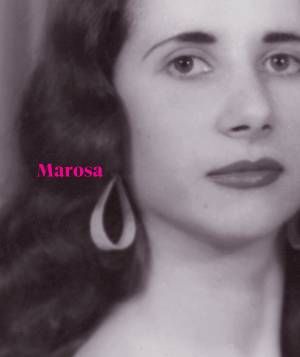

Marosa. Ana Inés Larre Borges and Alicia Torres. Montevideo: Cal y Canto, 2019. 203 pages.

The eternal little girl of hares and werewolves, who would become lost among orange blossoms and magnolias, the young woman who was a wedding columnist in her native Salto, the theater actress who abandoned her movie star dreams for her job as a city employee. The one with long hair who would walk arm in arm with her mother and sister along the main street, who would stare off into space while everyone else looked at the shop windows, the one with the cat-eye glasses, who wrote, won awards, and began publishing her poems while still a young girl. The woman who at 46 moved to the country’s capital, who in the afternoons would sit at cafés to read, who lived with her mother until her death; who fell terribly in love with Mario, the Puma, an impossible love, a fascination, the one who transformed everything into poetry. The countryside, the angels, acting, her dreams of becoming a diva, family, forbidden love, cafés, and eroticism. Marosa di Giorgio, born in 1932, poet, artist, eccentric and Uruguayan, worthy of reverence, today receives a new offering.

The eternal little girl of hares and werewolves, who would become lost among orange blossoms and magnolias, the young woman who was a wedding columnist in her native Salto, the theater actress who abandoned her movie star dreams for her job as a city employee. The one with long hair who would walk arm in arm with her mother and sister along the main street, who would stare off into space while everyone else looked at the shop windows, the one with the cat-eye glasses, who wrote, won awards, and began publishing her poems while still a young girl. The woman who at 46 moved to the country’s capital, who in the afternoons would sit at cafés to read, who lived with her mother until her death; who fell terribly in love with Mario, the Puma, an impossible love, a fascination, the one who transformed everything into poetry. The countryside, the angels, acting, her dreams of becoming a diva, family, forbidden love, cafés, and eroticism. Marosa di Giorgio, born in 1932, poet, artist, eccentric and Uruguayan, worthy of reverence, today receives a new offering.

A book can be a temple, a sanctuary to which one may retreat to meditate and connect for a moment with the mysticism of the sentences that were written with beauty and care and reside there. That is the case with Marosa, an album-book whose overall concept, coordination, and texts were compiled by researchers and literary critics Ana Inés Larre Borges and Alicia Torres. The idea originated with the symposium held at the National Library of Uruguay in 2005 in honor of di Giorgio, a year after her death, which was organized by Larre Borges—as she states in the introduction—and where friends and admirers created an altar with objects, drawings, and mementos; the rest is patience, seeing other similar works realize the dream of publishing an iconography, and interviews like in No develarás el misterio [You will not unveil the mystery], published in Argentina by El Cuenco de Plata in 2010, or the publication of particular texts in Otras vidas [Other lives] by Adriana Hidalgo in 2017. The wait and contrast with the materials shaped a creation stitched together with golden threads.

The chronological journey, the fragments of life, and its interstices are revealed in an album-book that does not differentiate life from work, and which shows—by preserving the mystery and dispelling the myth—the pieces of a puzzle hidden by the poet. Perhaps, as Roberto Echavarren states in the words he used—and which are included in the book—to bid farewell to his friend during her wake in Montevideo, returning to the work of one of the greatest poets of the Spanish language is the trap that di Giorgio consciously set. The imaginary must be reread to attempt to understand and to allow oneself to become engulfed by the magic. The archive, formatted as a chorus of refined selections of critical, intimate, and romantic texts as well as interviews, photographs, and poetry, with accompanying illustrations blended together by the rose and magenta-colored palette selected by the artist Pablo Uribe, is an excuse to pay tribute—like an obituary or a poetic will.

In light of the impossibility of dissociating life from artistic creation, and after reading the material in its entirety, certain behaviors of the poet can be detected in the conscious practice of her writing. The conception of a work and a career are reflected, starting from her early childhood, burning some books from when she was a little girl and asserting responsibility for what came after: Los papeles salvajes [The wild papers]. The homonymous book, published in 1971, was part of the poetry collection of the Arca publishing house and shared a cover design by Jorge Carrozzino—with a change in color—with Poesía 1947-1967 [Poetry 1947-1967] by Idea Vilariño, the year before, in green; a year later, Oidor andante [Errant judge] by Ida Vitale, in blue; Los papeles by Marosa was illustrated using an intense orange. In her letters written to Ángel Rama, Marosa seems confident and persistent with the editing of her published and unpublished poetic work, and in the letters that follow she requests to edit the proofs before sending them for printing. There is a detail that stands out: when mentioning her own bibliography, she removes her second work, Visiones [Visions], published in Caracas, Venezuela in the journal Lírica Hispánica in 1954, run by Conie Lobell and Jean Aristeguieta, with whom she published two additional works. Marosa does not claim authorship of Visiones.

Beyond brief perfectionisms, the telepathic and ominous look at a childhood spent on a farm offers—like a poetic path and a design of the gods, in its apparent other-worldly naivety—clarity and intelligence to move freely and establish a strong foundation in the power of her work. From early self-publication to becoming part of Arca, one of the key literary moments for the renewal of the canon in her country, Marosa was loyal to her private world, which was characterized as having its own voice in counterpoint to the representative conservatism that continues today in Uruguay. In combining some of the words of Alicia Migdal and Hugo Achugar, who appear back-to-back in the album, there may be extraliterary references that move beyond the evil lights, butterflies, and laborers, like the keenness for movie divas that she shared with her sister Nidia—the book includes an essential interview with her—during their adolescence, popular culture and syncretism, transformed into an idealization of a female diva, transvestite, and drag queen, which were a rarity and novelty in the village. Her red hair, long necklaces, gloss, and high heels were part of a lifestyle and belief about the world that Marosa endeavored to represent.

Wearing a constant mask of herself, but opening up to the greatest extent in her poetry, its voicing starting from her connection with acting in her youth, she achieved a sonority in her poems that, some say, magnetized the reader. Poetry, writing, performing, theater, and acting were natural in her daily life and interacted with the drama of her personal history. Added to what lies beneath are her personality and decision to write her own interviews, making them a part of her corpus.

The book invites us to read it as if it were a ritual, a sensory experience in a space to walk through like a flaneur adrift, and it pleads with us to trust and believe religiously, not in certain statements, but in poetry.

Leonor Courtoisie

Translated by Isabel González

Leonor Courtoisie dedicates herself to the practice and research of the performing arts, cinema, and literature. Someone once told her she could do things that don’t exist, and she tries to follow this advice. She coordinates Salvadora Editora and forms part of Sancocho Colectivo Editorial. She collaborates with Semanario Brecha. Her book Duermen a la hora de la siesta was awarded Uruguay’s Premio Nacional de Literatura in 2019. She also received the Molière Prize, awarded by the French embassy. She is a member of the Lincoln Center Directors Lab in New York. She recently published Corte de obsidiana (2017), written during an Iberescena residency in Mexico, and Todas esas cosas siguen vivas (2020). She writes, acts, revises, directs, and edits every day.

Isabel González-Gutiérrez is an MA student in Spanish translation at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. She has a BA in Political Science from San Francisco State University and four years of experience working as a community interpreter and translator.