where I lived, by the mother of a friend at school for instance, I’d say: ‘In that sandcastle over there, see?’ pointing at the roof dwarfed by two larger buildings on either side. ‘Funny girl,’ they’d think, but they’d have to admit that it did look small, scruffy and rather sunken.

From now on, then, we shall refer to it as the castle, sandcastle, châtelet, château or castello.

The Almeida were the first to move into the châtelet, before it had officially opened, when it was still lacking one or two essential features such as a gas connection and paint on the doors, among other modern amenities. Mum found herself forced to do battle with hordes of men in overalls who shed dust in the common areas and never seemed ready to leave. ‘Next week,’ or ‘Friday at the latest. If it doesn’t rain,’ were typical answers to Leila’s plaintive ‘When?’ The builders were working with the urgency of those who didn’t want to be the last one out that one often encounters in delayed builds where things don’t quite seem to have gone to plan: unfinished patches, oversights, fixtures that one really oughtn’t to look at too closely.

‘Do it right! I want you to deliver this house in fit condition,’ she’d demand angrily, trying to maintain her British elegance and composure. The builders would stare at her and then look at each other before shrugging in an unconvincing effort to project concern. They’d always say yes to whatever it was she was asking, whether they understood the question or not. They knew there was safety in numbers and that at the end of the day the blame lay with the construction company, the owners, the bosses. They just earned their daily wage and took their helmets off to other jobs where they weren’t harried all day by an exacting crazywoman who ran around like a nagging housewife. For the battles that required complaints, negotiation, the return of unfit products or haggling over prices, my father knew it was best to deploy his best soldier: Leila Ross de Almeida. He would only make an appearance if a deal couldn’t be reached, which was unlikely. Mum knew how to handle herself in situations like these, she’d received years of specialist training from an expert in domestic management: my dear Granny.

The other residents arrived in dribs and drabs, not long after us. My siblings and I were dying to find out more about them. Meanwhile, we took possession of our rooms: for the first time, we would no longer be forced to sleep in the same tiny, ramshackle bedroom. The castello awaited with royal bedchambers for each of us – the chambers may not have been particularly large but compared to what we had before they seemed like paradise – along with a garden, a real garden just for us. From there we made our own discoveries: my brother was thrilled to see a built-in barbecue and ready-made space in which to host his friends. My sister was enchanted by the prospect of seeing something green rather than the flaking wall our old window looked out onto and being able to sunbathe. The latter most of all: hours with her earbuds plugged in like hearing aids oblivious to everything but the progressive crisping of her skin. I had a lawn to run around on, fresh air to play in, birds and insects as playmates, not to mention picnics and stuffed animal camp outs.

The two months after we moved in were nothing but revelations. The construction hiccups got sorted out, more or less, the paperwork was put in order and the initial uncertainty began to wane. Like a new settlement, we had to start from scratch, build the foundations and establish boundaries, which Leila regarded as being manifestly obvious, as plain as the air you breathe, but if they weren’t written down on paper they didn’t have any legal or bodily weight, they’d wither and fall from the tree like overripe fruit. Once they were splattered over the ground then ‘You get jam instead of a civic code!’ she’d declare dramatically. I don’t know how it was worked out, I get the feeling that the Co-owners Agreement was written and re-written several times on the fly, in response to events as they happened with additions, excisions and amendments, as is often the case in these situations. I knew that things were improving when the words ‘regulations’ and ‘co-ownership’ appeared less frequently in my parents’ conversations, which also began to grow less heated.

However, the moment people moved in to the duplex above us it was my father’s turn to pontificate: the parquet flooring must be as thin as a communion wafer, they can barely have used any mortar, let alone plaster, or if they did it they must have wasted it, the acoustics were awful, we could hear the unimaginable. Maybe in their hurry they’d mistaken polystyrene for brick, or rubber or air. The construction company had screwed everyone over for fuck’s sake, the fucking, shitty, dirty little bastards. Now it was mum’s turn to play peacemaker: You’re absolutely right, Fernando, but please stop swearing in front of the children, we’ll talk about it later. We soon understood what he was so upset about: in addition to the sound of footsteps and other movements from upstairs, we could hear the neighbours’ conversations whenever they raised their voices even a little and especially if they shouted or spoke on the phone anywhere near a window, and we assumed that they could hear a good portion of our conversations as well. Fernando cursed the day he was blind and dumb enough to let that pair of obstinate women talk him into moving into the house, but he calmed down almost immediately, apparently seeming to forget about it, or stop caring at least. He was always able to turn the page. Mum, on the other hand was trapped on a tight rope, going back and forth, back and forth. He always ended up being proved right, she’d say, why couldn’t she learn to listen to him, stupid, stupid, idiot, she chastised herself much more than was called for until dad said something like: Stop it, it’s done, don’t make such a fuss, it’s not worth it, it’s just stuff, the only thing that can’t be worked out is death. Some of his favourite phrases. The good thing about them was that they always balanced each other out, passing the burden back and forth, though mum’s side of the scales was always weighed down a little more, intangibly closer to breaking point.

Meanwhile, as the years went on Granny – who had been a leading proponent of the move to the Chateau, which we eventually came to call, with no small degree of bitterness, the catastrophe – absolved herself of any blame at all. Or at least she didn’t reveal a hint of regret. But I know her better than that, I think that she must have suffered to some extent. In some closely guarded part of her soul, it must have hurt to see the impact of her decisions. Still, it would be utterly unfair to assign all of the blame onto her. Which is exactly what my mother did – behind Granny’s back – whenever she got the chance. We’d tell her that there was no way Granny could have known, no one could. She might be a bossy old woman but that doesn’t make her God. Everyone needs to take responsibility for their actions.

‘We’re packed like sardines in here, don’t you think?’ Leila would remark to Fernando, prompted by Granny’s constant needling. I can easily imagine Granny declaring a health emergency over the three room flat where we lived when I was born and stayed until I was seven. Like most children of divorced parents my siblings split their time between two households but sometimes – to my great joy – they’d spend a whole week with us if their mother was away for work. Julian was seven years older than me and Rocio five. They told me that ever since I was brought home from the maternity ward they’d had to share a tiny bedroom containing a pair of sailor’s cots, a crib and a wardrobe where dad kept his suits because there wasn’t enough space in the master bedroom. The small kitchen abutted what was little more than a gesture to a utility room, clothes were hung out to dry on the back balcony because the front one had been closed off and turned into a studio where mum could work in peace from us and dad could speak to patients or their family members during emergencies. Only one of the two bathrooms had a bath. The other had been repurposed by Leila and Fernando into a tiny library for the overflow of books from other rooms. When all five of us were sitting in front of the TV, as often happened during my early childhood, the living room was crammed. My parents grew to be experts at finding films that pleased everyone in spite of the range of ages, which was very much to my benefit: my cinematic education was as precocious as any girl could wish for.

When she was being polite, the words in English Granny chose to describe our flat were shoe box. She pronounced the term with such aristocratic distinction that it took a moment to register as an insult. When she came round to visit, she would embark upon an unending stream of criticism – well-meant criticism born out of concern for her loved ones (and she very much saw us as belonging to her) – of the mess, the cracks in the cement floor, which she assured us was poor quality, the odd dead plant, the fact I was wearing hand-me-downs from my sister, which were often too big or too small, or the skill required to manoeuvre within a space she compared in all seriousness to the inside of a microwave. She’d declare that everything we do was on plain view to the entire world and rush to close the curtains. She herself always had her blinds closed to prevent the sunlight from fading carpets and sofas that visitors were hesitant to use for fear, I believe, of wearing them out. I remember how scared I was of dirtying the upholstery or tiles so shiny you could see your face in them. Her flat, which took up a whole floor, was lavishly decorated, not unlike a museum. To complete the picture, it’s worth noting that Granny always refused to drive my grandfather’s car because she was afraid of denting or scratching it, or getting a ticket, even though she kept her license up to date.

‘If only you’d thought twice before marrying a divorced man with two children…’ she’d start out, trying to sound casual, as though it were a passing thought.

She’d lick her finger before turning the page of a magazine, lift her tea cup, take a sip and look at me over the brim attempting to force a smile. As hard as she tried her lips never spread further than the diameter of even a small cup. Granny’s mouth wasn’t used to stretching out, it was far better acquainted with pursing: to drink tea, criticize or correct. Which must have been the cause of all those deep wrinkles that converged upon her upper lip. She was addicted to Earl Grey (and abhorred unusual tastes), water at boiling point, boiling point precisely, no more, no less, the secret to a proper cup of British tea is to get the boiling right, my dear. I could never tell whether the syllables squeezed so reluctantly from her lips because that was how Brits talked or because she was incapable of being open or expansive.

Grandpa Oscar, and Granny herself, explained that her character was a result of her heritage. I can’t count the number of times I wondered at this connection: why would someone be so grumpy just because they came from a certain country? Her parents had migrated from Winchester, in the south of England, to the south of Buenos Aires, Temperley or Banfield, when my granny was around fifteen years old, or a little later. I’m not sure what brought the move on. Grandpa Pepper (who had earned the nickname with his spicy sense of humour), my great-grandfather, worked on the railways and my granny stayed at home to help her mother raise her four younger siblings. Granny had already attended school in England, but the other four went to British schools in the area, one for boys, the other for girls. If I’m not mistaken, before she married, Granny worked as a primary school teacher at one of the schools.

I’ve also wondered whether it was the journey down from one south to another that was responsible for her prickly character because she never felt any affinity for her new country. Maybe if they’d stayed in Britain, my grandmother – who most likely wouldn’t have been my grandmother – would have turned out a sweet old lady of the kind one sees on homemade jam jars and regional sweet packaging, the kind who tend to their roses and take their fox terrier shopping in a basket. It was probably the geographical disruption that planted the seed for the vendetta of ‘if onlys’ that bubbled underneath everything she said.

At home, but also in a large part of the local neighbourhood, and the school community, people continued to speak English, a world of English had sprung up magically on Latin soil, as though they’d never left the isles at all. They spent their weekends at country clubs playing cricket, tennis, hockey or rugby. Or that game where you hit a pigeon back and forth… badminton. Beneath the team photographs that practically covered the walls, in the spaces between trophies, of one of my great uncles’ living room – Henry, the youngest and most competitive – the lists of surnames read Stirling, Mackenzie, Hamilton, Gilmore, Eaton, Campbell or Dodds.

I knew Dorothea Dodds, one of my Granny’s friends, a little. She was a kind of second mother for my mother, generous with all the love and warmth that my Granny withheld. Perhaps because Dorothea didn’t have children, a job, or a life of her own (she looked after her parents), not even a pet, she took a real shine to Leila and became her godmother. Hold on, she did have a cat because I remember playing with it when we went to see her. Then one day, when she was quite old, she decided to return to Britain. Mum wrote her letters, telling her that she was a role model, that she admired her because at the age of almost sixty she had decided to start a new life.

Emily Douglas, my grandmother, was English to the bone. Even the way she hugged the pillow was English (as though it were a lost fragment of the United Kingdom) and she refused to let anyone latinize her name: on no account was she to be called Emilia. Whenever someone made that mistake, she gave them a devastating glower evoking, by turns, a combine harvester, flame thrower or cornered swordfish. My grandpa Oscar, in contrast, was descended from Scottish ancestors who migrated to Argentina several generations earlier and had long since lost any semblance of Scotchness. He had a sharp wit when he wasn’t preoccupied by work, which was eighty-five percent of the time. During these periods he would be both physically and mentally withdrawn, a fugue I dubbed his ‘submarine state’, and the term soon caught on with the rest of the household. To make up for these voyages to the bottom of his self, whenever he resurfaced he offered to take my siblings or cousins and I ‘kiosking’, one of our favourite childhood verbs. It consisted of going to the local corner shop where he would let us pick out an enormous amount of sweets, whatever we wanted, regardless of cost or the damage they’d do to our teeth. Or sometimes, when he came into the house he’d announce a ‘Treasure Hunt!’ which was a signal for the children to jump on top of him (he was a large man) looking for sweets, lollypops and chocolates in all the different pockets of his person. It was like cracking open a human piñata.

We were allowed to call him Oscár, with the accent on the ‘a’ rather than the British pronunciation even if his surname was Ross and he was descended from a family with a crest that dated all the way back to Mary Stuart. Granny was the only one who called him Oscar, with the emphasis on the O. Or rather Oska, barely pronouncing the ‘r’ at all. But everyone had to admit that they adored one another.

Grandma Emily’s Britishness was apparent in everything she did. It stood out in the severe wit and irony of her conversation – she was always sparring, as though she thought she got points for brilliance and acidity – her thin, wiry, Saxon figure, her silvery white short hair that was once red, bright red in her youth, her insistence on getting around by bicycle until well into her seventies but most of all her habit of including English words and phrases in her conversation regardless of whether whoever she was speaking to understood them or not. When she switched from English to Spanish her voice grew shriller and her speech slower, as though the processing centre in her brain insisted on inspecting each and every sound and syllable before letting them out. When she was in the mood, however, she could speak Spanish well and fluently.

There was undoubtedly an Englishness in the ultramarine of eyes that had grown slanted under the weight of having to scrutinize and judge everything, absolutely everything. Mum inherited her linguistic skills and red hair but not the drooping, limpid eyes, which went to her younger sister, Aunt Vera. Leila’s were light green fading into a gentle brown with a yellowy sheen that glowed in the right weather. They were rounder than Granny’s (which isn’t to say that they were any more relaxed, there’s no getting away from some legacies).

‘If you’d listened to me, you wouldn’t be living in this pit right now,’ Granny would scold mum the way other people complained that their bones ached in certain weather. It must be quite unbearable. This is no way to live decently. Generally, her outbreaks of grumpiness, and joy, occurred in English. Unacceptable, advisable, indecent, and a pity were cornerstones of her vocabulary.

‘Really?’ Leila would bark back, infuriated. Her first concern was to protect me from the aerial bombardment to come: ‘Charo, go play in your room, please.’ I’d resist, I wanted to stay with her, to be with her in her time of need, shield her from the worst of Granny’s attack, which had already rained down on her far too often in her life. An indescribable intuition told me that if I was there she’d be easier on my mother. But mum was determined to protect me from the worst of Granny’s tongue-lashing. ‘Right now, go!’ Whatever her actual words or admonishments, all I heard was ‘Take cover men! To the bunker!’

The silence went on until I’d disappeared from their sight, although I still had eyes on them. I knew how to hide where I could watch and listen to their conversation unseen. In any case, the flat was so small there was nowhere I could go that was entirely out of earshot. I’d sit on the bottom shelf of a cupboard in the brief hall that led from the living room to the bedrooms and scratch away at the flaking cement floor. As I listened, I’d amuse myself at how the dust imploded, like an anthill caving in on itself. I could also hear them from my room if I sat next to the door or the bathroom if I left it ajar.

‘It’s not nearly so bad living here as you might think…’ said Mum reproachfully. ‘They’re good children, all three of them. They behave. And most importantly they love each other. You know how much it means to me that Charo has a brother and sister who love her? No, you don’t!’

‘Shh… Your daughter will hear you,’ Granny chided. It often seemed as though she were at her calmest when others were angry. I hated it when she called me ‘your daughter’ as though she didn’t recognize me as her granddaughter. From wherever I was hiding I’d think that if I were my mother, that would hurt very much.

Although I couldn’t see her because she had her back to me I knew that she was smiling one of those wobbly, unreadable smiles that made you want to burst into tears. Arranged that way, her features evoked the moment when the sun breaks through the clouds but it’s still raining. Her pinkish, freckled complexion darkened just like when clouds pass over the sun. Maybe it was my imagination but at moments like that her freckles disappeared into shadow, if you looked closely you’d see them disappear. I wanted to know if mine did the same thing, whether my freckles went out too – I was a faded version of mum: my hair a softer shade of red, my eyes a lighter green, my freckles floating on my face like lilies in a pond, we were a pair of pre-Raphaelite models, anaemic romantic visionaries – but nobody ever understood what I meant when I asked.

‘You’re suffocating me, mother,’ Leila said, already defeated, and she’d collapse back onto her chair, her head in her hands.

‘Everything suffocates you,’ Granny would reply in a softer tone suggesting that she might just regret her words or that her conscience was pricking her, but no. ‘You’re very wrong if you think I’m to blame for all this,’ she countered. ‘Having to support his family too, on the insubstantial salary of a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, whatever, it doesn’t matter. No, it’s worse, he doesn’t even have a medical degree. Keeping patients in the long term is difficult. That kind of madman is always now you see me now you don’t. Your husband the psychologist and you, a translator, what kind of five-person family, six if you count his ex, can live on that? Supporting two households, Who could possibly live like that? It’s just not normal. Or perhaps it is but not for people like us,’ her litany of complaints was accompanied by a graphic set of facial gestures led by a nose wrinkled up tight as though one of my brother’s football socks were being pressed against it. ‘All I’m saying is if you’d only listened to me…’ followed by a thick stream of I told you sos, I was right wasn’t Is, and If only you paid attention once in a whiles, interspersed with gibberish caught between two languages, all emerging from a rictus of a pursed mouth, a nodding head, and slowly blinking eyes. The indications of approval and reverence were directed inwardly, paying tribute to how right she had been. Granny was of the iron-clad conviction that it is possible to anticipate the future and avoid errors if one only scrutinizes their past and identifies the mistakes they’ve made. It was an approach to life that made the present a living hell.

Translated by Kit Maude