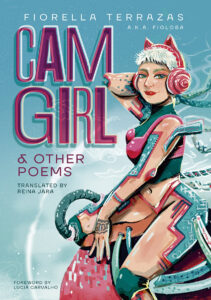

Peru: Dulzorada Press. 2021. 262 pages.

Throughout time, poetry has undergone changes regarding its primordial element: the word. Just to refer to the poetic text, the poem first abandoned an ancient dependence on rhythm and metrical structures. And then, with free verse, its attachment to the silence of the page (a necessary element for the creation of symbols) was accentuated. Poetry then “spoke” by means of silence, not of literality. The words were arranged on the page so that silence was more powerful than the literal sense. What has happened now in the age of communication technologies?

Throughout time, poetry has undergone changes regarding its primordial element: the word. Just to refer to the poetic text, the poem first abandoned an ancient dependence on rhythm and metrical structures. And then, with free verse, its attachment to the silence of the page (a necessary element for the creation of symbols) was accentuated. Poetry then “spoke” by means of silence, not of literality. The words were arranged on the page so that silence was more powerful than the literal sense. What has happened now in the age of communication technologies?

When we say that poetry is language, we are not only referring to a verbal structure detached from a social environment. The poet today communicates live and direct with the “reader,” the one interacting with the other in an ivory tower collapsed by the internet, through social networks and virtuality. There is no mystical emptiness, there is no more silence with symbolic meaning. What’s more, there is a distrust in meaning. That is why, today, poetry tries to say it all (poetry of knowledge?), to encompass everything (sense and countersense, in verse and prose…) and that is what we see in Cam Girl & Other Poems, by Fiorella Terrazas (Lima, 1990), where we read the voice of a young poet in the process of constructing a new discourse: the voice of an I-(an)other.

In the first section, Inanición / Starvation, the affliction of the self facing the voracious machinery of the city that annihilates the poet’s heart not only becomes the song of a wounded voice; we also glimpse a proposal: “I have decided to die today by starvation. I have no money but I do have a book by Juan Rulfo. Perhaps my microorganisms will create a random chance and from this book a pantheon will be born where my guts will go to die.” It is a self-immolation, but one that leads to transcendence. The reference to Rulfo is not an attempt to configure a common cultural identity, but to open a path that transcends all national data or a bureaucratic self on an ID card. The human is now—and more so in times of pandemic—the awareness of being composed of microorganisms; of not being a purified being.

“He has just blown his nose in plain sight of the teenagers./ His tears spill the absence of a self to save him.” In the absence of that “self,” different “I’s” are rehearsed, feminine or masculine, in first, second or third person: “I devise my bed/ of macabre man/ of 23 personalities.” It is a he or she or a we without an I, who observes, who witnesses, who verifies, who gets sick, who gets hurt. And what they see is what they feel, and what they feel is what they see or dream or imagine or create. In a world or social machine that divides beings into winners and losers, where “the social instinct no longer reproduces.” That social instinct is called solidarity. This is why the poetic voice, on account of this absence, will create a community of feelings to empower each other and themselves: “I think of feelings and invent disobediences,” they say along with the redefinitions of new identities to make the change effective: “the dehumanized body sticking its head between the walls/ seeking for a new will.”

In Power, the second section, the language gradually concentrates, but at the same time becomes more fluid, something that will be better appreciated in the third section. The harmonic musicality of the first part gives way to another type of rhythm, more fragmented and, in turn, more connected to (or embedded in) the sensibility of the self. Here is where this “will” activates and assumes a politics of action, not of discourse: “feeling like a little piece of the world/ I am a little piece of this legion/ that shouts / JUSTICE AND REPARATIONS.” Long gone are the times when the poet claimed to be the voice of the people, with a beautiful and hopeful discourse of change towards a better future. The poet describes this social and political action from her verbal apparatus under construction: “but I am also a school of fish, forming another school of fish/ of free beings who swim,/ full of courage/ we are the sea,/ swallowing the sky and the silence.” The poet speaks to us from the real place she inhabits; it is not that she only exists or wants to define herself from the virtuality of an ephemeral reality full of pleasure and punishment: “and (we) will be peace-filled tears in a country where we’ve already lost it all,” she tells us, overcoming the Peruvian disenchantment with the failure of traditional politics. And, to be sure, even by criticizing virtual language, this hyper-awareness leads us to realize that “this world is no longer a meme.”

The collective approach does not make the poetic voice lose its singularity; the self constantly returns to reaffirm itself as a new subject: “so I wash my hands as a symbol of purification.” Technology makes it possible to complete the lack, fill the absence, repair the flaw: “virtual reality doesn’t last as long as this dream,/ no more than a book in a temple of shamans/ so I’ll heal my wounds thus, embroidering organic forms on my chest,” she tells us with the conviction that technology cannot do everything without poetry. The poet is not a passive entity among the technological, but rather they complement each other: they merge to compose that critical self, social and insular at the same time.

In the third and last section, Poe Futuro / Poe Future, a generational voice is adopted, a sensitive and questioning voice discoursing on different poetic topics that attest to the fact that the old “épater le bourgeois” (to shock the middle-class) no longer has any effect in a world where social and cultural strata are different, or are fluctuating; when paradigms are no longer such. We live in globalization, and even though this book celebrates the possibilities that technology offers us, it is also a step away from that initial fascination it may have caused at one time.

The “I is Another” of Rimbaudian symbolism has derived into the “I is Other/Others.” As we were saying, we no longer write from “silence” but from virtual reality, from knowledge, from science… The real can be a dictatorship, an injustice or a pandemic; but poetry, even with its variants and metamorphoses, is always the possibility of multiple voices that open the way to a more fulfilling future.