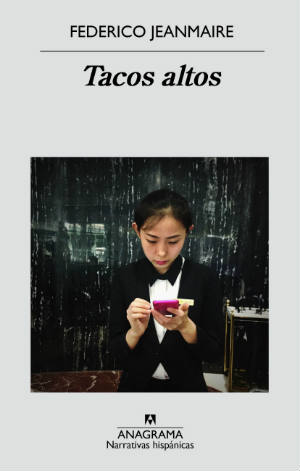

Tacos altos. Federico Jeanmaire. Barcelona: Anagrama, 2016. 166 pages.

What is essential and fun in the following phrase? “I find the past difficult. And I also find the future difficult. I’m Chinese, I always defend myself. But my Spanish teacher gets angry with me and then gives me a bad grade on my test. Am I Chinese? I dunno. It doesn’t matter now.” The phrase foregrounds the fresh voice, made of purely of present tense, ironic although practical, of a young girl obviously worried about her identity, but charged with urgency. If what defines a work, and more specifically those written in first person, is its voice, Federico Jeanmaire achieves in his new novel Tacos altos, as previously in Vida interior [Inner Life, Emecé Prize 2009], and Más liviano que el aire [Lighter Than Air, Clarín Prize 2009], a successful and distinct voice that establishes in the tone of an adolescent confession what in truth ends up being a profound and in some way universal, tragedy.

What is essential and fun in the following phrase? “I find the past difficult. And I also find the future difficult. I’m Chinese, I always defend myself. But my Spanish teacher gets angry with me and then gives me a bad grade on my test. Am I Chinese? I dunno. It doesn’t matter now.” The phrase foregrounds the fresh voice, made of purely of present tense, ironic although practical, of a young girl obviously worried about her identity, but charged with urgency. If what defines a work, and more specifically those written in first person, is its voice, Federico Jeanmaire achieves in his new novel Tacos altos, as previously in Vida interior [Inner Life, Emecé Prize 2009], and Más liviano que el aire [Lighter Than Air, Clarín Prize 2009], a successful and distinct voice that establishes in the tone of an adolescent confession what in truth ends up being a profound and in some way universal, tragedy.

The character that speaks, or better, that writes this journal (or diary) to which Jeanmaire gives us access, is Su Nuam, a Chinese teenager who lived in Argentina for ten years, where her father owned a small supermarket, and who travels to Buenos Aires for a few months before her return to China. If the identity of Don Quixote—about which Jeanmaire is an acknowledged specialist—is the result of his obsession with reading numerous works on chivalry, then the identity of Su Nuam is developed through her obsession with writing in her notebook/diary. “I have the hope when I arrive at the supermarket and open the notebook, that if I write in detail what has happened since yesterday, I can, in some line, maybe by chance, understand it.” The journal, written in the Spanish of her childhood, in the language that preserves the secrets of her life in Argentina, keeps the hidden parts of her past and her identity on center stage. It is written in an unusual present tense that corresponds, in some way, to the structure of the Chinese language, but that also corresponds to the most profound question of the timelessness of what one really is. In line with the Aristotelian legacy of what is actuality is already potentiality, the present tense is an excellent way to reflect on the central theme of the work, the passage from potential to act, which in some way is timeless and that reflects this Borgesian instant of knowing what one is capable of. In the same manner that Borges, in his “Biography of Isidoro Tadeo Cruz,” says, “Any life, however long and complicated it may be, actually consists of a single moment—the moment when a man knows forever more who he is,” the journal of Su Nuam says, “I guess that there’s a moment in life that every man and every woman discovers who they are. They know it, suddenly. Facing a crucial moment or facing an insignificant event, it doesn’t matter.”

The diary of Su Nuam brings us, always in the present tense, from the Sarmentinean spaces of the plaza in Glew where her father’s supermarket was in Argentina, to the much more vivid plaza in her village in China, from the presence of water in her place in China to her conversations in front of the river in Buenos Aires with her grandfather that made the journey with her to Argentina (as told in the story), from the insecurity of a young girl in the face of the criticisms of her Spanish teacher to her determination to claim that “Things happen, ma’am. And these things that happen, change us forever.” In the present tense, Su Nuam writes or lives, it doesn’t matter, this moment of her life in which she discovers who she is, and what she is capable of, this moment in which “I put on high heels to feel more grown-up, and I call the shots about what I should do,” that illuminating moment by which “the order of the world returns to normal. Justice triumphs over injustice. The smoke finally, eagerly, reaches the heavens. I’m not happy with the situation, I don’t enjoy it. But, at least I can communicate with the great beyond the same as any other Chinese woman. I am at peace. I am me.”

I frankly enjoyed the freshness that Frederico Jeanmaire infuses in the original voice of Su Nuam, the fatalism of the theme so Argentinian and universally understood, with the supposed practicality of the Chinese when she concludes her diary content that it’s finally complete, knowing who she is and also why, “and I still have five hundred dollars in my pocket to buy myself a lovely pair of pretty high heels when my plane lands in London in a few hours” (166). As in the rest of the recent work of Federico Jeanmaire, the construction of a unique voice is what is permanently in play and Tacos altos is an excellent entry point to the world of this excellent contemporary Argentinian author.

Carolina Sitya-Nin

University of Oklahoma

Translated by Emilee Romero