Eduardo del Río-Rius, one of the most prominent Mexican caricaturists, died on August 8, 2017. Author of hundreds of books and comics, and a winner of the National Price for Journalism in Mexico, he left behind a strong legacy of political mockery and an intellectual space for critical thinking.

Best known by his pen name, Rius, he was a self-taught cartoonist, an informal teacher of thousands and a legend of his time. After sixty years of mocking the church, politicians, imperialists, and even carnivores, he established a model of political humor which turned into its own genre. His friends and disciples are the leaders of the Boom of Mexican graphic narrative of the 21st century – prominent caricaturists like Boligán, Helio Flores, el Frisgón, Helguera, and the star of sci-fi and graphic novels Bernardo Fernández Bef, among others.

Now, I must confess that I am writing this—Rius for (absolute) beginners—being largely a beginner myself, coming from a country far, far away from Mexico, I did not grow up reading Marx for beginners instead of my history textbook, nor did my parents read La Jornada every morning. Being a beginner at Rius largely means being a beginner at Mexican cultural life. His work is present on the pages of all important newspapers in Mexico, on both political spectrums. Ruis’s autobiographical book My Confusions, Forgetful Memories is in many senses a book about everyone else’s life but his. His journey takes us back to the moments when Diego Rivera was painting murals at the National Palace. The stories surrounding Rius’s life form a biography of cultural and political life in contemporary Mexico.

Rius’s early days in Mexico City as an immigrant from Zamora look like a scene from A Contract With God by Will Eisner: a young Jewish boy growing up in the tenements, las vecindades in this case, where immigrants from different places share the same poverty in their overcrowded apartments with paper walls. Yet, if Eisner’s story is solemn and heartbreaking, Rius’s is a burlesque tragicomedy. Before becoming Rius, Eduardo del Río was a schoolboy at a seminary of the Salesian order because they at least provided free food and clothes. One of the many contradictions in his life is that, as a caricaturist, he would publish more than twenty atheistic books. He started out working as a secretary, packer, soap salesman, office boy, and accountant at a funeral home, but it wouldn’t be Rius’s story if there wasn’t a comical coincidence even at the morgue, which happened to be side-by-side with the best used-bookstore in Mexico City. The Bookstore Duarte was a common meet-up spot for prolific writers, including José Agustín, Carlos Fuentes, and Carlos Monsiváis. Rius killed time at his job by reading, solving puzzles and teaching himself how to draw – another moment of dark comedy, given that one of the mournful clients happened to be Francisco Patiño, a director of the popular humorous magazine Ja-Já. Patiño noticed the boy’s doodles and offered to pay for some, and a week later five of them were published. “Silent humor, by Rius” appeared in October 1954, and this is how the phenomena called Rius was born, as he would say, “by dumb luck and without wanting to want it.”

Rius quickly took sharp anti-religious and leftist political stances, which even got him excommunicated by the church due to his collaborating with the magazine Siempre!. In the sixties, he started directing the humor supplement El Mitote Ilustrado in the journal Sucesos, previously directed by Gabriel García Marquez. The supplement became a collaborative space for many of the active cartoonists at the time, like Alberto Isaac, Abel Quezada, Héctor Ramírez Ram, and Alberto Huici, founder of the Cartoonist Club of Mexico. While directing the El Mitote Ilustrado, Rius had a significant role in mentoring Rogelio Naranjo Ureña, a friendship that lasted until Naranjo’s death in 2016.

In 1965, Rius started publishing the comic series Los Supermachos, a legendary political mockery. The series became an instant hit, selling 25,000 copies weekly. Although considered frequently as the first political comic in Mexico, Los Supermachos kept a popular profile – the simple and effortless lines identify characters from everyday life with precision. It is not humor for the elite reader, but colloquial comic relief amongst the complexity of political pressures. These characters are archetypes from El Barrio Merced, where Rius grew up “surrounded by little whores, doorkeepers, scammers, pachucos, beggars, sellers of caged birds, and old pious women.” He transformed people he encountered into immortal characters, like his aunt Angelita, who will forever live on as la tía Eme in Los Supermachos.

After Los Supermachos was censured, he felt further encouraged and went on to produce another classic – the series Los Agachados, which dealt with Mexican history since the Spanish conquest. After the events surrounding the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968, Rius joined forces with Helio Flores, AB, and Naranjo to establish the magazine La Garrapata as an effort to defend the student movement. In 1969, he was kidnapped by the military due to his social activism and pro-communist stances. Yet Rius never gave up on political humor as criticism, which turned into its own genre. He kept cultivating this genre until he started hating it (or at least that was what he claimed).

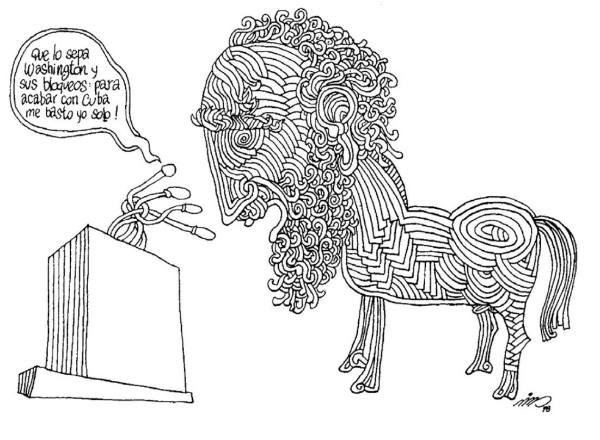

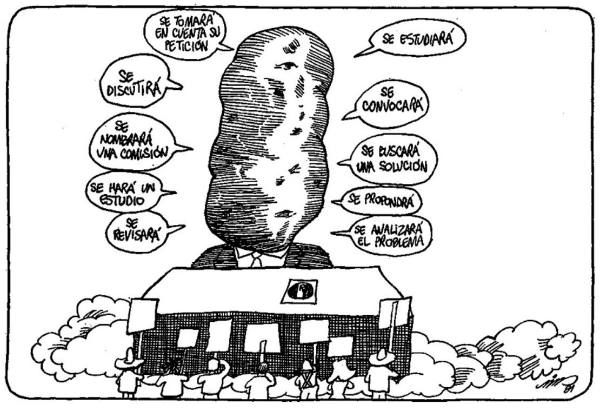

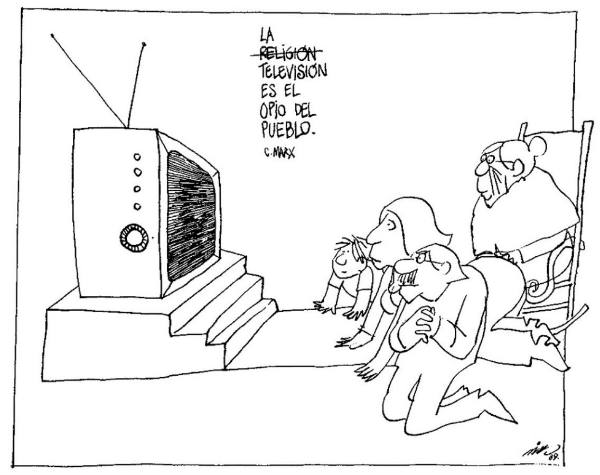

He had a talent for humanizing (and humorizing) even the most complex of topics, bringing them closer in a didactic, yet not necessarily pedagogical way. The writer Carlos Monsiváis used to say that there are three departments of education in Mexico: the Secretariat of Public Education, the media conglomerate Televisa, and Rius. His education was based on liberalism, acceptance, and open thinking. He published more than a hundred books on religion, philosophy, politics, economy, feminism, social issues, and even end-of-the-world theories, vegetarianism, and human stupidity. The most famous are his first pro-communist books of the series “for beginners”—Marx for beginners and Cuba for beginners—although he would later offer various forms of criticism of the Soviet Union and Castro’s Cuba. He will be remembered as one of the strongest critics of American imperialism, capitalism, and corruption.

Rius is a decisive element in the continuation of a strong tradition of graphic narrative in Mexico. He left behind a defined genre of political humor, several specialized reviews like El Chamuco, and a super-creative generation of cartoonists, illustrators, writers, and journalists. He is a teacher of words and drawings that question, criticize, invite, teach, and, more than anything, give us space to catch some breath. Thank you for everything, Rius!

P.S. I bet he you would answer all of this with the same line he said to Bef when they first met in 1992: “I chose to do this by reading your books” —“And what do I have to do with it, bro?”

Radmila Stefkova

University of California, Santa Barbara

Gallery: Drawings by Rius