For Fernando A. Blanco, who once asked me to write about this, with emotion.1

1

The Casa de las Américas2 published recently a new edition of Mundo Cruel, the celebrated short story collection by way of which its author, the Puerto Rican Luis Negrón, undertakes a tragicomic and candid review of homosexual identity in his country. That an institution such as this has opened its own closet to promote such a book may astonish those whose notion of it is anchored in its defense of certain political values from the 60s and 70s. The truth is that this volume is one of a small list of works that the Casa has added to its catalogue, creating a space for discussion about diverse and dissident sexualities in Latin America, which has allowed the Cuban reader to discover pages of Mario Bellatin and Pedro Lemebel, or to focus by way of texts like Abel Sierra Madero’s Del otro lado del espejo: la sexualidad en la construcción de la nación cubana, winner of the Casa de las Américas’ Historical-Social Essay Prize in 2006, on an opening for certain discussions that, although long-overdue, are beginning to gain a new intensity. Now, ten years after Sierra Madero’s book, the Artistic-Literary Essay Prize has gone to Diego Falconí, who amplifies the canon, in which Lemebel or Bellatin are already enshrined, to include other authors in De las cenizas al texto, Literaturas andinas de las disidencias sexuales en el siglo XX.

They are few, but they are there: gestures and actions that have been mobilized in Cuba during the last decade to offer gay, lesbian, transsexual, HIV/AIDS patients, and other members of the hypothetical national LGTBIQ community, ways of understanding themselves more exactly within that always unstable and controversial context that has been the Island since 1959. When Casa de las Américas decided to invite Pedro Lemebel to headline the Week of the Author in 2006, it was sponsoring a new return by the writer to La Habana, which he had previously visited as part of the Mares of the Apocalypse. The Pedro who returned no longer needed the theatrical effects from his time as a member of that tremendous duo. Dressed in black, and arrayed in androgynous attire, he sat at the back of the Manuel Galich auditorium and listened while scholars read pages and pages dedicated to his work as chronicler and narrator.3 He read, of course, his celebrated Manifesto at the opening of the Week, before the bewildered gaze of functionaries and personalities who perhaps, a decade earlier, would have flat-out refused to attend such an event. Pedro Lemebel’s art of mariconería,4 and queer verbality, would not only have been unacceptable, but also pernicious in political terms. Like a tropical Pasolini, Lemebel had returned to sign copies of his Cuban edition of My Tender Matador, and challenge us in a way that still remains unanswered.

I was one of those who read paragraphs about Pedro Lemebel in that Week of the Author. Recalling him now, in his penultimate visit to Havana, allows me to feel the weight of his commitment. He would come once more, an occasion that would end in mystery, after having disappeared in the middle of the Feria del Libro that was dedicated to Chile. This time dressed in white, he disappeared like a ghost, leaving his readers waiting, many of them young gay men who very likely had spent all their savings to buy his books in order to go home with a signature and perhaps a promise of love. He was not to be seen again. One would have to invoke him from his own writing, so that his presence among us is not reduced to a vague memory of his footsteps in a city whose nights must have suggested so much to him.

2

Cuban literature with a homoerotic theme awakened, as we know, at the close of the 1980s. Driven by the yearnings for change that the country was experiencing, the promise of a utopia that would collapse with the Berlin Wall, it gained ground along with other voices and characters in a social gallery that was being reorganized in formulas of promising diversity. In poetry, in playwriting, above all in the plastic arts, in the arrival to Cuba of dance theater and other variations of postmodernity, the level of doubt and call to individuality silenced for decades was now becoming perfectly audible, vexing the cultural hierarchs who feared, and were aware of everything that this, in terms of subversion, could awakened in readers and spectators. The foundational pieces, in the words of Victor Fowler in his volume La maldición, una historia del placer como conquista (Editorial Letras Cubanas, 1998) are a short story: “Por qué llora Leslie Caron?” [Why Does Leslie Caron Cry?], by Roberto Urías; and a poem, “Vestido de novia,”5 of my authorship. They are, rather than foundational, the link that connected a previous path, a sensibility that already existed in Cuban arts and letters, beyond the homophobic suspicion that would silence this project. Finally today, archeology and research allows us to consciously weave these texts of the 80s with the much earlier works of Emilio Ballagas, Virgilio Piñera, Julián del Casal, Carlos Montenegro, Ofelia Rodríguez Acosta, the journal Ciclón, directed by José Rodríguez Feo, and other signs that speak, with certainty, to the presence and discomfort of the homosexual and the lesbian in the memories of the Homeland, locating them there, especially, where political history has denied them with hidden anger through a charge of conscious forgottenness, of the virile rejection of the desires of unprintable bodies and risks. The tension that added as a taboo to the tradition of revolutionary legality, initiating the birth of the Military Units to Aid Production (UMAP, 1965-1968)6 or the parametrization (1971-1976)7 that during the so-called gray quinquennium8 not only erased homosexuals and other dissidents from their jobs, but also silenced new configurations of that desire that flowed as a defiant act through the works of certain members of the group El Puente (1960-1965); or of Reinaldo Arenas, the great survivor of Cuban letters. From these we learned that certain insolences were payable with silence or prison, fates also suffered by José Mario, René Ariza, Manuel Ballagas, Lina de Feria, and Dolphin Prats. Fear and political pressure plunged the Cuban homosexual into his closet, which he would abandon only under extreme pressure, such as the Mariel exodus during which, justly, to self-identify as gay was a sure bet for an immediate departure from Cuba. “We do not need them,” proclaimed the highest voice of political power at that time, in a celebrated speech. It was a question of manhood and courage, in which these subjects, these “seres extravagantes,” these “odd beings,”9 which Manuel Zayas homonymous documentary rescues, had no place.

It is difficult to put all these events into perspective, because in many of them the trauma, the pain, the resentment, the sense of a greater loss, still exist. The polarized view of the subject, as well as the lack of a thoroughness in the operations of exchange that have taken place throughout this development, continue to function as zones of silence. The journal Mariel, for example, whose editorial team included more than a few gay men and lesbians who arrived in the United States from that port that gave us the Freedom Flotilla, is one of those zones. The figure of Arenas, who has conquered post-mortem a dimension that was denied him in life, catapulted by the film based on his memoirs and directed by Julian Schnabel, to the displeasure of so many functionaries on the Island, serves as an axis to many of these remappings, due to the rabid nature of his extraordinary work and his presence as a political activist that makes difficult, even in the moments of opening that the Cuban government has recently orchestrated, his return to the Canon of cubanidad,10 in which other names that still live and hold radical positions continue to be uncomfortable. His statements in Conducta impropia, the documentary on the repression of homosexuals and dissidents, directed by Néstor Almendros and Orlando Jiménez Leal in 1984, continues to operate as the core of that suspicion, a film whose screening on the Island promises to continue to be delayed.

The arrival of the 90s pulled Cuba out of the closet not always in the most elegant way. Those first texts coincided with the confinement of patients diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in sanatoriums where, under military control, they were prevented from leading their public lives, in a strategy that would eventually come to an end, but which for years perpetuated the black legend that led many to believe that that the epidemic had reached the island in the diseased body of an artist, and not, as it did, through soldiers sent to Africa for the internationalist campaigns that the Revolution promoted. When the fragments of the Berlin Wall fell and chaos flooded Tiananmen Square, communism, as we had been taught from childhood, in schools and political acts, in terms of a rigorous doctrine, fell apart. The Nation was, as a body, devoid of resources to continue embellishing itself according to the patterns of that utopia. The young creators who burst onto the scene in Cuba in the 1980s were clamoring for a space of diversity and independence that collapsed into a space of disappointment and unease. Power outages, lack of food and electricity, disrupted that Cuba, in which one of the possible responses to the crisis was to incite in it, to take advantage of the fissures that the Political Program previously hid with its promises, to activate, in those spaces, new figurations so unusual as to fight for another kind of survival. Prostitutes, transvestites, gays, “fighters” of the day-to-day and especially of the night, erased from the national literature the previous heroes, reinventing Havana, above all, as a Babel, where the gestures and the costs that for a long time had been denied, emerged as keys to the challenge of the new hunting season.

It is this Havana that learns of the suicide of Reinaldo Arenas, who shoots himself and leaves a letter in which he accuses Fidel Castro of his death, as if Cuba’s leader had inoculated him with AIDS, together with the political hatred that sabotaged him. Reynaldo is our first deliberately queer figure, our national queen par excellence in times of Revolution, who learns from the patrician queens (Lezama, Piñera, Ballagas, etc.) the lettered cult of the Homeland, while mixing it with the tricks and trickery and of a creole pícaro, who escapes from deplorable prisons again and again, only to rewrite later, again and again, the manuscripts that his captors snatched from his hands. In Havana in the 1990s, however, reading him was still a forbidden act, and in a way continues to be, despite a few timid mentions. Virgilio Piñera, who had died in 1979 under another form of suicide: the silence imposed by the government and the cultural hierarchs who, even after the end of the gray quinquennium refused to rehabilitate him, is resurrected through the fervor of some of his disciples: Antón Arrufat, Abilio Estévez, Luis Marré, who rescue his works and begin to publish them. The theater revives Piñera not only through his great consecrated pieces, such as Aire frío and Electra Garrigó, but also through his so-called lesser pieces, in order to construct a bitter and cynical view of History, condemned to an eternal return, that ranges from the lesbian nuances that Carlos Diaz confers on the protagonist of La niñita querida in 1993, to the revision of Los siervos, his openly anticommunist fable, that Raúl Martin premieres in 1999, having altered numerous signs in the text to be able pass a censorship that has become more subtle. Piñera, too, returns from the tomb with a devastating poem, “La gran puta,” exhumed by Jesús Jambrina,11 in which we are shown from its most heartrending side: a queer manifesto where Havana is already, in that text from the early 60s, the very landscape and Pantagruelian theater that many narratives of the 90s (Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, Zoé Valdés, Leonardo Padura) will convert into a frequent image before their readers, above all foreigners. Piñera wrote with a bitterness that cost him dearly. His triumph, as an avowed homosexual who earned hatred for his mania of not silencing truths, is who we now cheer in a Cuba that resembles, in a terrible way, the nightmare he predicted. Had he known Virgilio’s poem, Lemebel may not have felt strange in that image of a marginal Havana (that of the 30s, which Viñera’s verses paint so crudely, and so similar to the later Havanas) where the author is already seen as poor, homosexual, and artist, three crosses with which he identifies in his unfinished autobiography, La vida tal cual, in fragments that would not be published until 1990.12 Poor, homosexual, and artist: these could also be a portrait-vérité of Pedro Lemebel, photographed in the Cuban capital where he would romp and, unbeknownst to him, walk in the steps of Piñera, who knew, of course, the famous anecdote featuring Ernesto Ché Guevara in the Cuban Embassy in Algeria, where the guerrilla threw a book by the playwright against the wall, who became enraged upon discovering on a shelf a title by “that queer,” as Juan Goytisolo would later relate.13

The revival of Piñera brought with it other conflicts: the homoerotic project of the journal Ciclón is debated, although never with the intensity worthy of the poetic zeal of Orígenes, where the figure of Lezama continues to hold court, inspiring, with the daring insolence of Paradiso, other followers, like Severo Sarduy. This famous novel would not be reprinted until 1991, twenty-five years after its debut; the launch of this new edition becomes a mythical reprimand, which prevented the book’s presenters from reading their encomia before the readers who mutinied to obtain a copy. But Lezama had in Cintio Vitier a sort of apostle who maneuvered with all his talent in an attempt to desexualize him, the poet, and much of the Orígenes group, and to turn it into a talisman whose brilliance foresaw the triumph of the Revolution; Piñera remains a corpse that continues to send us, from the hereafter, manuscripts, letters, equivocal signs that identify him as that subject who will never be silent, disposed to new discussions even from the grave. The only story in which Piñera chooses a homosexual character as the protagonist, “Fíchenlo, si pueden,”14 will not appear in a collection until his Cuentos completos are published, first by Alfaguara, in 1999, and then by Ediciones Ateneo in Cuba, in 2002, editions that also rescue “El muñeco,” his most openly anticommunist tale, which had been excluded from previous collections. That Arenas would name him in his furiously written memoirs as the figure of whom he beg sufficient time to complete his Opus before he was struck down by AIDS, increases the image of Virgilio as a force whose shockwave rocks Cuban letters at a level few could predict. Lezama and Piñera make up that channel that nourishes other writers, who, whether worshiping or discussing them, cannot escape the radical gesture that both, despite so many differences, established as a liberating act in our culture.

3

It is from here that codes are reorganized. The impact of “El bosque, el lobo, el hombre nuevo,” which won the Juan Rulfo Prize and will spread like a shockwave through various scenic versions (the first, La cathedral del helado, premiered in 1991 by the group Oscenibó; others would follow, including a version for musical theater, although the most felicitous is directed by Carlos Díaz with the Teatro El Público); later the celebrated film Strawberry and Chocolate, directed by Alea-Tabío in 1993, still remains a turning point within this trajectory. Published in the journal Unión (Lezama appeared on the cover), and shortly after by Ediciones Luminaria, this story lifted the silence surrounding the tense relationship between sexual and political dissent that for a long time the official apparatus of Cuban culture, and the State itself, had attempted to make invisible. The essential questions of Paz’s story, as I pointed out in the text I read during the Week of the Author dedicated to Lemebel, operated in a vacuum that for the reader and citizens of the Island meant that a seminal book sustained by these questions would not be published among us. That novel is, of course, Kiss of the Spider Woman, by Manuel Puig, whose only book published by the Casa de las Américas was The Betrayal of Rita Hayworth. Kiss…, a crucial text in this orbit, is better known in Cuba through its cinematographic versions and theatrical adaptation by the author himself, in which, as is known, a certain degree of subversiveness disappears, present within the textuality itself, which implies a political, psychological, and entirely revolutionary analysis, which is fused seditiously and gaily with the central fable: friendship and love, between a leftist revolutionary and the queen film narrator with whom he shared a cell during the Argentine dictatorship. In Strawberry and Chocolate, la Guarida, the lair, David’s refuge, replaces the cell, where the young communist comes to dialogue with the queer literato, and in a kind of penetration, undergoes an examination of conscience about culture and the strata of nationality that will change him forever. The Cuban film was also more discreet than its metatext, which is why Pedro Almodóvar, perhaps, called it “too sweet.” As part of a still unfinished discussion, the film took more than a decade to receive the authorization that allowed it to be played on national television, despite the success achieved in movie houses and its Oscar nomination, that award, which, after all, is nothing more than the image of a naked man beneath a thin veneer of gold.

In any case, what these cultural hierarchs wanted to avoid by preventing the film from being seen in every home on the Island, was already happening in another way. After the first texts mentioned here, books of poetry, stories, novels, in which the Cuban homosexual, the lesbian, the AIDS patient, etc., were unsilenceable presences began to be published and rewarded. Within that panorama there is, of course, everything. There are transvestites in El rey de La Habana, the most well-known postcard in the international literary market of a post-communist Havana. They appear, too, in “Fallen Angels,” a story by Joel Cano that received the Rulfo, before Ena Lucía Portela and Miguel Barnet earned it with those extraordinary pieces that is “El viejo, el asesino y yo” and “Fátima o el Parque de Fraternidad,”15 respectively. The stories of Miguel Ángel Fraga emerge from his experience as an inmate at the Los Cocos sanatorium and his nocturnal wanderings in a city full of pleasures and dangers. Pedro de Jesus López describes with an unerring hand that sphere in the stories of Cuentos frígidos, while Jorge Ángel Pérez, in his novel El paseante Cándido recurs to the picaresque to offer an image that is close to that of “La gran puta,” that poem by Piñera, who also takes the stage not only through his texts, but as a character, in works such as ¡Oh, Virgilio!, by William Fuentes; And Si vas a comer, espera por Virgilio, by the veteran Jose Milián. In Fumando espero, his second novel, Jorge Ángel Pérez dares to use the author of La carne de René as a protagonist, offering a delirious account of his stays in Argentina.

There is much more. And it is hardly surprising. The period of crisis stretched the old norms, while the pretext of the struggle, daily survival, allowed prostitutes and entrepreneurs of all stripes to appear as characters that justified any act in order to support their families. The famine of the 90s drove many artists and writers from the Island, including those baladistas who for years were like queens to the homosexual community who crowded into the Teatro Karl Marx to applaud them. In this absence, the transvestites who had previously imitated them in hiding, will occasionally be hired to fill the black holes in cabarets and some theaters. In Santa Clara, the cultural center El Mejunje, that space which is queer by nature, already had a tradition of welcoming the “strange”; following a tribute to Freddie Mercury, a weekly space was established, dedicated to female impersonation, in which some of the regulars were also patients from the local AIDS sanatorium. Numerous documentaries attested to this, and in doing so prolonged the first echo to channel these questions (No porque lo diga Fidel Castro, Graciela Sánchez, Escuela de Cine de San Antonio de los Baños, 1988). Visual artists, directors and playwrights, narrators, essayists, off and on the Island, joined these exchanges. But in 1995 the celebration of a Fiesta Nacional de Transformismo at the Teatro América was the last straw, and the agents of order and cultural officials responded with prohibitions and new measures to diminish this kind of outing. This kind of homophobic wave has come and gone, provoking at times anecdotes as spectacular as the unexpected parade of a group of activists from the United States and their Cuban friends waving a fragment of the Rainbow Flag in the Mayday parade of 1991 before stunned Party members who presided over the act, as well as the violent closure of the clandestine gay nightclub El Periquitón.16 His skin and mask hardened by struggles fought in the street, the gay Cuban has sometimes known when to retire in hopes of a more propitious light in which to reappear later, knowing that he is already part of a national gallery in which his space, despite everything, is already well staked out. Although the official press and the most controlled media provided little testimony of it. And although it knows little or next to nothing about the life and work of other sisters and brothers in the struggle, like Néstor Perlongher or Manuel Ramos Otero, who expressed in our language the avatars and demands of other dissident and desiring bodies.

4

I have had to review all this not only to imagine Pedro Lemebel, and better still, what he represents, on a stage as changing as it is populated by restrictive gestures. More than a few gays and lesbians arrive to Cuba believing, at present, that this history has been overcome, if they have even heard of some of these knots and traumas. When in 2008 the Centro Nacional de Educación Sexual, known as Cenesex, and under the direction of Mariela Castro, dared to celebrate in a public event the International Day against Homophobia, this organization of discreet work until that moment was not alone in having to alter its platform of responses and new projects. The event, which lasted all day with various events in Havana’s Pabellón Cuba and a gala of female impersonators in the Teatro Astral, stirred passions to a greater extent than expected. The date of the international celebration, May 17, was also the day that the official Cuban calendar dedicates to peasants, and more than a few people took the coincidence as an insult.17 The Cenesex, whose origins can be found in the Grupo Nacional de Trabajo para la Educación Sexual,18 founded in 1974, which has been operating under its current name since 1989, is an entity of the Ministry of Public Health and leading voice on his issue, even as, ironically, its own spokespeople have to remind us that those represented in the abbreviations LGTBIQ are no longer considered as patients of a pathology. Directed by a heterosexual, and directly linked to the Castro lineage that has ruled the country since 1959, the Cenesex has deployed an extensive campaign in which, in addition to advances such as sex reassignment surgeries that it offers to trans Cubans, elements of Pinkwashing that aim to give a less troublesome picture of the tensions between politics and sexuality that have existed during the last nearly 60 years in Cuba. Issues such as the UMAP, the treatment of gays and lesbians in processes such as the Mariel exodus, hate crimes and police harassment are often not mentioned in the presence the representatives of that other pink tourism that comes to the congas convened by the Cenesex, the creole version of the Pride marches,19 which, ironically, the Center’s director has described as superficial and carnivalesque, although she herself has accepted invitations to some in Europe. In a way, the actions of the Cenesex dusted off and reactivated a series of demands that the state apparatus refuses to accept with reforms being demanded to the Constitution that so many crave. The essential question lies in their willingness to bequeath that struggle to institutions led by gays and lesbians themselves, or the coexistence of their work, which can no longer be limited to a health project, with other walks of life that can be identified by new organizations which need not depend on the approval of the State. An issue of concern for more than Cuba’s gay population.

The leftist queen Lemebel could give us some signals to follow in all this. When he was most recognized in Havana, however, I was sure he would return. He did not ride naked on a horse, a squalid, Chilean Lady Godiva, nor did he shed his clothes in public acts to prove he was dressed as a woman. He read his chronicles in the Casa de las Américas (he declaimed them with a complicit delight that is unrepeatable), and after listening to the essays dedicated to his writing, he begged leave to retire to the cruising points that some Cuban friends had told him about, naming those sites without the slighted bit of modesty. His novel, My Tender Matador, was the act of defiance that, already ill, he was bequeathing to us. This folletín, as he insisted on calling it,20 is the provocative link between Manuel Puig’s novel, still unpublished in Cuba, and Senel Paz’s tory, stirring all their elements, characters and landscapes toward the greatest disquiet that the homosexual can feel or express when he decides to surrender, or better, to sacrifice himself, before the virile member of a Revolution that, perhaps as a male lover who desires to be cautious in the face of “what people will say,” accepts his offering and his presence only to a certain extent. If one searches his writings, references to Cuba leap out: that chronicle where he narrates the astonishment with which Silvio Rodríguez rejected one of his song’s being used as a battle hymn for the homosexual cause, his encounter with Omara Portuondo after a concert in Chile, the farewell To Ché, where he recalls the Guerrero’s homophobic gesture toward Piñera’s book, and above all, his encounter with the young AIDS patient who escaped from his confinement to meet him during the Sixth Havana Biennial which Pedro attended on behalf of the Mares of the Apocalypse.21 Those paragraphs announce, or prolong, what his folletín proposes: the memories of the Loca del Frente,22 who this time takes over the body of the young communist and possesses him knowing that the romance will have to yield to the political impulse of another battle.

The question that remains for me, now that Lemebel is no longer alive, is how to recover his trace, his footprints, his shadow, bequeathed as an act of queer defiance in Cuban letters. The novel was published here but was not reviewed as it deserved. Maybe its plot, in which the queenly protagonist gets what David, in Senel Paz’s story, did not dare to ask for, was too much for certain minds. The possibility of a Cuban edition of the Chilean’s chronicles seems remote, and this is to be regretted. It is in these where Pedro’s radical verbal operation becomes more obvious and challenging. And although the author confessed in an interview that if he couldn’t die in Chile, he would like to die on the Island, the discussion and assumption that he poses regarding Cuba and its policies still await new confrontations.

In a country where the gay man is accepted, with great difficulty, as a recognizable figure, the most challenging option of a queer attitude is still unthinkable. The political will to confront the established, the never-ending debate of issues, including those that have already been won that characterize the nature of the queer, the conscious dissidence that this implies, contrasts with the image of the gay, the lesbian or the transsexual person incorporated into the social programs that aspire to portray them as citizens who, beyond their sexual choices, we could tolerate without paying too much attention to that “detail,” “defect,” of “condition,” as it is still called. That uncritically assimilated figure has little or nothing to do with the nature of the queer, which, like so many activists, do not hesitate to publicly express their disagreements. But even one of those activists, Lemebel’s comrade in the struggle: the Chilean Victor Hugo Robles, also known as the Che of the Gays, had to tolerate a certain official disgust when he chose to march in the Conga for the Diversity of Cenesex with a banner displaying a photograph of the corpse of Ernesto Guevara. In Villa Rosa, a very recent documentary by Lázaro J. González, which attempts to introduce us to Caibarién, a coastal town, as a sort of paradise of tolerance towards gays, Adela, the only Cuban transsexual delegate to the Poder Popular, acknowledges that despite the advancements, she is only respected in the government for her relationship with the director of Cenesex: “for who she is and whose daughter she is.” In this terrain, even a hint of a queer attitude is still limited by the notion of acceptable social behavior that offers transsexuals and other people, as a way of insertion into public life, workshops so they can be employed as hairdressers, secretaries, etc. The intermediate terrain of disobedience, the idea of that performance towards the excess that the queer proposes, would probably be seen here as a danger to be quickly stopped.

What Pedro Lemebel proposes, not only with his writing but also with his presence, with the performance of his identity, is that we understand his figure as a subject that can no longer be erased: the homosexual who discusses the Revolution and the machinations of the Left from our participation in these emancipations, whether those who hold the reins of the process like it or not. If these phenomena have on so many occasions wanted to conceal the homosexual, to deny the possibility of their being in these cycles, Lemebel insists on manifesting a dissent that demands he be reckoned with, even from the margins where he himself chooses to be known. A gesture of reaffirmation that began for him when he chose his maternal surname to be use as an artist and activist, and with which he was consistent until the very end, paying homage to his friend Gladys Marín, and that, even if it shows the Loca del Frente incredulous at the possibility of an escape, toward the end of the novel. with her lover to the Cuba of the Revolution: “What could happen in Cuba that would offer me the hope of having your love?”23 also allows him to underscore his support for the political cause of the Island. In that chiaroscuro he found his voice as the fighter and agitator queen, a role that on the Island, however, would be difficult to assume because the essences of a porous and limiting sexuality continue to fight among themselves, against the narrow vision of duty to be a citizen who continues to rely on another kind of heroism, and who seems not to be aware of the nocturnal vibration that in this country unties other masks and cries out for other freedoms.

But there are stories from En La Habana no son tan elegantes, by Jorge Ángel Pérez, that let us imagine the presence of the queer in our narrative.24 Pérez is the author of “Locus Solus, o el retrato de Dorian Gay” [Locus Solus, or The Portrait of Dorian Gay], a story in which a queen imagines an erotic encounter with José Martí, a desecration that has cost its publication in Cuba. There is the queer attitude of Alberto Abreu, author and central voice of the blog Afromodernidades, along with the activist, editor, and researcher Yasmin Sierra Portales. Pedro de Jesus López prolongs his proximity to the queer, present in some of his stories, in the essay “Imagen y libertad vigiladas,” about Severo Sarduy, recipient of the Alejo Carpentier Prize for Essay in 2014. A playwright such as Rogelio Orizondo is, clearly, not classifiable within the interests or coordinates of the gay, if we accept what Kosofsky says in this regard in Tendencies. With works such as Perros que jamás ladraron, Vacas y Antigonón, un contingente épico, he exposes as few have in his generation a violence, a rabid gaze on his surroundings that is genuine in his queerness. The same could be said of the poet and playwright Legna Rodríguez, or of a show about male prostitution in Havana like BaqueStriBois, by the Osikán Plataforma Escénica Experimental. In all these examples, as in La Misión, the most recent pictorial series by Rocío García, there is a tense remapping between the body, the individual, the social space, and the political power that brings vibrations of a much more current and interesting Cuba than that which is seen in other areas of representation. Pedro Lemebel, I suspect, would have given his blessing to all those books and events as a hopeful sign in a country that has frequently rejected any application of queer theory in our context, branding it as sectarian gibberish that wants to be imposed from the American academy, as if this theory had not already filtered into the speech and though of so many Latinx activists and those of other latitudes to become, now, an instrument of affirmation and controversy that has become incessantly self-discussing. But its primordial texts are not known on the Island, where if there were such a hypothetical LGTBIQ community, it would be a conglomerate of people who for the most part would know little of their tradition, of the struggles and names that preceded them, and who has been educated in a sort of conscience ignorance that allows them to avoid, comfortably, the knowledge that could be used as a resource of self-identification.

5

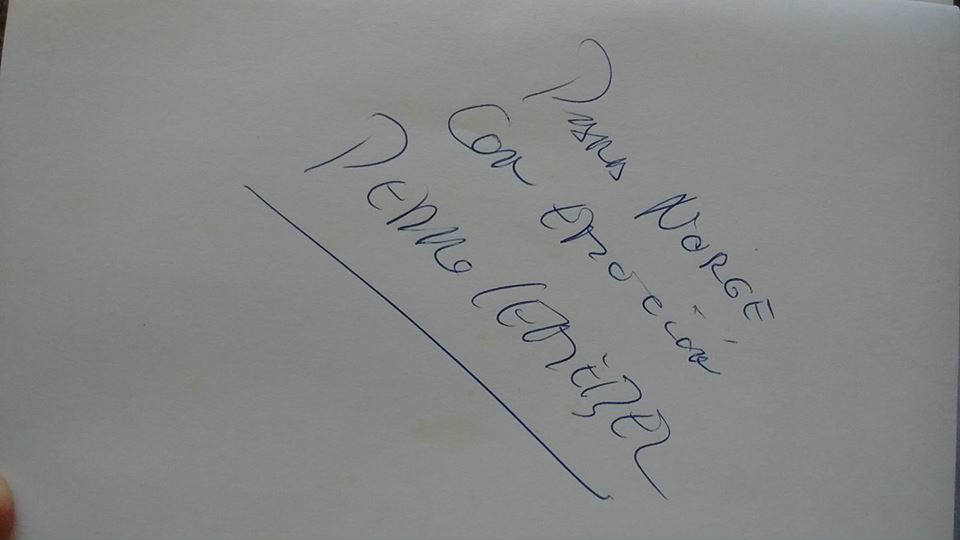

I conclude by imagining Pedro Lemebel’s last visit to Havana. Has he returned last December, he would have learned of the censorship that prevented Santa y Andrés, a film by the young Cuban director Carlos Lechuga, from screening at Cuba’s Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinomaericano. The film is inspired by the biography of some of those authors repressed and silenced in the 70s and 80s, for their irreverent texts and their lives as homosexuals, and imagines that between the protagonist and his monitor are able to create a mutual understanding that many still consider injurious to a certain idea of the Revolution. I imagine him, leprous spider, twisted orchid, soldier queen, trying to get his hands on a pirated copy of the film, or interrogating the officials who come to attend to him about such nonsense. It’s what he would have done, I tell myself, and what he compels us to do so that this mistrust dissolves like a bad spell that prevents us from contemplating honestly all our History. To tell our story from our difference, our discomfort: without it there will not be a true gay or queer community on the Island, because telling the story of our pain will help us to not repeat it. “For Norge, with emotion,” he simply wrote as a dedication in my copy of My Tender Matador. It’s with that queer emotion that I want him to return to Havana, to hear the tapping of his wounded, yet unrelenting, footsteps of a wounded warrioress on the cobblestones of the Plaza Vieja.

Translated by George Henson

Notes

- I have decided to leave many terms in this essay in Spanish and, where necessary, provide explications in footnotes. In the title, I have left herman@s in the original because there is simply no way to adequately render it in English. The use of the ampersand (@) as an inclusive gender marker, e.g. herman@ as opposed to hermano [brother] or hermana [sister], not unlike the use of “x” in “Latinx,” cannot be replicated in English. In effect, the use of both these symbols (x, @) is political in that they serve to degender a language that relies heavily on grammatical gender. The title could be translated as “brothers and sisters,” but the politicalness inherent in the use of the ampersand would be lost. – Trans.

-

Founded in 1959, just four months following the Cuban Revolution, the Casa de las Américas is Cuba’s most important cultural institution. In addition to promoting Latin American culture throughout the Americas and the world, it publishes a number of journals, as well as books. It also awards annual prizes in fiction, poetry, and essay, which are considered among the most prestigious in Latin America.

- During said Week of the Author Lemebel’s work was discussed in terms of a performer, chronicler, and narrator by Magaly Sánchez, Jorge Rufinelli, Fernando Blanco, Roberto Zurbano, Luis E. Carcamo-Huechante, Norge Espinosa, and Jorge Ángel Pérez, who was the editor in Cuba of My Tender Matador. The majority of these interventions appear in issue 246 of the journal Casa.

- Faggery. – Trans.

- The title of Espinosa’s groundbreaking poem presents an unresolvable challenge for the translator in that the title means both “bridal gown” and “a male dressed as a bride.” This ambiguity is, of course, intentional, but cannot be maintained in English translation. – Trans.

- These “units of production” were, in fact, agricultural labor camps where homosexuals, conscientious objectors and other “enemies” of the Revolution were forced to work. – Trans.

- Like the UMAP, parameterization was a euphemism adopted by the State to refer to a series of parameters that were used to define and limit acceptable conducts of behavior. Those who fell outside these parameters were labeled counterrevolutionary or subversive. – Trans.

- The quinquenio gris was a five-year period, from 1971-1976, of extreme censorship and repression. The term was first used by Ambrosio Fornet. It has also been referred to as the “Stalinist period,” which coincided with official efforts to Sovietize Cuban society and culture. – Trans.

- The title of Zayas’ film was “Seres extravagantes,” which is the term that Espinosa’s uses here. I have chosen, however, not to translate extravagantes as “extravagant” as it fails to capture the nuance of the term as it is used here. Rather than “extravagant,” the Spanish implies “strange” or “odd,” as communicated in the film’s English title, “Odd People Out.” – Trans.

- Espinosa is invoking here a term introduced by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz first in a speech delivered at the Unviersidad de La Habana in 1939 and expanded in 1961 in an essay published in the journal Islas. He writes: “What is ‘cubanidad’? The answer seems simple. ‘Cubanidad’ is the ‘quality of the Cuban,’ or rather his way of being, his character, his nature, his distinctive condition, his individuation within the universal.” – Trans.

-

“La Gran Puta,” in La Gaceta de Cuba, number 5, September 1999, as part of the dossier La galaxia Virgilio.

-

As part for the dossier Virgilio Tal Cual, in the journal Unión, issue 10, 1990

-

The anecdote is related by Goytisolo in his book En los reinos de taifa, pp. 174-175, Seix Barral, 1986.

-

The verb fichar is a police action, usually translated as “open a file” or “size up.” – Trans.

-

My translation of Barnet’s story, which I titled “Fátima, Queen of the Night,” can be read online here in World Literature Today. – Trans.

-

El Periquitón was a gay dance club housed in a mansion in Havana’s Marianao neighborhood, which is also home to the famed Tropicana nightclub. The disco, which was popular among foreign tourists, was raided in August of 199 by State security forces. It was later reported that on the night of the raid, Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar, Spanish trans actress Bibí Andersen, and French designer Jean Paul Gaultier were in attendance, although Almodóvar was said to have left prior to the raid. – Trans.

-

I cannot resist reproducing here, at least, the final stanzas of a few décimas [poetic compositions of ten lines] of the Cuban comedian Angel Rámiz, known in his theatrical and television appearances as El Cabo Pantera, which are collected in Decimerón, a compilation of popular décimas prepared by Yamil Díaz (Ediciones Sed de Belleza 2016), for the playful nuance they employ to define the reaction to which I allude: “Que esto no es chisme ni es brete/y me da genio, compay,/¡con tantos días que hay/escoger el 17!/Quiero que se me respete,/se me dé una explicación./Tengo una preocupación:/¿Ese día mis amistades/me dan las felicidades/por guajiro o maricón This is not gossip or a mess/but it pisses me off, my friend,/with so many days/why choose the 17!/I want to be respected,/to have an explanation./I have this concern:/When my friends on that day/wish me well/is it for guajiro or for maricón (country bumpkin or fag)?] (P. 129)

-

The Grupo Nacional de Trabajo para la Educación Sexual was an offshoot of the Federación de Mujeres Cubanas, whose director was, until her death in 2007, Vilma Espín Guillois, the wife of Raúl Castro and mother of Mariela Castro, the current director of the Cenesex. – Trans.

-

In addition to a style of Afro-Cuban music, the term conga refers to the musical groups that make up Cuban comparsas, groups of singers, dancers, and musicians that perform in Cuba’s carnavales. The Cenesex has appropriated this term to refer to the “parades” that take place during Cuba’s version of Gay Pride. – Trans.

-

The term folletín refers to the melodramatic, and often serialized, novels of the 19th century. – Trans.

-

The chronicle is “El fugado de La Habana” [The Havana escapee], which appears in Adiós, mariquita linda, Seix Barral, 2005. The chronicle of his failed meeting with Silvio Rodríguez also appears in Zanjón de la Aguada: “Silvio Rodríguez (o el malentendido del unicornio azul)” [Silvio Rodríguez (or the misunderstanding of the blue unicorn)], Seix Barral, 2003.

-

The Loca del Frente, or “Queen of the Corner,” in Katherine Silver’s translation, is the protagonist of Lemebel’s My Tender Matador. – Trans.

-

Katherine Silver’s translation. – Trans.

- En La Habana no son tan elegantes, Alejo Carpentier Short Story Prize, Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2009.