What’s hard is to be able to, to be able to as far as possible, to be able to do what can’t be done.

(Sentence found in one of the author’s notebooks in his desk, in his own handwriting)

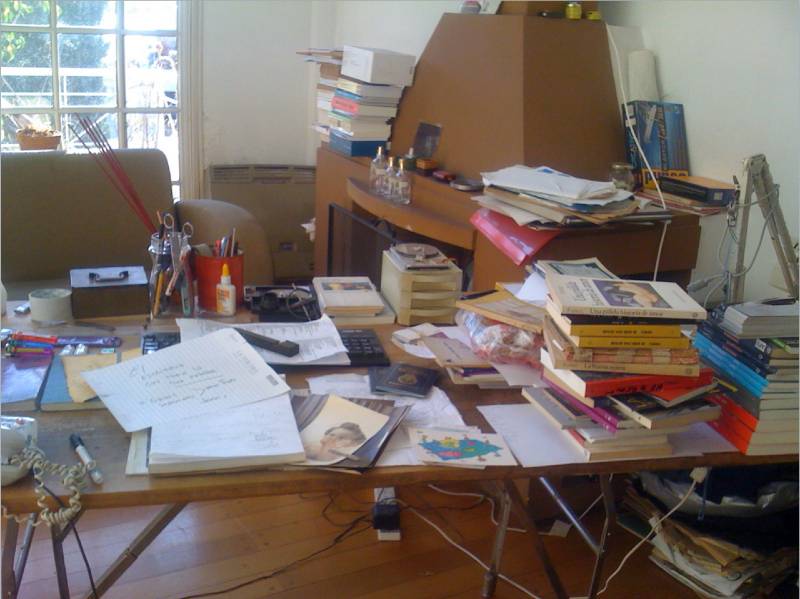

It was in December 2010 that I first set foot in the writer Rodolfo Fogwill’s house. This was in the Palermo neighborhood of Buenos Aires, four blocks from where Jorge Luis Borges once lived. Fogwill’s daughter Vera had asked me to go through the documents her father had left behind, with the aim of beginning to catalogue his archive—his manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, and book collection. At first glance, it looked like a house on hold. There were plants, piles of papers, boxes filled with notebooks, magazines, and press cuttings, photos, ropes, dangling cables, parts for his yacht, as well as several dismantled computers strewn everywhere. Nothing had been touched since the last day Fogwill had been there.

Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill (1941-2010) was born in Bernal, on the outskirts of the city of Buenos Aires. At 23, he graduated in Sociology, after first studying medicine. In tandem with literature, he had a career as a market and advertising researcher. He was the creator of several very popular advertising campaigns for those of us who lived in Argentina in the 70s and 80s, like the one for a tobacco company with the unforgettable slogan, el sabor del encuentro—“the taste of an encounter” (which was later used by the Quilmes brewery) and dozens of little comic strips included in the classic Bazooka chewing gum wrappers. As well as literature, Fogwill enjoyed women, sailing (he even owned a yacht), and being a father (he had five children), so much so that he once proclaimed “fatherhood brings out the best in a man.” He won the Guggenheim award in 2003, and the National Prize for Literature in 2004.

The documents that make up the Fogwill Archive, kept by the author and catalogued by his family, contain everything from his first unpublished poems from the end of the 1960s dedicated to his wife Juana, to the last black Moleskine notebook he had with him in the Italian Hospital where he died. This material offers a way into his world and are some of the elements Fogwill used to construct his work.

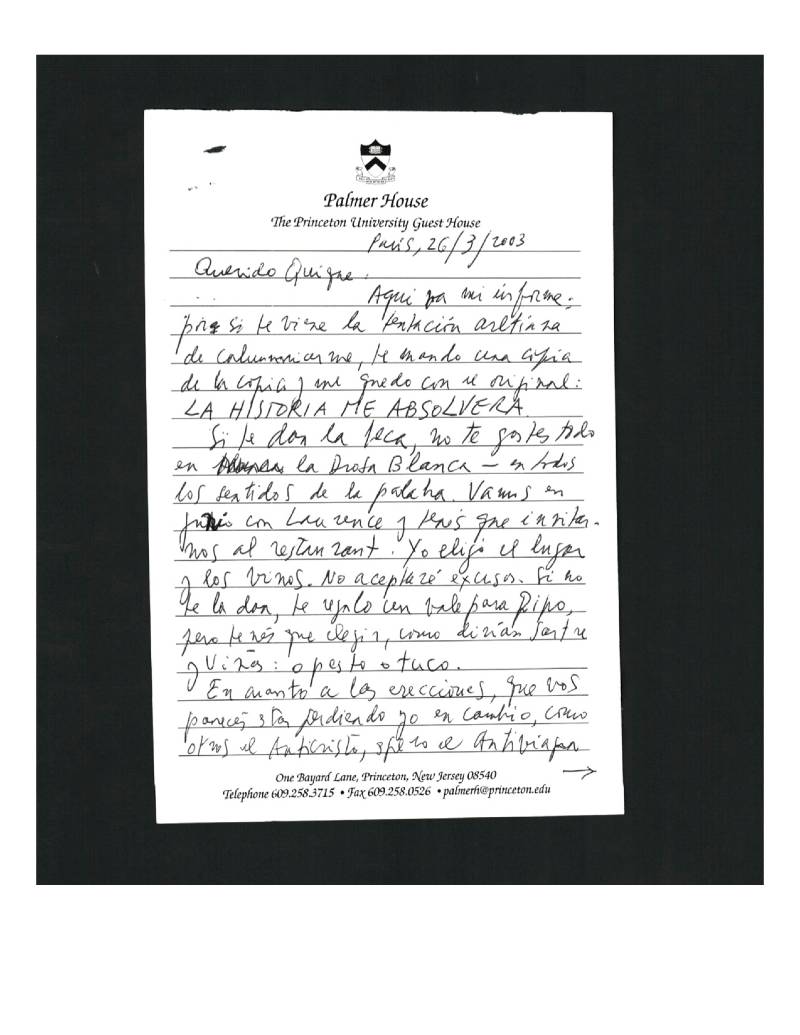

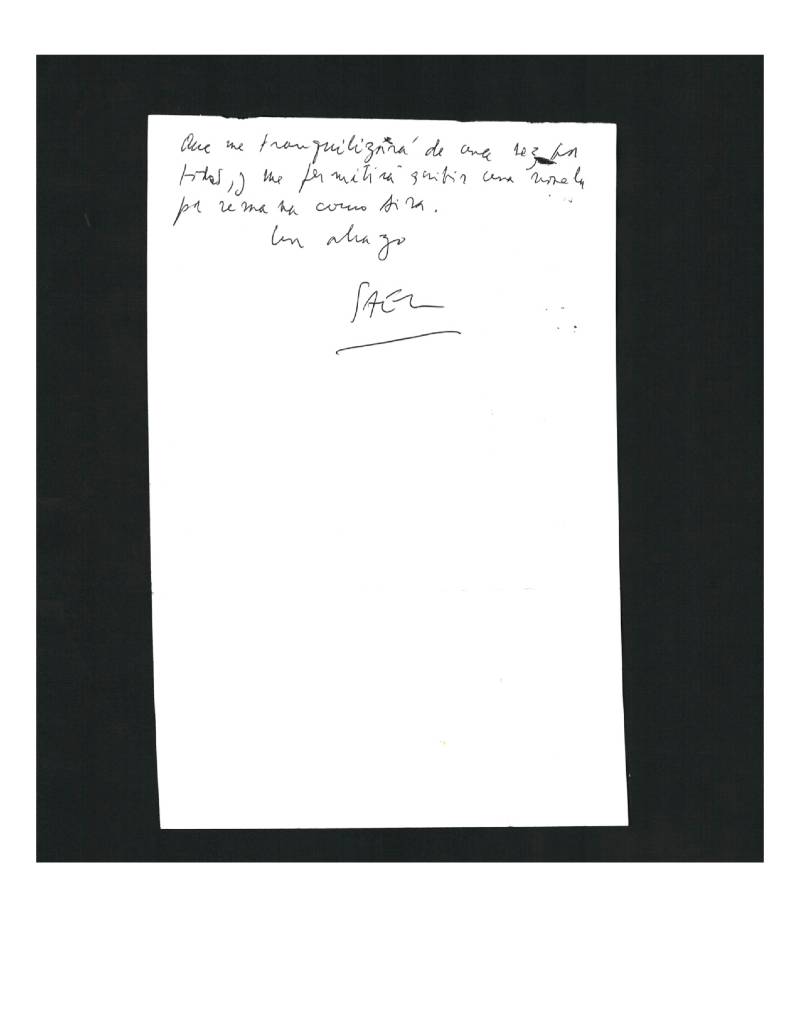

Within the archive, the correspondence is more than a mere chapter in his story. On one of the bookshelves, the author kept a stack of letters from the 1970s to the mid-1980s. Most of them are letters he received from other authors such as Alan Pauls, Osvaldo and Leónidas Lamborghini, Juan José Saer, César Aira, Arturo Carrera, Octavio Armand, Alberto Laiseca, Néstor Perlonger, as well as ones of a private nature. This correspondence illustrates the tenor of his relationships, and covers topics such as the financing of the books brought out by his publishing venture, his views on other writers, the sending of unpublished manuscripts. It is part of a legacy of almost 700 letters that the writer received or sent.

By the start of the 1980s, Fogwill already had two children, Andrés and Vera, a bitter divorce behind him, had set up the market research agency Facta, and Ad Hoc, an advertising agency, but his passion was for literature. He wrote poetry and short stories. Of his poems, the young Alan Pauls, who at the time was working at the Ad Hoc agency, wrote in a letter from November 1979: “There is a lot in your poetry that’s good: above all your way of using different poetic forms, its rhythm and music…”

In 1980, Fogwill won the Coca-Cola short story prize for his story “Mis muertos punk” [My punk dead]. This ended with a campaign against the company over the contract prize-winners were obliged to sign to have their books published. Following an exchange of letters with the company’s External Relations Manager that on Fogwill’s side grew very heated, the writer tore up the publication contract, and received only the cash payment part of the prize. In a fragment of the letter Fogwill sent to Coca-Cola, he wrote provocatively “if a badly written, radical book can win a prize, anyone and everyone could send their originals to the next competition” (letter from Fogwill to Coca-Cola, July 1980).

Concerning this prize, Alan Pauls wrote jokingly to Fogwill: “Coca-Cola refreshes best, but Pepsi is richer” (letter from Alan Pauls to Fogwill, circa 1981).

Fogwill used the prize money to set up the Tierra Baldía publishing house. Here, in addition to his own books El efecto de la realidad [The effect of reality] and Las horas de citar [The quoting hours], he published works by Oscar Steimberg, Leónidas Lamborghini, Osvaldo Lamborghini and Néstor Perlongher. Some of the letters preserved in the Archive relate to the publishing venture. In 1980, Osvaldo Lamborghini wrote to Fogwill: “Last night I re-read the four books published by Tierra Baldía. As a collection, it is perfect. If I didn’t dislike the term, I would say—I do say— that there is a Discourse there. After re-reading them, I felt an incredible rush of energy, and almost frenetically returned to editing one of my own manuscripts” (letter from Osvaldo Lamborghini to Fogwill, 5 August 1980).

In his correspondence with the Cuban writer Octavio Armand, there are references to poets who were not published but were considered as possible candidates, like the poète maudit Jacobo Fijman. Fijman met André Breton in Paris and played a fundamental role in bringing Surrealism to Argentina. His poetry and painting inspired several members of the movement in the Río de la Plata region. “As for Jacobo Fijman… since you were going to publish his poetry, even though it seems you have had to desist, that means you must have some version of it in your possession… I need you to send it to me as a great favour…” (letter from Octavio Armand to Fogwill, 12 June 1980).

Early in 1981, during the last military dictatorship in Argentina, Fogwill spent several months in the Caseros prison near Buenos Aires on charges of fraud and embezzlement. “A lot of military groups targeted advertising agencies and wanted me to team up with them. Whenever one of my adverts appeared on TV, they banned it. In 1980 I did a cigarette commercial. A girl who was at a party leaves with a guy to watch the dawn, and in a panning shot you see she’s wearing a wedding ring. They banned the advert because she was married but wasn’t with her husband. They said I used the dollars I got from advertising revenues to put pressure on TV networks to broadcast coded messages to the guerrillas. They closed my bank accounts, prosecuted me, and put me in jail for six months, accused of fraud and economic subversion” (interview with Leila Guerriero in 2009, published in the cultural supplement of the Spanish newspaper El País, Summer 2010).

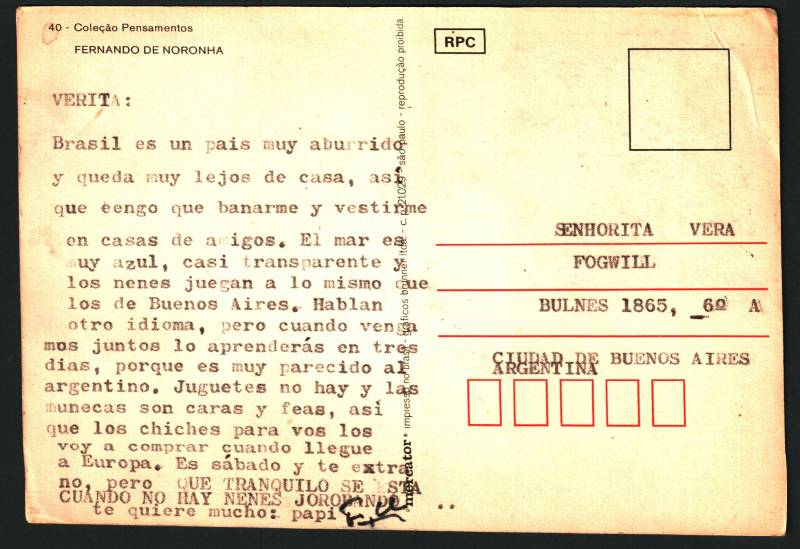

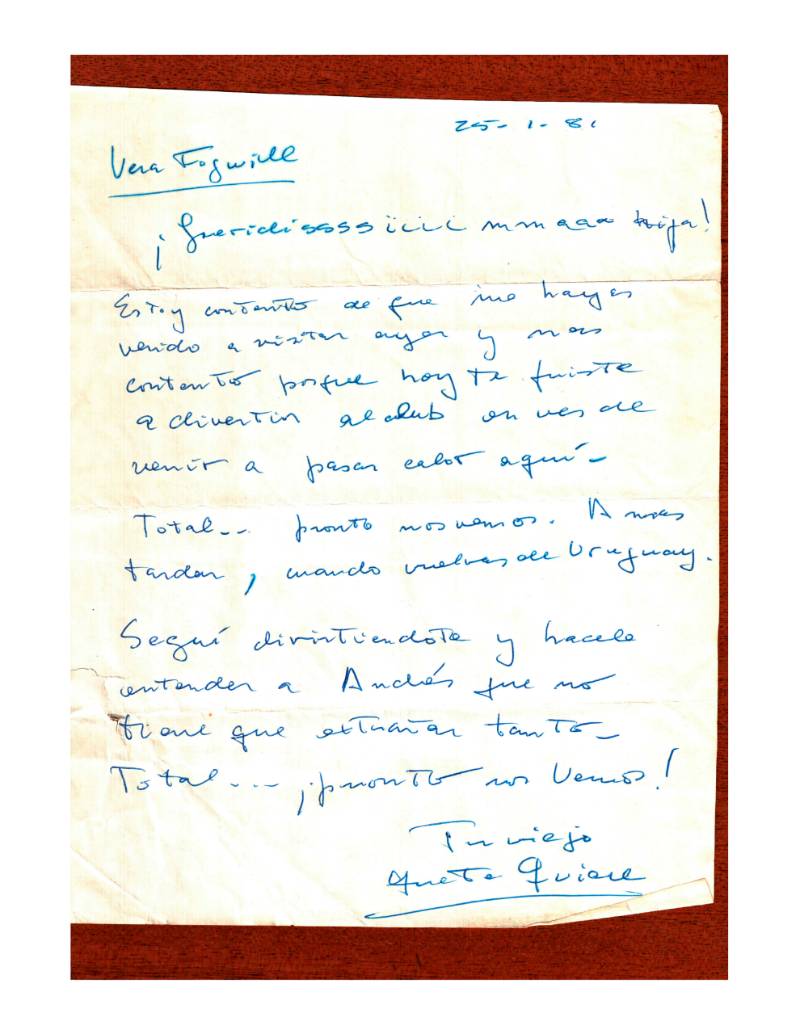

In Issue 49 of the magazine Vigencia in 1981, Fogwill published “El interno que escribe” [The intern who writes], a text referring to his period in prison. In it, Fogwill explains that in jail, the term “interno” [intern] is used for a prisoner. On several occasions, Fogwill writes that in Caseros he used to recite and try to write from memory, because at the start of his sentence he had no paper or pencil. His daughter Vera recalls a visit she made to him with her grandmother Beatriz Pinzoneon on 24 January 1981. “One day she came to fetch me from my house and told me we were going to see my dad. I hadn’t seen him for some time, and thought he was away on a trip to London. I was excited and said to her: ‘Wait a bit and I’ll pack my suitcase.’ She replied that wouldn’t be necessary, and we got into the taxi and arrived quite quickly. I remember we went into a room where there were two benches. Then dad appeared. We started to chat, and he told me he was fine, really happy, and we gave him paper, a pencil, and smokes.” The day after their visit, Fogwill wrote to his daughter: “I’m pleased you came to visit me yesterday, and even more pleased that today you went to have fun at the Club rather than come here and get hot. Anyway… we’ll see each other soon.” (letter from Fogwill to his daughter Vera, 25 January 1981).

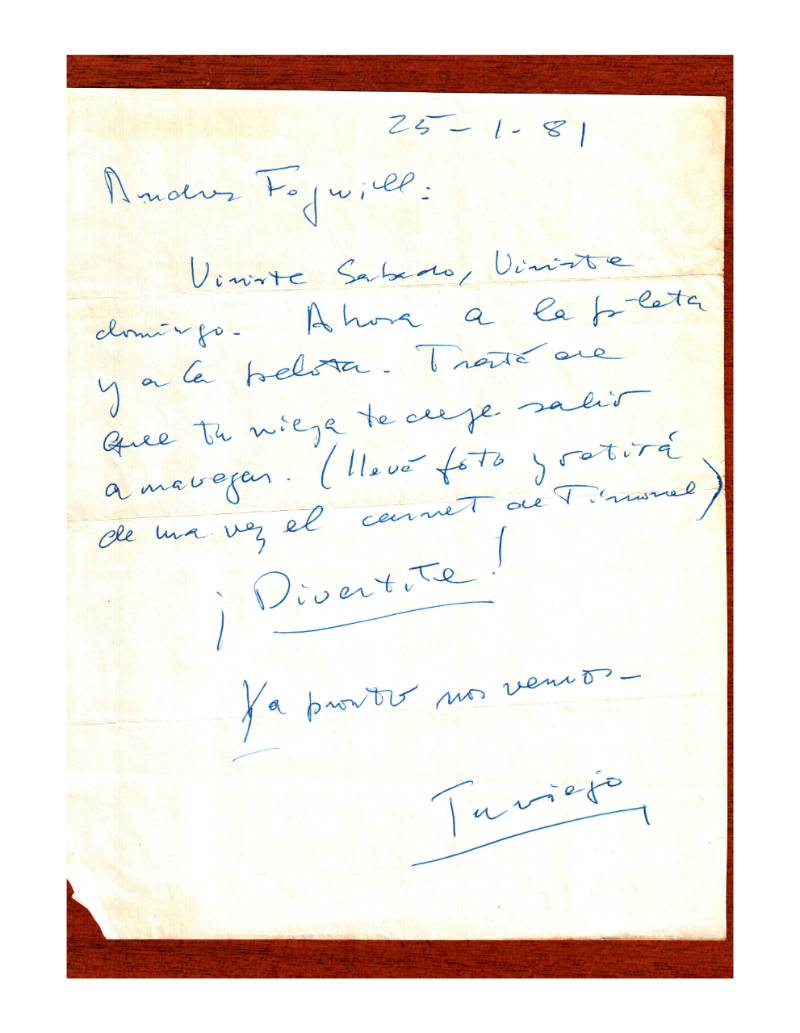

The only letters from his time in prison included in the archive are the ones he wrote to his children. In these he says he spends the day reading, that he receives books, and that “I’m still writing a novel I hope to finish before I get out.” This may be a reference to the novel Nuestro modo de vida [Our way of life], written in 1981, which was thought to be lost, but turned up again during the work on the Archive, and was published in 2014. In his letters, Fogwill asks his children what they are doing for the summer, and advises them to go camping. “The only thing I miss is being with you. But I put up with it, because we’ll soon see each other again” (letter from Fogwill to Andrés and Vera Fogwill, 19 January 1981). Thanks to this correspondence it has been possible to confirm the exact date of his entrance to prison: 8 January 1981, and contrary to what he claimed after his incarceration, he says he is writing a lot and this makes him happy. He is also working out in the gym, and not smoking much because he can’t get many cigarettes, but the food is good: “Tell your grandma to send me more paper” (letter from Fogwill to Andrés and Vera Fogwill, 23 January 1981). He advises his children not to go and visit him so often: he prefers them to enjoy the summer. He writes to Andrés, his eldest child: “You came on Saturday. You came on Sunday. Now go to the pool or to play football. Try to get your mom to allow you to go and sail” (letter from Fogwill to Andrés Fogwill, 25 January 1981).

Among the memories from his stay in prison, he recounts that one night while waiting to be transferred together with other prisoners, two brothers from Catamarca were reminiscing about their childhood and talking about what the soldiers ate in their outposts: the pichi, a small Patagonian mammal from the armadillo family that hibernates several months a year. One brother said to the other: “You can’t imagine what I’d give to eat a pichiciego right now.” Fogwill remembered this, and it was the origin of his 1982 novel Los Pichiciegos. He began to write this in April 1982, the day his mother was watching the news about the Falklands/Malvinas War on TV, and said to him: “Son, we’ve sunk a ship!” Legend has it—something the writer never denied—that the novel was written in three days without sleep, as though in a trance, and aided by several grams of cocaine. It was written in a small bedroom he lived in above his mother’s apartment. Los Pichiciegos tells the story of a group of Argentine soldiers during the conflict who survive and manage to avoid all the fighting by hiding out in an underground trench.

There are many documents in the archive that still need to be studied. For a short while, Fogwill began writing a diary. This was found among the drafts of his manuscripts, and is still being transcribed. Studying it could shed light, contextualise, and lend substance to the links between writers of that period, and the collaborative networks they created. Thanks to the archive, it is possible to reconstruct an image of Fogwill as writer, father, friend, and intellectual that would naturally lead to a biography.

Translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor and Faye Williams