Editor’s Note: This essay was a finalist in LALT’s first-ever literary essay contest. We congratulate the author, Mariano Vespa, and we are proud to share his work with our readers, in the original Spanish and in English translation by George Henson.

Just a few weeks after the premature death of Carlos Eduardo Antonio Feiling (1961–1997), the philosopher Eduardo Grüner, in a tribute-dossier published in the magazine La Gandhi, notes that he

was perfectly aware that it is a mistake to think that because the genre novel points to a canon it presupposes some belief in eternity. Precisely the opposite is true: the idea of genre, if pursued to its end, leads to the most radical and irreducible (sometimes even conjunctural) historicity, attentive to the material conditions of its emergence.

After having devoted himself for more than a decade to academic excellence, with stays in New York and Nottingham, Feiling, who signed his works with the lineage of an Anglo-Saxon poet, C. E., and answered to the overfamiliar “Charlie” or “Carlitos,” proposed an anachronistic gesture: to conceive of novels of popular genres, which he realized with the detective novel El agua electrizada (1992), the historical adventure Un poeta nacional (1993), the thriller El mal menor (1996), and the unfinished fantasy La tierra esmeralda (1996).

El agua electrizada navigates in the confluence of different lines, autobiographical and contextual: the initial peripeteia or mystery, which drives the plot; the constant breaks in language, through which he translates not only his English lineage but also his experience as a teacher and translator of Latin poets; the context of a military post-dictatorship and the resonance of the Malvinas (Falklands) War for his generation, and the specter of leukemia, which haunted him for twelve years. As soon as it was published, the critic Alfredo Grieco y Bavio dubbed it a novel of “private loss” and, at the same time, “a political novel that refuses to rest on the correct ideological position.”

Minute for the crime

Tony Hope, a young Latin teacher, biting and alcoholic, receives a call from his mother that torments him: Juan Carlos—“El Indio”—a former high school classmate, dead from a dubious suicide. A piece of paper found in his friend’s pants acts as a catalyst for the confusion: “The case of the dead women in the bathtub.” Feiling turned to an investigation by the journalist and detective Enrique Sdrech in 1989, in which two very young cousins were found dead in a bathtub, in a state of decomposition. The character of El Indio is built around the biography of José Luis Ruiz, a former classmate during Feiling’s naval training in secondary school, a hero of the Malvinas War, who had died in uncertain circumstances: “The pistol had been fired with the left hand, unusual for a right-handed man,” (p.24). In this initial plot, Feiling references his own medical history, which he attributes to the victim, to sow more doubts about the protagonist and heighten the dilemma: “The type of leukemia for which he’d been treated—acute lymphoblastic?—had a high recovery rate; he’d gone untreated for more than two years, and was completely healthy. Whether suicide or accident, the questions why and how remained.” In other words, he combines two biographemes—his illness and that of Ruiz—in a single turn. He also employs this in the poem “País de mala muerte,” dedicated to J.L.R.: “Territorio del cáncer fueron luego los huesos, / la sangre, las pelotas, cuanto alcanza / un médico a punzar buscando gruesos / pecados de la carne con qué medir la lanza” [Territory of cancer were then the bones, / the blood, the balls, how much a doctor reaches / to prick looking for thick / sins of the flesh with which to measure the lance].

Mysterious objects

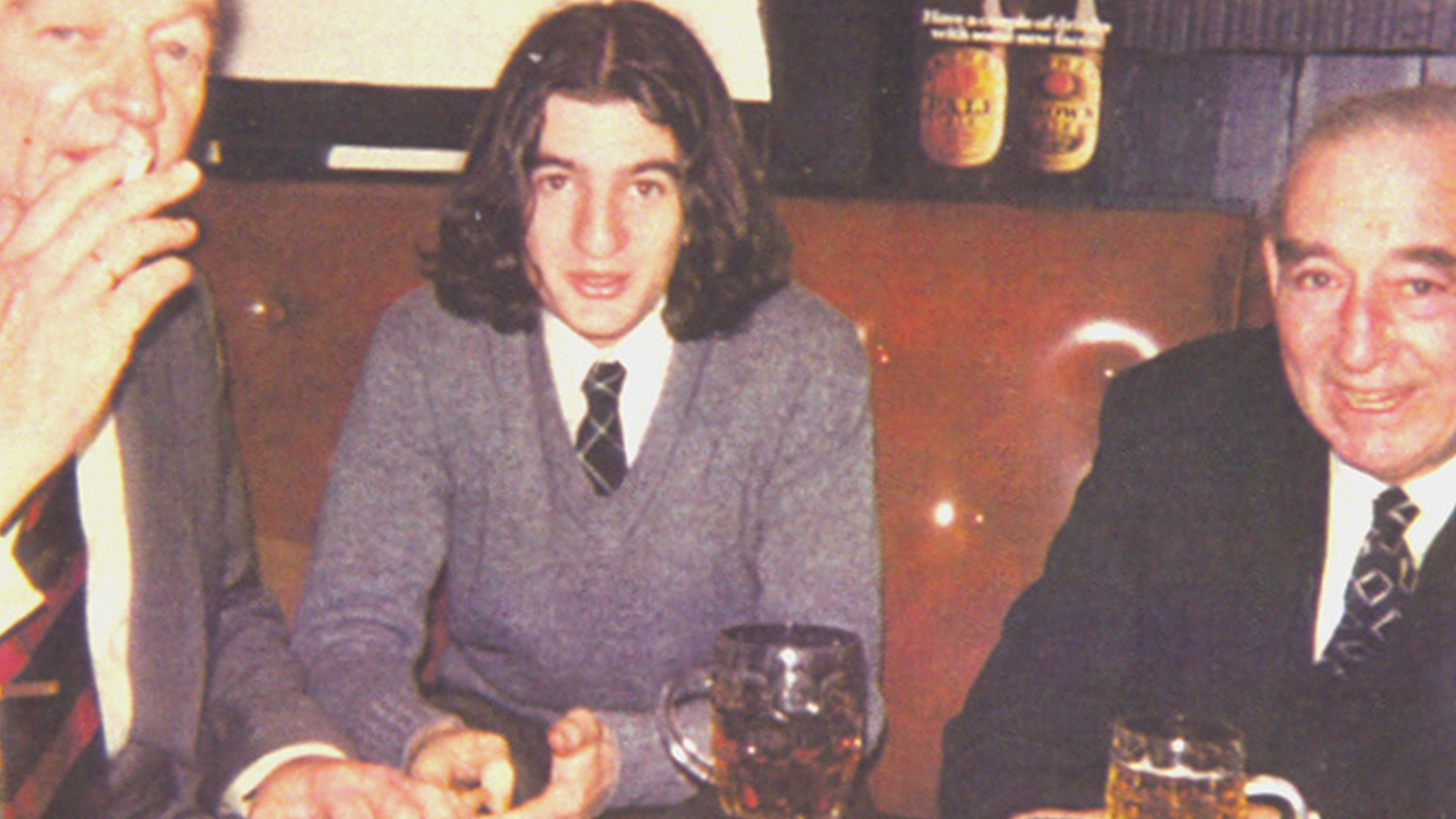

His forebears on the paternal side, many of them namesakes, enjoyed military careers and reputations. His father Geoffrey, an Englishman, had participated in missions in India. After having completed his primary education in horizontal schools, to which he had access not because of social privilege but because he was the son of the English teacher, Charlie enrolled in the Liceo Naval Almirante Guillermo Brown, which, at the beginning of the seventies, was considered a prestigious secondary school. At first, the military likeness suited him well: the slicked-back hair, the lead-gray coat, the pastel shirt, the epaulets, which he donned every Monday of 1974, when he took a train from Constitución to Río Santiago, an island near the city of La Plata, to remain until Friday as a pupil. On his free weekends, he would collect his friend, the renowned musician Andrés Calamaro, who lived on Basavilbaso Street, and together they’d visit some antique stands at the San Telmo Market. They shared a predilection for military coats of arms; they’d feel the military overcoats and try on gas masks. They scarcely had enough money to buy a piece of equipment or an old edition of bilingual poetry. When I visited Feiling’s last library, still intact in 2019, for the purpose of filming it, among copies of Joyce, Beckett, Flannery O’Connor, Latin poets, and Peanuts, I found a grenade that I imagined came from that era.

Feiling attended high school between 1974 and 1978—that is, between Estela Martínez de Perón’s government and her overthrow and the first two years of the military dictatorship, perhaps the bloodiest in terms of torture, deaths, and disappearances. Traditionally, when a group finished its last year of study, it would publish the magazine Proa al mar. Feiling was in charge of the dossier of the twenty-seventh graduating class, although it was listed as “acephalous.” The contents revisited the quick march of their time on the island, its codes, the bond between classmates from a mordant and reflexive point of view. Something about the issue must have been problematic, the “offense,” as the copies in circulation were seized by the military authorities and struck through with black ink.

Double the risk

Feiling’s attitude during his stay in Río Santiago changed drastically. This is attested to in El agua electrizada by one of its early scenes: Tony sees his former companions at the wake and is completely disgusted. Later he describes it: “It occurred to him—with shock and surprise—that the difficulty of maintaining those differences led to his own guilt, the disgust he felt for having been at the Liceo Naval.” A distance that grew stronger with the arrival of the Military Junta to power, a personal affront as he imagined that on the island itself there had been tortures and disappearances. “There are corpses,” Charlie told his mother, according to his last romantic partner, Gabriela Esquivada, paraphrasing Néstor Perlongher’s poem. In fact, two writers who graduated from the Liceo, Juan Duizeide and Daniel Ortiz, recall it in the magazine Lucha Armada (2011): there were more than a few insurrectionists who fell during that period, given that “the repressive forces were especially merciless with the graduates of the Liceo Naval, whom the armed intelligence services always kept in their sight.”

In Feiling’s library I found a medical leave request from 1978. Moreover, I found a photo of a visit by Emilio Eduardo Massera, a member of the military Junta before his retirement that same year, and I didn’t see Charlie in the row with the cadets. Strictly speaking, the coincidence of dates is not definitive, but it’s still a confluence that reflects that Feiling didn’t want to lay eyes on “Commander Zero,” a means to escape from that bubble. Or perhaps he could have hidden in what was colloquially called the “bita” (the bitt), a place hidden behind the sports locker room with a view of the naval school and the Río Santiago shipyard, where he’d go to rest and smoke out of sight of his superiors. In fact, in the biographies of the graduating cadets that appeared in Proa al mar, written by the young men themselves, Feiling was described as someone swimming in unfiltered cigarettes—his fingers already stained with nicotine at the age of seventeen—but at the same time as affable and a superb reader capable of initiating philosophical discussions with great consistency. “Charlie,” writes his classmate Iván Pittaluga, “you were always willing (when you weren’t plastered), to help out and lend us a hand, so let’s hope you’re able to survive. Just in case, we anticipate burying you in a huge ‘Camel’ box.”

In El agua electrizada, Tony combines the usual hangovers, the tessitura of an academic in retreat, an unbridled diplomacy in his courtships or hookups—especially with El Indio’s sister—and the obstinate need to solve the case. The pace of the novel gains as a Stevenson-influenced adventure, a peripeteia linked to P.D. James and, at the same time, a sort of spy story. This subtlety is demonstrated on two levels: on the one hand, in the inserts with which Feiling cuts, fragments, or shreds the narrative’s temporal style, with phrases in English from Eliott’s poems, or in Latin, from his favorite poets, such as Horace or Catullus, even including the use of the tango-infused Lunfardo dialect:

Mors aequo pulsat. Pallida mors. Pede pauperum tabernas regumque turres, encima.1 Non, Toquate, genuns, non te facundia. Non te restituet pietas.2 Este mundo, república del viento / que tiene por monarca un accidente:3 for those who required greater proof of poverty, there always remained the final demonstration. Death, justifiabily [sic] proud. He used the bombilla to peel off the leaves that were stuck, stubbornly, to the walls of the container. Then he moved on to the Brazilian rhythm of the cup against the heel. A characteristic human activity, producing garbage.

Moreover, the novel explores the repercussions of the splinters of the civilian-military dictatorship, which, at that time, in the midst of the government of Ricardo Alfonsín, gained relevance: it is worth remembering, succinctly and simply, that it is a context of institutional crisis in which the president enacted the Punto Final and Obediencia Debida laws, that is, the end of the investigation and prosecution of those responsible for the forced disappearance of people, and the rejection of the presumption of guilt toward those subordinates who acted under the orders of their superiors. Previously, during the Holy Week of 1987, a group of military men—“los carapintadas” (the painted faces)—had revolted to seek a “political solution” to the trials for crimes against humanity initiated in 1985. “The violence of Argentine political life obliges individuals to place themselves in absolutely strange places and beyond all relevance. It is enough to review the history of Argentina’s great intellectuals to see the scope of that violence,” Feiling told Guillermo Saavedra in an interview in 1992, a way of condensing the entire environment surrounding his debut novel.

More than a trip

Towards the end, Tony attempts to solve the surrounding enigmas with urgency. An upcoming trip to England motivates him: to return to his origins or to take up unfinished business, to go work there as a professor. In her essay Black out, María Moreno sketches an accurate profile of Feiling, mainly based on shared benders and their relationship to England. In 1982, in the midst of the Malvinas War, Feiling is summoned “to the front” to act as a translator. “They didn’t pay attention to his blood,” Moreno writes; nothing was made of the fact that, just at that moment, a “pre-selection” physical had detected leukemia. “Charlie became Argentine because he represented a metaphor of national literature, the Homeland as a sick organism, but which Homeland?” she ponders. His English blood, which so identified and shaped him, with his parents and his initiatory readings, at some point also condemned him. “It is tragic, but at the same time metaphorical,” Andrés Calamaro told me, describing him as a plebeian aristocrat, daring, libertine, in a mold similar to Francis Bacon. It was the waiter of the La Paz bar, an essential enclave in Buenos Aires’s vernacular cultural history, closed during the COVID pandemic, who informed him of his friend’s illness. An extremely powerful metaphor. The fact is, in English pubs or in the Buenos Aires bars, Feiling spent his last years defiantly untethered, not caring about his blood disorder or his surroundings, to establish himself in a few years as one of the most refined writers in the Argentine tradition.

Translated by George Henson