Bogotá: Seix Barral. 2022. 376 pages.

Ernesto Carriøn says he sits down to write with an idea of the story he wants to tell, setting off from an obsession he can’t shake off that follows him like a bloodhound. This is the inner guide that, once activated, abets every novelist in the act of imagining lives that are not—and, yet, are—their own (echoes, ghosts, projections). Lived things that leave behind a sediment in which creative dreams take root. Like a cat, this Ecuadorian writer has too many lives to settle on just one; he wants to live them all before he dies, one by one.

Ernesto Carriøn says he sits down to write with an idea of the story he wants to tell, setting off from an obsession he can’t shake off that follows him like a bloodhound. This is the inner guide that, once activated, abets every novelist in the act of imagining lives that are not—and, yet, are—their own (echoes, ghosts, projections). Lived things that leave behind a sediment in which creative dreams take root. Like a cat, this Ecuadorian writer has too many lives to settle on just one; he wants to live them all before he dies, one by one.

If we believe Borges (an article of faith for so many readers), Shakespeare was everything and nothing. We might think the same of Ernesto Carriøn as he unfurls a story in which he channels his inner guides to reinvent a setting in which a group of artists travels to Mexico to seek their fortune as creatives, just as the author himself did on a grant in 2009. This journey is stimulating and challenging all at once; it could be a springboard or a trapdoor for their ambitions, depending on the result of their efforts.

Ulises y los juguetes rotos moves forward in two directions. On the one hand are the grantees and their personal excesses, their intrigues, fights, and romantic entanglements; on the other are the stories they write to justify their upkeep. The novel’s structure is, therefore, ludic. Like a bargueño, one of those old colonial cabinets full of secret drawers and compartments, this novel by Carriøn entertains and interests us in many different ways. We might call it a bargueño of the psychedelic variety.

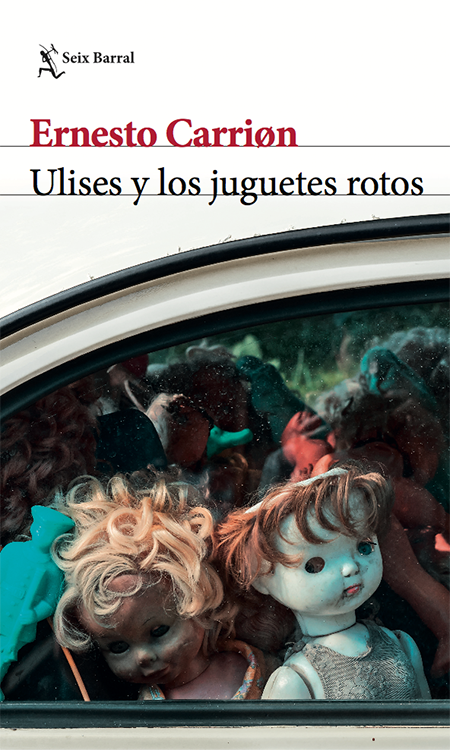

I met the author briefly at a book fair in the city of Quito, just a few months after his father’s tragic death. He held poems of mourning under his arm. I was impressed by his sobriety, his somewhat iconic presence, we might say—his air of a poet who leaves behind his old vocation to settle into the more rudimentary task of telling stories. Is it possible to cease to be a great poet in order to become a great novelist? I wondered. And the answer came to me some time later, when on the shelves of a bookstore I came across a book cover depicting a doll behind a car window, whose title read, beautifully, Ulises y los juguetes rotos.

Much has been written already about this novel in which a grantee of this name comes to Mexico along with a handful of other artists who long to find the work that will define them and give them a voice in the depressed panorama of Latin American letters: an unending search for oneself in which their tongues turn to ice, fire, or sacrificial smoke.

“ONE AFTER ANOTHER, EACH STORY SEDUCES AND AMAZES WITH ITS GENERIC AND STYLISTIC DIVERSITY, THREADING IN AND OUT OF THE EVERYDAY LIVES OF THE CHARACTERS”

Close beside the punctilious and insecure Ulises, Calibán (a typically irreverent and undisciplined young man from Guayaquil) lives an unhinged life of brimming sexuality with Lollipop, a sexually intense and loquacious Spanish woman with whom Calibán loses his way. With this relationship, the author parodies the incestuous bloodline of a Latin America emerging from the shadow of colonialism, surreally deformed in the story titled “Prácticas de caza del Antiguo Reino (cacería de indios en el futuro).”

As is necessary in this sort of environment, there is someone in charge of supplying the grantees with drugs. This is La Madre (the character to whom Carriøn feels most drawn, as he says in an interview): a Chilean who takes note of the incongruencies of our mixed-blood societies that put white women on their billboards, and that make impassioned pleas for ancestral cultures to be saved but can’t stand having an indigenous president. La Madre is a curious character: one who risks their life to get in touch with local drug dealers who threaten them if they get behind on payments, and who sets about writing a story titled “Diario de un narco o cómo sobrevivir como artista en un país lleno de culeros.”

I was blown away in particular by a story the author attributes to the grantee nicknamed Blancanieves (Snow White), whose main character is a bulimic girl healed by an intervention from Jodorowsky. To make this all the more delicious, the author elaborates the therapeutic procedure, which fits in beautifully with one of the famous healings outlined by the Chilean tarotist in his famed book Psicomagia. And what to say of the grantee nicknamed “La Escamada,” who spins a science fiction tale in which Gustavo Cerati lies comatose like a prince, only for her to stealthily pay him a visit and awake him with true love’s kiss? Not forgetting Hotel Elefante, the story I personally found most fascinating, which opens with a video of an elephant being electrocuted. Carriøn has said that, based on this story, he decided to develop the voice of the narrator: someone who goes to Coney Island and watches this film, which tortures him for months after. He cannot stop thinking about the elephant, and he has to write the story. An American dream. An electric chair, or, as the author tells it himself, “the need of the United States to electrocute its monsters.”

One after another, each story seduces and amazes with its generic and stylistic diversity, threading in and out of the everyday lives of the characters, who debate their Latin American condition as aspiring writers in a continent where artists must work more than one job in order to survive or make a living. They are rowing upstream, with neither agents nor income, applying for prizes and grants like the one this novel shows us, under the auspices of a State that does not back its writers and publishes books that (as in well-known cases in Ecuador) often merely slumber in boxes, forgotten in a futureless warehouse.

Carriøn throws everything on the grill: arguments, love affairs, conflicts between opposing personalities like those of Calibán and Ulises himself, a criminal attorney who longs fretfully to accomplish his purpose, to write the story that Carriøn puts off until the end of the novel: a story of Mexico built upon its native trees. This starting point refers back to myth: the trunk around which the flying men spin, the Totonacs whom Carriøn saw personally during his trip to Mexico alongside a real Ulises, a grantee of that same name whose death stirred the memory, in our Guayaquil author, of a few lost months.

Maybe that’s what writing is: diving off headfirst like a Totonac dancer, the author says. To read, to live, to mix the two together. Or, as Borges says: to fantasize with intention, giving shape to the vertiginous matter of dreams—something Carriøn does masterfully in this novel, whose series of stories gives him the chance to rein in the art of fiction with the bridle of the brilliant poet inside him.