“Respect for Poetry is a conviction deeply-held, with no loopholes in his work. This joins him with the Spanish poets of ‘27, whose example has been of great value to him”

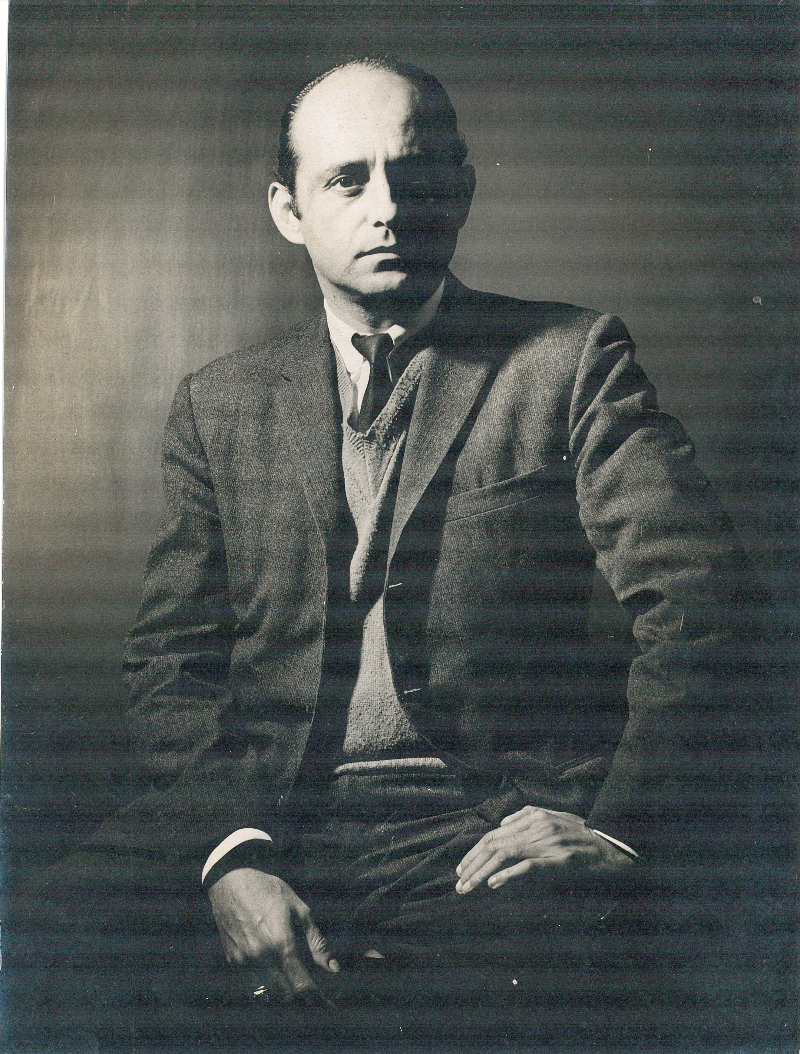

Carlos Germán Belli (Lima, 1927) is, at present, the most significant living poet in Hispano-American literature. He is the last remaining representative of the extraordinary Peruvian generation of ‘45/‘50, translated into many languages, the second most anthologized poet of the twentieth century after César Vallejo (this fact speaks for itself), internationally recognized with prizes and distinctions I will not take the time to name… His sweeping poetic career has shown facets so personal and yet so universal as to have set him apart like few others within the shared literary panorama of the Spanish language.

His unmistakable voice emerged powerfully in Poemas (1958) and Dentro & fuera (1960), breaking with the schemas and trends of the moment, binding a dedication to form and avant-garde experimentation together with social feeling. In 1961, he published in Lima the first edition of ¡Oh Hada Cibernética!, his most iconic work, made up of twenty poems and illustrated by Fernando de Szyszlo. The next year saw the release of a second, greatly expanded edition, for which he received the National Poetry Prize. The poetic self that comes through in this text sets the standards that would go on to identify his work, although he would also evolve, first nuancing and later overcoming his characteristic negative charge. A “loser” self, as James Higgins defined it, who feels defective and incomplete, as insignificant as an insect, stuttering… A self that suffers and exposes social inequality. His only way out comes in the form of the “Cybernetic Fairy,” whom he invokes like a goddess. She has been the crowning symbol of his poetry ever since, and she is now an icon, having transcended even her creator. By her side, from his first collections on, his closest family members have a striking presence.

His is a self expressed through truly original and innovative forms, with a style—as José Miguel Oviedo put it—that is “literally inimitable.” The social realities of his contemporary Lima are framed in the bucolic stereotypes of the classic lyric poetry of the Renaissance and the Spanish Golden Age, but always linked with modern, colloquial voices and twists of street language. The result, as Paul W. Borgeson has rightly recognized, is a “communicative system” as personal and complex as it is coherent, made up of more than mere rhetorical resources: a way of doing that singled out Belli’s work from the rest of his generation (Francisco José Cruz).

In 1964 he published El pie sobre el cuello, and in 1966 Por el monte abajo. Like before, both books present short compositions, leaning ever further into Mannerist and Baroque stylings—especially those of Francisco de Medrano (1570-1607), a first-rate poet who was and would remain a major reference, and Luis de Góngora, among others. The poetic subject expressed here is one who suffers “a myriad over the course of bodies / of crude and illicit dents”; who is “up to [his] throat” in sorrows and hardships; chained “to the hard stock” of the thousand obligations and commands of the “white masters of Peru,” who watch him “ever mockingly” while he, “tired now to the hilt,” “hiccuping,” breaking into bits and pieces and falling apart, feels he is handicapped—as was his brother Alfonso, a recurring figure in his poems—with no chance of movement or flight. Another of Belli’s unique metaphors is that of the alimentary bolus, which is variously recreated, especially in the verse collection En alabanza del bolo alimenticio (1979). Here, he references matter and his own body, which, being perishable, implicitly bears the burden of death. A body that feels inferior even to the food it ingests; thus, for example, in “Penas de un bolo alimenticio por su descontentadiza presa de carne en una fría mañana del siglo XIV,” a mouthful of high-quality meat feels angry and ashamed at being in his company. With style and metrical techniques proper to the lyric poetry of the troubadours, in continual contrast with present-day parlance, he achieves an absolutely masterful ironic, humorous, and pointed effect. Another of the “gods” completing this satirical allegory with which to decry his situation and that of many others is “Ficso,” whom he must serve, not receiving as much as “some charred crumbs” in return. Fisco is the supreme representation of the economic forces that govern the world. This is, without a doubt, a wondrous combination of bucolic and pastoral poetry—with mythical beings, characters named Filis, Anfistro, Marcio, etc.—with the reality closest at hand. Through irony, the grotesque, and a touch of black humor, he assembles a lyric universe of surprising contrasts.

Previously, in Santiago de Chile, he had published Sextinas y otros poemas (1970), lending the book’s very title the name of the closed-in composition, coined by medieval Provenzal poet Arnaut Daniel, that Belli recuperated for Spanish-language poetry with his “Sextina primera” (El pie sobre el cuello) after more than a century (later, Jaime Gil de Biedma would do the same in Spain). Along with the sestina, Belli would incorporate other strophic poems into his work—like the villanelle, the ballad, and the Petrarchan canzone—which would become favored molds in his poetics.

“BELLI TAKES ON WRITING AS A CHALLENGE, A CONTINUAL CONQUEST; IN HIS POEMS, HE PROVOKES A TENSION THAT EMERGES FROM AN ENDLESS URGE TO OVERCOME, TO ATTAIN WHAT IS SEEN AS SUBLIME AND HAS IMMEASURABLE VALUE FOR THE SPIRIT”

In reference to the period from 1958 to the late eighties, Jorge Cornejo Polar speaks of “a long remembrance of grievances” that, along with his style marked by such personal facets, makes up a “Bellian space,” defined by Belli himself as “a sort of combinatorial art, perhaps resembling the processes of alchemy.” This image aligns nicely with Belli’s tastes—after all, his mother was a pharmacist and he was raised in a drugstore, which adds up in reference to a process of transmuting matter in which a series of elements transform in their primary qualities, producing other, new elements of greater value. Along the same lines, Mario Vargas Llosa claims Belli was able “to turn the ugly into the beautiful, the sad into the stimulating, and what he touches—poetry, that is—into gold.”

The eighties were equally fruitful for Belli. He published Canciones y otros poemas (1982), El buen mudar (1986 and an extended edition in 1987), Más que señora humana (1986; published in Mexico in 1990 as Bajo el sol de la medianoche rojo), and En el restante tiempo terrenal (1988 and an extended edition in 1990). These verse collections grow ever less acid in their irony, taking on a more reflexive and hopeful tone and a more metaphysical character, just as the compositions themselves grow longer and more complex. This change corresponds to changes in the poet’s life, as if his conquests of living space and poetic space ran in parallel. The pleasure of poetry swells in his work, showing through in myriad ways, along with love. A love that is not only passion for the beloved nor this passion’s sublimation, but is rather the engine, the drive, and the path towards liberation. From his invocation of the “Cybernetic Fairy,” he moves on now to Hope, a Latin deity and a Christian virtue, whom he salutes in his poem—which would later become a book—¡Salve, Spes! The poet glimpses a new reality that allows him to develop the “humanity” offered by love and the word. We observe this journey in his verse collections from the nineties: En el restante tiempo terrenal (1990) and Acción de gracias (1992). In them we find never-before-expressed joy and acceptance, alongside the inexorable passage of time, which is also very present—a change that also gives way to thankfulness.

All of this—which could be defined, as Martha Canfield put it, as a “dissipated darkness”—flows together in ¡Salve, Spes! (2000), a long song, spilling over emotionally and verbally, in which the poet, at his “wasted age,” sights the midnight sun that breathes life into his hope. His next verse collection, En las hospitalarias estrofas (2002), moves along the same lines, but with a novel theme: the discovery of nature, not as a metaphor but as a space one notices, feeling one’s self-absorption has kept one removed from it. These poems, in general, go back to being brief, returning to the starting point to which the poet now turns his attention. Meanwhile, he continues experimenting with form and playing with rhyme. La miscelánea íntima (2003) and El alternado paso de los hados (2006) are cut from the same cloth—in them, language seems to have been relinquished, to have taken on a greater serenity. The perception of a long road already traveled, the proximity of old age, and the awareness of death are ever more present.

In the poet’s own words, he first came to poetry as a “means of survival.” It would then become a “path of metaphysical transcendence,” expressed as it was for the mystics through the language of love, with the allegory of the “marriage of letter and pen.” Although, in spite of it all, the unending dissatisfaction at not having reached “the inaccessible,” at deeming oneself “an expert at nothing,” does not disappear—this feeling permeates his entire body of work. El alternado paso de los hados closes with an epilogue (obligatory reading) titled “Asir la forma que se va,” in which he reflects on his own writing.

With this long stretch of road behind him, in 2007 Belli published a compilation of Sextinas, villanelas y baladas while, in parallel, numerous anthologies of his work were underway, culminating with the 2008 release of Los versos juntos. 1946-2008: Poesía completa, with a prologue by Vargas Llosa.

His next book, Los dioses domésticos y otras páginas, would not appear until 2012. In August of 2006, a tragic accident ended the life of his daughter, Mariella, not yet a year after the September 2005 death of his dear brother Alfonso. This book is an homage to all his loved ones. Finally, his most recent title to date is Entre cielo y suelo (2016), which maintains continuity with the rest of his work, situating itself in his “prolonged and wasted life.” But the author does not look back with nostalgia; on the contrary, he takes on his setbacks, casting an ever-uneasy gaze of questioning and expectation upon his surroundings. This gaze allows him to reclaim the raw material of his delicate musings, which, for all their profundity, do not leave behind the intelligent irony so definitive of his poetic practice.

Belli’s peculiar language has been studied from various angles: his taste for the baroque, in syntax as much as vocabulary, offset by his contraposition of utterly contemporary expressions and modes; the coexistence of cultured, archaizing language with the colloquial, with words from the scientific lexicon, Peruvianisms, and even vulgar terms, amalgamating opposing elements, brought together in perfect integration. It is crucial to note that this baroque bent is not encoded uniquely in Belli’s style; rather, it contributes also to the plane of meaning, firstly through its irony and secondly through its connotative contrast with the bucolic idealism the poet “recreates,” thereby serving as a jarring wake-up call.

Belli takes on writing as a challenge, a continual conquest; in his poems, he provokes a tension that emerges from an endless urge to overcome, to attain what is seen as sublime and has immeasurable value for the spirit. This is the state of Belli’s struggle with the word; this angst to grab onto it, hold it down, weigh it, experiment with it as if it were a chemical element destined, in the mortar of its personal and worldly circumstances, for an alchemy that will transform it into a new compound whose constitutive elements cannot then be separated. Belli himself, from his poetic experience, emphasizes his ongoing “longing” to find, “with all the strength of the eyes of the soul,” that “form” he feels is always slipping away from him, that “tiered projection in pursuit of the beyond”; a continuous struggle, a “catharsis of tribulations and earthly terrors,” a “desire to reclaim the lost heavens.” And this combat, in and of itself, represents his triumph—the remains left behind on the battlefield are his untarnished poems, the pleasure of their forms, the purity provoked by the impure, the visible rhetoric he puts at the service of the invisible, reaching an unrepeatable, unique solution.

With this objective, Belli chose to swim against the current of the mores and fashions of his contemporaries. Respect for Poetry is a conviction deeply-held, with no loopholes in his work. This joins him with the Spanish poets of ‘27, whose example has been of great value to him. From this conviction grows his profound and powerful verse—of insolent and surprising naturality, as Vargas Llosa described it—which takes its place beyond all precepts (Ricardo González Vigil). We must appreciate his enduring faithfulness to his own work and, beyond it, to Poetry itself. Belli has written because his entire existence has gone into it.

To read Carlos Germán Belli is to read a classic, in the canonical sense of the word: a classic for the future and a classic already, because his poetry has transcended trends and become universal, because he stepped beyond the existing canons of Peruvian and Spanish-language poetry of the second half of the twentieth century, and because, what’s more, he created his own canon within them. When we read him, we witness a renewed valuation of—and a return to—the forms and the aesthetic care of the poem.