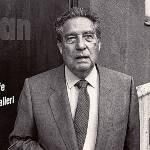

Editor’s Note: These remarks were delivered by Octavio Paz upon his receiving the 1982 Neustadt Prize. LALT presents them exclusively in English edition.

***

Dr. William S. Banowsky, President of the University of Oklahoma; Mrs. Doris Neustadt; Ladies and Gentlemen.

In all languages there are limpid words which are like air and the water of the spirit. To express such words is always marvelous and furthermore necessary, like breathing. One such word is gracias, thank you. Today I pronounce it with joy. Also with the awareness of being the object of a happy confusion. The truth is that I am not very certain of the value of my writings. On the other hand, I am certain of my literary passion: it was born with me and will die only when I die. This belief consoles me. The jurors were not completely mistaken in awarding me the Neustadt International Prize for 1982: they wanted to reward, in my case, if not excellence, then obstinacy. . . I shall not say more about my feelings. I am no more than the incidental (or accidental?) cause, and so what should count, however deep my gratitude, is not my person but the significance of the Neustadt Prize. It is worth reflecting upon this for a moment.

Situated in the center of the United States and surrounded by immense plains, Oklahoma seemed destined due to geographic fate for interior activity and historical apartness. However, the relation of every society with its surrounding physical reality is one of contradiction: men who inhabit a valley climb mountains which separate them from the world, and men of the plains move along the endless expanse as if it were a navigable sea. These are opposite and reversible metaphors: the desert is a sea for the Arab, and the sea is a desert for the sailor. In each case the metaphor is a challenge and an invitation: the horizon remains at the same time a call and an obstacle. In the domain of literary communication, Oklahoma has overcome isolation and distance through a series of exemplary initiatives.

The first was the founding of the journal Books Abroad in 1927 by Roy Temple House. I remember how many years ago, when I was studying for the bachelor’s degree and was beginning to discover literature for myself, a copy of the journal came into my hands. In those days the literary isolation of Mexico was almost absolute, to the degree that when I read those pages I felt the opening of the doors of contemporary literature in languages other than my own. For a while Books Abroad was my compass, and foreign literatures ceased to be for me an impenetrable forest. Books Abroad no longer exists, not because it has disappeared but because it has been transformed, enlarged and rejuvenated. Under the energetic and intelligent editorship of Ivar Ivask, a poet who himself is a lucid and intrepid literary explorer, the review has grown. It is now called World Literature Today and has become an indispensable periodical for all those who want to keep up with contemporary literature on a worldwide scale. I stress the word worldwide, which must be understood literally: World Literature Today is not dedicated only to the analysis of literature from the major European languages, but it also follows with genuine and admirable sympathy, not lacking in rigor, the development of letters in the so-called minor languages. It is no secret that these languages are often rich in notable works and original talents.

Following the example of World Literature Today and inspired by it, there have emerged during these last few years other activities which exhibit the same universal calling. One of these activities has been the series of symposia which are convened periodically at the University of Oklahoma honoring writers in Spanish or French. In these conferences critics from both the Americas and from Europe participate, and the papers and discussions represent, in many cases, essential contributions in the field of contemporary Hispanic and French literature.

Another manifestation, no doubt the most important to date, has been the establishment in 1969 of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. In many countries there exist national literary prizes to single out a writer in a common language of several nations. On the other hand, there are very few literary prizes indeed which are truly international. Among these a place apart is occupied by the Neustadt Prize. Two characteristics lend it a unique face: the first is that each jury is composed of critics and writers belonging to different languages and literatures, which means that it constitutes an international body, as international as the prize itself; the second characteristic is that the jury is not permanent but instead changes from one prize to the next—that is, every two years. These two characteristics translate into two words: Universality and Plurality. Due to the first word, the prize has been awarded to poets and novelists in Italian, English, French, Polish, Spanish and Czech; due to the second word, Plurality, we find among the laureates not only writers of different languages but also of different literary and philosophical persuasions. In esthetic terms, Plurality is a richness of voices, accents, manners, ideas and visions; in moral terms, Plurality signifies tolerance of diversity, renunciation of dogmatism and recognition of the unique and singular value of each work and every personality. Plurality is Universality, and Universality is the acknowledging of the admirable diversity of man and his works. Considering all this, in the convulsed and intolerant modern world we inhabit, the Neustadt Prize is an example of true civilization. I will say even more: to acknowledge the variety of visions and sensibilities is to preserve the richness of life and thus to ensure its continuity. Hence the Neustadt Prize, in stimulating the universality and diversity of literature, defends life itself.

Norman, Oklahoma

June 9, 1982