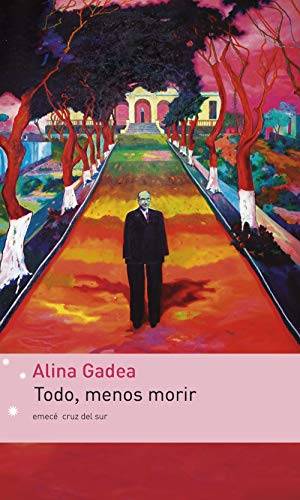

Todo, menos morir. Alina Gadea. Lima: Emecé, 2020. 100 pages.

Peruvian writer Alina Gadea’s first four novels include Otra vida para Doris Kaplan (2009), Obsesión (2012), La casa muerta (2014), and Destierro (2017). All four works follow the poetics of the nouvelle. They also share a preference for examining the inner worlds of the characters inhabiting their pages.

Peruvian writer Alina Gadea’s first four novels include Otra vida para Doris Kaplan (2009), Obsesión (2012), La casa muerta (2014), and Destierro (2017). All four works follow the poetics of the nouvelle. They also share a preference for examining the inner worlds of the characters inhabiting their pages.

Thematically, we can point to the profound coherence of Gadea’s narrative universe. Each of these works explores the characters’ private lives and, in one way or another, probes their darkest emotions and most traumatic, disturbing experiences. By delving into such emotional depths, these narratives avoid falling into the trap of purely confessional stories.

Gadea engages introspection frequently in her work through focalizations and an effective use of the narrative point of view. Motifs such as illness, disorder, breakdowns, loss, the line between sanity and madness, and the exaltation of emotions are concerns within Gadea’s fictional universe, as well as that of her contemporaries. Albeit from different angles, writers such as Margarita García Robayo, Ariana Harwicz and Jennifer Thorndike, to name a few, share Gadea’s interest in exploring the boundaries of illness and the limits of what is considered normal.

In Otra vida para Doris Kaplan, a key event is a father’s death, which plays out alongside another plotline: the Peruvian armed conflict of the 1980s and 1990s. This double narrative gives rise to an intense interchange in which the private and the public engage in a dramatic dialogue through the characters’ experiences.

Obsesión depicts a developing romantic relationship between a patient and her psychiatrist, although both parties experience this relationship in eminently different ways: for the psychiatrist, it represents a disruption to his existence and lifestyle, while the patient sees it as the beginning of a balanced relationship, one she has long desired.

In Destierro, the looming breakup of an intimate relationship (which we could call another kind of loss) is the central theme. Gadea offers fragmented sketches of the moments preceding emotional disaster, as well as all the emotions accompanying the mourning of intimacy that marks the characters’ lives.

La casa muerta narrates another version of an intense journey into one’s innermost self, a topic Gadea treats in each of her nouvelles. With a refined and concise language approximating poetry, Gadea outlines a space governed by memory and fantasy, eccentricity and surprise, obsession and melancholy, all within the closed, oppressive space of a house.

Todo, menos morir, Gadea’s most recent book, is no exception to the stylistic and thematic aspects of her narrative universe. On the contrary, it confirms her mastery of the genre and her sophisticated rendering of language that neither hides its pathos nor renounces the subtlety of poetry, which her prose often resembles.

Three narrative storylines converge in this novel. The first is of a couple in the midst of a crisis who go to the Larco Herrera Hospital in Lima for psychiatric help. In doing so, they resort to “the once magnificent shell of a building created to house those dispossessed of their own minds” [“ese resto de antiguo esplendor creado para albergar a los desheredados de sus mentes”] (11). The image of Peru’s most famous mental hospital is not superfluous, given it is where protagonist Sandro Tasso, Emilia’s spouse, creates a connection with Martín Adán, an eccentric and legendary Peruvian poet. Adán, as we recall, was admitted to Larco Herrera Hospital numerous times for alcoholism.

The second storyline, which certainly piques the reader’s interest even further, relates to the text’s metaliterary and self-referential dimension, which is confirmed in the narrative’s final lines. These last lines reveal that all along we have been reading Tasso’s manuscript about the poet, and this is where these characters’ trajectories overlap.

The third storyline ties directly to the composition and structure of Gadea’s nouvelle, which draws from the aesthetics of collage and the interpolation of multiple texts. Such texts include fragments of an essay Tasso writes about Adán, a story about Adán meeting beatnik poet Allen Ginsberg and their ascent up the stairs of the Europa Hotel a few yards from the Cordano Bar in Lima’s historical center: “I think I see the scene in which the poet and Ginsberg climb up to the Europa Hotel from the Cordano. A rundown staircase made of ancient marble weathered by time and the footsteps of poor customers taking them to the wooden door of a foul-smelling room. The door creaks and they go in. Poets” [“Creo ver la escena en que el poeta y Ginsberg suben del Cordano al hotel Europa. Una escalera rota de un vetusto mármol vencida por el paso del tiempo y las pisadas de pobres marchantes los lleva delante de la puerta de palo de una habitación maloliente. La puerta chirría y ellos pasan. Poetas”] (73). These lines recall two mythical locales in Lima’s bohemian history, and they may well represent one of the best moments in the story.

Tasso and Adán have much in common. They share a vocation for literature, each is plagued by alcoholism and a dark family history, and they both struggle with their homosexuality, as neither is able to express his sexual orientation openly and freely. Their relationship is not derivative or fortuitous; rather, it is a revelatory mechanism. Their lives are paralleled to a certain extent, threatened by insanity and solitude, by specters of the past and a somber present.

Naturally, the relationship depicted between these characters is a mix of fact and fiction, since Gadea incorporates references from Adán’s personal history into the story. These range from the obvious allusions to Adán’s biography, to his editor, Juan Mejía Baca, paying waiters at the Cordano bar for the poems Adán had written on napkins and left behind, or to his own family history. In addition to the above, Gadea includes allusions to critics such as Andrés Piñeiro, an outstanding scholar of Adán’s work. The fictitious elements are indeed those Tasso contributes to the narrative through his writing project.

Todo, menos morir is a nouvelle with an efficiently designed narrative and a captivating plot. With its poetic moments, punctuated at times with Adán’s verse, the narrative renews the interplay between fiction and reality, dreams and nightmares, writing and its secret mechanisms of artifice. Achieving all of this in a limited number of pages is certainly no small feat, and it is what makes Alina Gadea’s writing among the most interesting in contemporary Latin American literature.

Alonso Rabí Do Carmo

Universidad de Lima

Translated by Amy Olen

Proofread by Jenna Tang