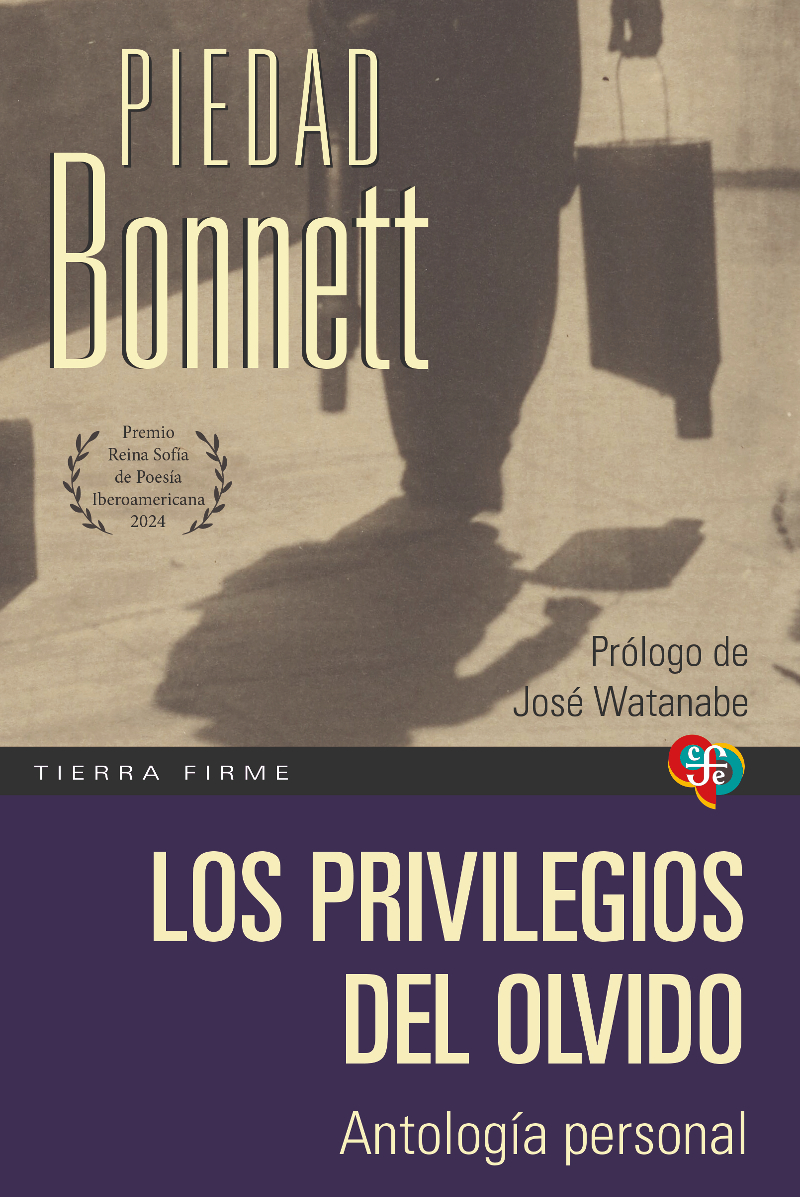

Piedad Bonnett—poet, novelist, playwright, winner of the thirty-third Premio Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana, and one of the most esteemed poetic voices of Colombia and Hispano-America—spoke with us about her new personal anthology. In Los privilegios del olvido (FCE, 2024), Bonnett brings together what she sees as the most outstanding texts of her writing career and continues down the poetic path she has always followed, marked by the unequivocal word and the dark revelation of speech.

Juan Camilo Rincón: You have been a practicing poet for almost forty years. What do you make of your body of work today, in hindsight? How does it feel to return to your own poetry each time an anthology is published?

Piedad Bonnett: I feel I have come full circle. I feel very satisfied with what I have accomplished, because I never thought my poetry would really matter to an audience. For many years, I thought I was writing for myself, and it wouldn’t be of any interest to anyone. So, many years later, to see that this dream has come true—not just the dream of writing poetry, which is what a writer loves the most, the moment of writing, but also the dream of having lots of readers and recognition for this work—makes me very happy.

J.C.R.: Los privilegios del olvido reminds me of personal anthologies like those of Jorge Luis Borges, Gioconda Belli, and Vicente Aleixandre. How was the experience of curating your own work in this way?

P.B.: It is problematic, because it has to do with your state of mind and the self-critical phase in which you find yourself. There are times when you’re excessively self-critical and that makes it very difficult; nothing seems worthy of being in an anthology. But there are other times when you love yourself more, when you’re kinder to yourself, and you even read your own poems like you had never read them before. That’s the challenge of the personal anthology: you can’t work on it continuously because you might lose perspective. I adore personal anthologies because, although I very much appreciate others anthologizing my work, I often don’t agree that they have chosen the best poems, the ones that have to be published. I have a very clear idea of what my readers like, of which poems people love the most, but there are also some that I love, and that I will love eternally, and that, based on my criteria as someone who is able to keep a certain distance from poetry, I believe will last.

J.C.R.: This anthology follows an inverted timeline; it starts with your most recent work and goes back to your earliest publications. Why did you decide to put it together that way?

P.B.: I saw it in another poet’s anthology and it struck me as a wonderful idea. The thing is, you are advancing, attaining things throughout your career as a poet. It’s not that there’s “progress,” but you do keep learning things from the practice. In my first poems, which are from my youth, when I was between eighteen and thirty, I was still learning about poetry, about what I was reading, about my various authors. I did not feel like an established writer—far from it—because I published my first book at the age of thirty-nine. Throughout that time I wrote around two books, but I find it more interesting for people to start at the last moment and look back toward the starting point. It’s a possibility like any other. In the case of the Fondo de Cultura Económica anthology, which was published when I was around sixty, there were some books they omitted from the anthology—the later ones. But I think, at that point, I had already come full circle, as I told you before, and I had made my way to books that are important to me today. I gave it a try, and the readers are the ones who will decide what they feel when they read it that way; they are also free to pick up the book backwards and start reading at the end, like they do in the Far East, from back to front, as we would say.

J.C.R.: Or like Cortázar’s Rayuela, where you can choose the chapter for yourself…

P.B.: That too! Because that’s how you read poetry.

J.C.R.: There are certain subjects and poetic forms that have been fundamental at different periods of your life: solitude, erotic love, childhood… Has writing about these themes changed the way you perceive them, work on them, and read about them?

P.B.: The fact is, a writer writes in said writer’s time, and I am not the same as I was fifty years ago or when I was in my twenties, so everything has changed. My conception of solitude, my conception of childhood too, of course, and my conception of love have all changed tremendously. Life has changed me. Life has put different subjects into my life that were not there in my youth… That’s the nice part about an anthology: you’re not just seeing how you got to grips with a certain language, with poetic language, you’re also seeing how your life has played out, because poetry is profoundly linked to experience. Reading the poems, you can discover the phases through which the poet has passed and the obsessions she has had at any given moment, and you can also come to understand how these obsessions have been left behind. But the most important part is how, at certain times in life, the word changes for you, your poetics change. It’s clear to see in my case. In Las tretas del débil (2004) I have a certain voice, and from that book on I believe my voice changes, not radically—because that can’t happen—but there are elements of life itself that make that voice, I’d say, harder, more concise, even drier. That’s it: a harder and drier voice.

J.C.R.: This is the first book you’ve published after receiving the Premio Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana. How has that changed how you see your work and yourself today?

P.B.: Well, this is a revision of an anthology I prepared a long time ago, so this anthology is coming back to life at a very important moment for me, because I now have an extremely broad readership. When this anthology came out many years ago, I was relatively well known in the poetry world, but now I have a great deal of readers, too many to count, and the FCE’s decision to publish the anthology serves to commemorate that—it’s a sort of homage to the prize I was given, and a reminder to readers that this anthology was always there, but is now within reach of those who have never read me at all. And, the fact is, it’s very interesting to read a poet for the first time through an anthology; that way you really find out if you identify with her poetry, if you love it or not.

J.C.R.: It took you over ten years to make the move from poetry to prose and fiction (Lo que no tiene nombre, La mujer incierta, Donde nadie me espere, El privilegio de la belleza…). Where did that decision come from, and what was it like making that leap?

P.B.: I had always wanted to write novels and short stories, but I attempted to write my first novel when I was in my twenties and it didn’t work out. Luckily, I was self-critical enough to say, “I’m not ready to do this.” And, meanwhile, it turned out that poetry—which had been with me throughout my adolescence and which I started writing much more seriously and responsibly when I was at university—started to flow and come out as a vital need, and because I was troubled by my inability to write fiction. Poetry took fiction’s place and calmed me down for many years because it is my natural language. I don’t know if anyone can say the same of the novel—maybe so—but I can certainly say that I am a poet first and a fiction-writer second. The thing is, I am passionate about narration, and when you write your first novel you get addicted to it, since, besides, it takes you many, many hours. The way you write poetry is very different; it doesn’t demand the continuity of fiction. So, when I already had six or seven books of poetry, suddenly the idea struck me that I could try again. I had taught fiction and poetry for many years at the university, and I had knowledge of many critical elements; I had dealt with poetic structures, points of view, narrative forms; I then had a much more critical approach to the novel, a deeper approach, and perhaps I was more conscious of the possible skills you need to write fiction. So I threw myself into it, and luckily poetry never left me behind. But, of course, you have to space it out, because you can’t work in two genres in the same way, with the same intensity, at the same time. Poetry books have come into being while I’m writing prose. My last three were with the Visor collection in Spain, and now I’m about to put out a fourth with them, but I don’t know exactly how many poetry books I’ve written; to be honest, I don’t keep count.

J.C.R.: What is your upcoming book with Visor?

P.B.: It’s called Los hombres de mi vida, and it’s a book I started writing two years ago, but I haven’t been writing it that whole time; I’ve been working on it very slowly, and I’ve written other things in the meantime.

J.C.R.: You have written about complex topics like corrupted bodies, unidealized families, worn-down couples… How do you decide which form of writing will best allow you to address these topics?

P.B.: I generally write about the same subjects, in prose as well as poetry. For example, I have two poetry books about childhood: El hilo de los días (1995), which won me the Premio Nacional de Poesía a great many years ago, and then I returned to the same themes in Las tretas del débil, because I had not yet come to terms with the subject of childhood. But it’s also the focus of my novel El prestigio de la belleza (2010). A novel demands that you tell a story; poetry demands something else. Poetry illuminates moments and has a very different intensity, and although poetry certainly tells stories—because it is able to do so, and, in fact, my poetry is quite narrative—it does so completely differently; it requires a completely different handling of language. What comes to me is the idea of the poem. We writers must have tremendous intuition to know: this must be a poem, that must be a novel. I can’t get it wrong. I feel myself in the poem’s language and intensity, and suddenly a story comes to me, and I say: this story deserves to be told, like Daniel’s. After his suicide, I thought poetry would come out because poetry is much more closely linked to feelings, to sufferings, but no—I had no choice but to tell Daniel’s story. While I was writing Lo que no tiene nombre, which came out in 2013, I was very slowly writing the poems of Los habitados, which I published in 2017. So they said, “Why did this take you four years?” Because poetry demands a great deal, and even more so when faced with a subject of that magnitude. I couldn’t come out with a book full of emotionality, of purely personal matters, no. I had to digest it and turn it into poetry of very high quality such that it would live up to Lo que no tiene nombre, on the one hand, but above all such that it would live up to Daniel’s memory.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon

Photo: Colombian writer Piedad Bonnett in Madrid, 2022. By Archivo ABC / Ernesto Agudo.