STUDY No 1: First principles. Field of observation. Functions.

1. Things exist.

2. Words exist.

3. Words are things.

4. Things are things.

5. The flowers that open their petals to the night exist. They are near the henhouse.

6. Flowers are words and are things.

7. They open their petals. They pronounce themselves.

8. They are under the stars, which are also things and words, and they shine and pronounce themselves.

9. Poetry departs from a function, but not primarily as Jakobson understands the term (poetic function), but rather in a sense that approximates Hjelmslev’s understanding in the realm of linguistics: “[W]e say that there is a function between a class and its components (a chain and its parts, or a paradigm and its members) . . . The terminals of a function we shall call its functives, understanding by a functive an object that has function to other objects. A functive is said to contract its function.” What is crucial in Hjelmslev is that the term function alludes to the word’s etymological sense, and also to mathematical logic: an entity has a dependence on another entity.1

10. Flowers and stars join in the same sentence. You can close your eyes after the period, and only the fragrance remains.

11. Someone transported from another dimension, who appeared for the first time on this planet at this hour and at this spot, knowing nothing about our universe, would be unable to determine whether the fragrance came from the flowers or the stars.

12. The flowers are called buenas noches, or good night. The star is called Sirius, and the stars that form Orion and the Southern Cross also have names.

13. The creature from another dimension has no name.

Jorge, my father-in-law, owns a field that he shares with his brothers. They inherited it from their father, who for his part inherited it from his father, who bought it at the turn of the twentieth century during the period of the French settlement in Pigüé; as such each heir in the line of succession has been left several plots of not many hectares. The field is located in the zone of Cura Malal, partido of Coronel Suárez, province of Buenos Aires.

Whenever we get ready to spend a few days there, my children are happy

I transcribed a memory from this same field at the beginning of volume IV. After my son and I first saw the movie Titanic, we remained in a climate of fascination, boats sinking in our heads, and so, as volume IV states, “after a cold snap we took the barges of ice that had formed in the cows’ trough and shattered them against the chain-link fence while Matías sang the theme song by Celine Dion.”

The gate next to the house opens to a little garden with a tamarisk, a lilac bush, and several buenas noches. Further to the right is a wide space covered with acacias and eucalyptuses. Beneath them, Jorge put up a series of chicken-wire pens to raise hens and roosters. Two-hundred-liter gasoline drums, open on one end and cushioned inside with straw, serve as a nest for some of the hens. When evening falls in summer, there are usually three or four eggs in each.

Between August and October, he chooses the best birds and takes them to the local country fairs.

Gradually, a heterogeneous collection of materials piled up around the cages: rolls of wire, posts and rails to repair the fences, alongside old objects and junk, jars, a few pecked orange and potato peels.

This is our field of observation.

14. Two particles of material become functives. The buenas noches and the cold radiance of the constellations open their petals and contract a dependence or function. They form a system.

15. The creature from the nth dimension is suspended in the middle of the fragrance. It could not enter the system. It’s too small: it was only recently born into the text.

It remains nameless.

It is confused.

STUDY No 2: The coffeepot

I begin my exploration of a delimited area.

I find a brown enameled coffeepot, covered with dust. It is hanging from the chain-link fence that separates the garden from the area belonging to the chickens and the area belonging to the zucchini. It doesn’t look too deteriorated, but I find a small orifice at the base.

There exists a critical moment for dishes, coffeepots, and teakettles made from enameled material, which is that of their first fall, when after washing them, they slip out of carelessness, still wet, from our hands. On crashing against the floor, a little piece of the enamel chips off, and the metal interior is exposed. Nothing can stop the rust that advances there, the cold combustion that reveals itself as orange stains, with a slow, continuous voracity. Each washing of the container eliminates the rust. Cautiously, we dry it clean, especially at its point of injury, and feel satisfied.

But the stain reappears, perhaps from dampness of the environment itself, as invisible as a virus, and it won’t stop until it eats away all of the thin layer of cast iron and leaves, in now terminal cases, a small orifice open from side to side. And then we realize, because it is too late: that moment it slipped from our hands entailed the beginning of the end; the last fall was already present in the first, the one that definitively tosses it into the corner of useless containers.

I have seen some attempts to save dishes by plugging the hole with a bronze solder. They return to use, but a use that one could call diminished, restricted to the intimacy of the family meal. Shortly after the potato stew is finished and the bottom of the pan wiped clean with a piece of bread, the stigmas of an irreversible accident emerge, a golden lump, like a small tumor. The dish has become unpresentable.

This brown coffeepot did not benefit from such an orthopedic treatment. The hole might be no larger than the head of a pin, but is enough for a small puddle of coffee to drip through onto the table.

And now, beneath the rain, sun, and frost, the rust continues its digestion with nothing to stop it, taking ever-larger portions of metal and turning them thin, negligible, finally invisible, an immaterial cancer where particles of dust filter through. The hole now has a diameter of three or four millimeters.

I pick up the coffeepot by its handle and inspect its interior against the afternoon sun; a ray of light filters through its depths and projects a golden circle that comes undone between the weeds, surrounded by a cone of shadow.

Then I decide to raise the receptacle above my head, until it hides the sun.

It produces an eclipse of the face.

In the dark bottom of the coffeepot, I see an incandescent star appear. The same ray of light projected between the little leaves plunges into my right eye. I think the ray could undo it.

16. A function is discovered by looking insistently at an object until the eye secretes a hot and aromatic liquid.

STUDY No 3: The radio

17. My eyes do not have petals, but they open to the things that emerge in the morning.

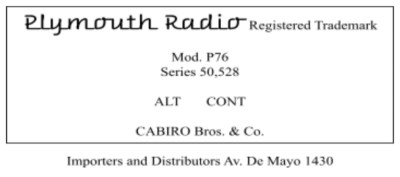

Under the trees, I find a strange electric device tossed under an enameled bathtub, alongside bottles and dented casseroles. The apparatus has a small inscribed nameplate fastened to it with rivets. I read the inscription as a whole, and then I apply the solar coffeepot. Through the small orifice, letter by letter, I read:

All that remains of the radio is the part called the chassis, that is, the metal support with circuits, capacitors, and filters. There is no trace of the speaker or the primitive cabinet or carcase.

A resistor has lost its little wires and been reduced to a small glass tube. The cables mix with stalks and acacia leaves and form an electronic-vegetable network.

Two tubes remain, one coated with burgundy paint, and the other made of clear glass. I point the solar coffeepot toward them, which has revealed itself to be an optical instrument. Through the orifice, the lamp’s interior as an ensemble of threads, plaquettes, and superimposed little plates, much like a space probe navigating a vial, or sailboats encapsulated in a bottle.

Only the glass bases of the other tubes remain.

That radio was rigged to run on batteries, Jorge said when he saw me leaning over the device.

We had a similar radio at home when I was a boy, but it plugged into the 220 volt outlet. You turned on the dial and heard nothing; you had to wait a few seconds until the tubes warmed up enough to overcome the resistance, and then the electrons and music flowed freely. I would lean over the back of the apparatus and see little orange filaments through the ventilation slots, floating in the darkness.

After a while, I’d lean over again, and then a vapor that smelled like mica and reheated copper would come out of the slots.

I return to the apparatus before my eyes.

I note.

Electrons for words.

The latest news launched into the air.

Finally, the little acacia leaves.

I run my hand over the surface of the circuits. They are cold and smell like damp foliage.

The story is a famous one. A group of four young friends, all from well-to-do families in Buenos Aires society, shared the same hobby: they were radio aficionados. One of them, Enrique Susini, was a doctor specializing in the throat and respiratory system. The Navy sent him to Europe shortly after the end of the First World War. He was supposed to analyze the effects of toxic gases.

In France he bought a 5W transmitter that had been used on the front. When he returned to Buenos Aires, he went up to the terrace of a building next to the Teatro Coliseo with his friends and the apparatus. They set up an antenna, placed a microphone on stage, and on August 27, 1920 broadcast Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal. Many historians consider this to be the first program broadcast in the world and consider radio as we know it today to have been born there. From that point the four friends were rechristened “the crazies on the rooftop.”

Our thoughts are inseparable from the metaphors by which we conceptualize them. The next day, an unnamed journalist from the newspaper La Razón wrote this article:

A Concert Raining from the Sky

It is possible that many people are unaware of a simple and, at the same time, marvelous thing. Hidden among the chimneys and ventilation pipes, telephone and electric poles, lie a fair number of radiotelegraphic antennas, sensitive and alert, scattered throughout the houses of the city. They correspond to other such transmitters and receivers of marconigraphic waves, for private use and authorized for all.

Someone had the happy thought to place a powerful microphone in the upper part of the hall of the Coliseo. And last night, a vermicular sound wave undulated through space from 9 p.m. to midnight, as if to cover the whole city with a subtle cloudscape of harmonies of the richest and most fanciful sort, laden with noble feeling.

And for three hours, not only those secret initiates, but those who for reasons of profession or by virtue of coincidence—sailors on ships carrying these apparatuses, radiotelegraphic station operators, all of them slaves to listening—received the gift of Wagner’s masterwork, “Parsifal,” in concert, which was being performed at the aforementioned theater.

Various capitals boast an organization called the “theatrophone,” whose subscribers, through a telephonic apparatus, enjoy musical concerts, conferences, and speeches. Last night’s concert held something more than this: added to the scientific marvel was the moving delight that consists of the thought of those who, without any self-interest, launched into space the full aesthetic treasure contained in Wagner’s score.

Good sowers, they tossed handfuls of feeling into space so that those who were hungry or thirsty might gather it up. And certainly their beneficiaries must have believed these divine notes came down from heaven.

18. Flowers and stars; gaze and circuits; seeds and emotions are the terminals (functives) of a particular function. We designate the (poetic) text that emerges from this (poetic) function a verbal-functional projection.

Translated by Janet Hendrickson

Excerpt from Cuadernos de lengua y literatura: Volúmenes V, VI y VII (Buenos Aires: Eterna Cadencia, 2013)

1 Louis Hjelmslev, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, trans. Francis J. Whitfield (Madison and London: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1961), 33.