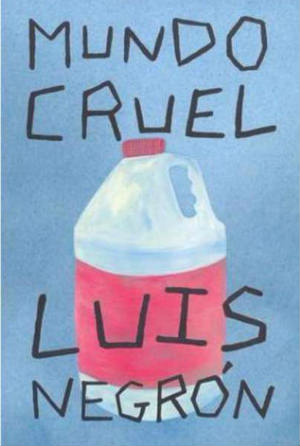

Mundo cruel. Luis Negrón. Río Piedras: La Secta de los Perros. 2010. 92 pages.

When one finishes reading Luis Negrón’s short story collection Mundo Cruel, one is convinced that with writers like him, this is a less cruel world indeed. The mastery of his language and the almost perfect conception of the characters, as well as the episodic nature of his stories, leaves us wanting more and much more. Sponsored by two Aces of Puerto Rican literature’s new promotions, José Liboy Erba and Rafael Acevedo, in addition to the accolades from Carmen Dolores Hernández’s post scriptum, Mundo Cruel reaches the Island’s literary universe as an instant classic, a black and white Polaroid that is developed before our eyes, and stays etched in our retina, where it will never be deleted. Whoever reads it will never forget it.

When one finishes reading Luis Negrón’s short story collection Mundo Cruel, one is convinced that with writers like him, this is a less cruel world indeed. The mastery of his language and the almost perfect conception of the characters, as well as the episodic nature of his stories, leaves us wanting more and much more. Sponsored by two Aces of Puerto Rican literature’s new promotions, José Liboy Erba and Rafael Acevedo, in addition to the accolades from Carmen Dolores Hernández’s post scriptum, Mundo Cruel reaches the Island’s literary universe as an instant classic, a black and white Polaroid that is developed before our eyes, and stays etched in our retina, where it will never be deleted. Whoever reads it will never forget it.

With epigraphs from Eduardo Alegría (“Faggotry is always subversive”) and Manuel Puig (“So then, a melodrama is a drama made by someone who doesn’t know the difference, Miss?” / “Not exactly, but in a certain way it is a second-rate product”), the nine short stories compiled in this collection smell like faggot desire, not queer not LGBT, nor any of those little words we have invented after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and her Epistemology of the closet. In Mundo cruel there are stories of aging fags getting it from pitchers (“The Vampire of Moca”), of protestant church pastors that sleep with boys (“The Chosen One”), of HIV/AIDS patients who die with dignity (“The Garden”), of gullible queens that end up in jail (“For Guayama”), of juicy gossips that go from ear to ear by cell (“La Edwin”) and of unsolved murders (“Botella”), among others.

All of them urban legends that are told in the setting of Santurce, Río Piedras, Guayama, and other villages in this Island of Fright, turned that way in our modern times due to the impact of a colonial economy and the dependency on the gringo metropolis. The conscience of people who haven’t been able to solve leaving room for faggotry is present in every story, like in “So Many, or On How the Wagging Tongue Can Sometimes Cast a Spell,” where two worried—extremely worried neighbors meet on opposite sides of the fence… and rip on everybody (63). This collective hysteria against fags is the center point of Mundo Cruel. The narrator appears irreverent and impertinent. He takes us by the hand to go out to the sordid outdoors of a city called San Juan, like René Marqués would do in his time or Luis Rafael Sánchez would in his. However, Luis Negrón is much closer to the narratives of Ana Lydia Vega (Falsas crónicas del Sur/False Southern Chronicles) or Magali García Ramis (Happy Days, Uncle Sergio) and Carmen Lugo Filippi (“Milagros, on Mercurio Street”). It also reminds us of that four-handed narrative experiment that Ana Lydia and Carmen Lugo published under the title Vírgenes y mártires, with which they shook the island’s panoply of literature in the 80’s. To me, Mundo Cruel resembles that and even recalls the dirty realism of Cuban Pedro Juan Gutiérrez (Dirty Havana Trilogy). We also get a glimpse of Mario Conde, from Leonardo Padura Fuentes’ novel Máscaras (Havana Red), about the murder of a transvestite in a Havana park. There are also bridges created between his generation’s colleagues, the HOMOERÓTICA Collective and the Sótano group. For example, the gay narrative of Moisés Agosto Rosario’s nightclub short stories, the raw sexuality of Max Charriez, my Conversaciones con Aurelia and Carlos Vázquez Cruz’s Dos centímetros de mar. Last but not least, is the accurate echo of Manuel Ramos Otero and his “Hollywood Memorabilia,” Concierto de metal para un recuerdo (Remembrance of a Metal Concert) short story, which seems to be the model for “The Garden.” This text breaks away somewhat with the tone of Mundo Cruel and opens the door to a narrative of a less cruel world.

Beyond the aforementioned possible literary echoes in the early work of Luis Negrón, we are left with the neatness of his words and the defiant gesture of street talk. A street that is hard and must be lived and revived every day in any corner, whether it is in Río Piedras or Santurce. Mundo Cruel is also a first installment about the city that opens and closes before its inhabitants. Leviathan that swallows and devours them to then spit them half chewed and leave them lying on the sidewalk, so that they can start over.

The last story, “Mundo Cruel,” which gives the collection its title, was originally published in the now classic anthology Los otros cuerpos: Antología de temática gay, lésbica y queer desde Puerto Rico y su diáspora (Tiempo Nuevo 2007), edited by Luis Negrón himself, together with David Caleb Acevedo and Moisés Agosto Rosario. “Mundo Cruel” presents us with the cruelty of two “fabulous and spectacular” queens, who don’t want to admit their faggotry to the world so that no one finds out the obvious, their homosexuality. The new equal opportunities policies at work make them disclose their “sexual orientation,” hence, the inner closet in which they have been living is revealed. One ends up “dancing a bachata right on Ponce de León with the man of his life” (91) and the other one selling everything and leaving for Miami (92). This story is key to understand the logic of the actions in all of Mundo Cruel short stories: it’s all about exposing the third city space of the gay and the butch lesbian (characters that appear sidelong in parties, like the silhouette characters in “The Vampire of Moca” short story). Luis Negrón does this deliberately and conscientiously, seeking the complicity of the male or female reader, without making any concessions to the general public who suddenly enters the LG world. Just like us, fags and dykes, who are born and cope with a purely heterosexual world. This is the contribution of this book to the counter-canon of a queer Puerto Rican literature that is more determined each day in its purpose. Luis Negrón’s Mundo Cruel thrives, prevails and raises despite those who still believe that writing is not an erotic act when it involves the encounter of two women or two men who seek, desire and love each other.

Daniel Torres

Ohio University

Translated by María Postigo

Ohio University