Toluca: UAEMex. 2021. 84 pages.

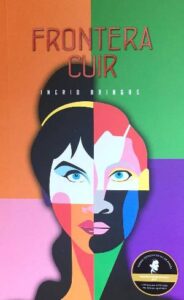

“En todo este silencio, ¿cómo se existe?” [In all this silence, how can one exist?] This question resonates on the page like an amplified loop that unpacks all its potential to live within us without expecting any kind of a response. And this is because in Frontera cuir [Queer border] (UAEMex, 2021), Ingrid Bringas (Monterrey, 1985) questions us voraciously, almost empirically, demanding we form an immoderate connection to what we are about to experience, starting from the moment we see the book’s cover.

“En todo este silencio, ¿cómo se existe?” [In all this silence, how can one exist?] This question resonates on the page like an amplified loop that unpacks all its potential to live within us without expecting any kind of a response. And this is because in Frontera cuir [Queer border] (UAEMex, 2021), Ingrid Bringas (Monterrey, 1985) questions us voraciously, almost empirically, demanding we form an immoderate connection to what we are about to experience, starting from the moment we see the book’s cover.

The word “queer,” rendered “cuir” in Spanish phonetics—which describes or groups together concepts related to people’s sexual identity or gender expression, and which was originally used as a pejorative term for gay people—acquires an emphatic drive within Frontera cuir, invigorated by empathy and self-awareness, circumscribed to the textual space and to the main threads that map out the entire book.

“But for a boy to look like a girl is degrading / Cause you think that being a girl is degrading,” proclaims the Queen of Pop’s post-2000 lyric, which simultaneously serves as epigraph to and sneak preview of “XY,” the poem which, in turn, begins the book. Ingrid starts to put forth a disquieting poetic structure, outside of the institutionally expected, which deconstructs the existence and persistence of stigmatized identities (especially those that pertain to LGBTQI+ culture: historically marginal, peripheral, and arbitrarily thrashed), also giving form to a new way of centering verses that denounce, that reveal, that expose, and that demand.

The displaced, the undocumented, the illiterate, the obscene, the floating bodies, those that die unidentified, the TV newscasts, the outskirts, the dirty dishes: inert main characters from a South America in pain, a socially and culturally lacerated piece of land that—still, for many—continues to verge on the “deforme e inequívocamente grotesco” [misshapenly, unequivocally grotesque].

The order of the day includes bullying, xenophobic speech, and all manner of verbal and physical acts of violence projecting their presence, opening up endless behavioral implications within and beyond the text.

Habrá quien se lave las manos / cuando dos mujeres bailan (…) / cuando dos mujeres bailan / tecno-cholitas / el mundo las mira / a través de sus calles sobrepobladas / left-right / left-right // el carnaval de Oruro en San Francisco / dos mujeres bailan y todo arde.

[There are those who would wash their hands / when two women dance (…) / when two women dance / techno-cholitas / the world watches them / from its overpopulated streets / left-right / left-right // the Oruro Carnival in San Francisco / two women dance and everything burns].

“Tengo derecho a ser este monstruo / que es parte de los telediarios / de los que mueren sin identificación / de las estadísticas / de los rostros cuir” [I have the right to be this monster / that is part of the TV newscasts / of those that die unidentified / of the statistics / of the queer faces], The challenge set by the author is centered in deep reflection on these questions, without diverting attention from what delicately pulls taut the book’s poetic architecture: its devices, its linguistic turns, its metonymic modes, its forceful patterns of repetition.

“Siempre es tarde para el cuerpo propio o el deseo de ser otro cuerpo o la sombra apenas del deseo” [It is always late for the body itself or the desire to be another body or the mere shadow of the desire]. The hypothesis of a binary gender system implicitly sustains the idea of a mimetic relationship between gender and sex, in which gender reflects sex or is limited by it. When the constructedness of gender is theorized as something completely independent of sex, gender itself comes to be an ambiguous artifice, with the consequence that the terms man, masculine, woman, and feminine can allude to a woman’s body as well as a man’s. In the words of Judith Butler:

If gender is the cultural meanings that the sexed body assumes, then a gender cannot be said to follow from a sex in any one way. Taken to its logical limit, the sex/gender distinction suggests a radical discontinuity between sexed bodies and culturally constructed genders. Assuming for the moment the stability of binary sex, it does not follow that the construction of “men” will accrue exclusively to the bodies of males or that “women” will interpret only female bodies. Further, even if the sexes appear to be unproblematically binary in their morphology and constitution (which will become a question), there is no reason to assume that genders ought also to remain as two.

Extrapolated to Ingrid’s poetry, any classification of individuals into fixed and universal categories would be fruitless, since gender and sexuality—as fundamental, basic human rights—have nothing to do with the biological attributes that have fallen to us by chance. And this scathing game that takes over the bodies of these poems relates directly to the abusive, oppressive reality that androcentrism, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia have placed on the shoulders of South America for decades.

The trans person, the lesbian, the “sudaca”: conditions of marginal dignity, textbook targets in an erroneously and falsely europeanized society, which looks to the different to justify its selfishness, its mounting greed, and its destitution. A reality, in sum, that plunges us into scenes we know all too well, and which finds its fullest expression in poems such as “Miss Cholita Trans:”

Miss Cholita Trans así le llaman / a veces buscando medicamentos caducos en las bolsas de basura (…) / Miss Cholita transita el cuerpo de un hombre / entre lo cutre de la tarde / sin papeles, Miss Cholita / donde lo último que le preguntan es el nombre

[Miss Trans Cholita they call her / sometimes looking for expired meds in trash bags (…) / Miss Trans Cholita traverses the body of a man / in the seediness of the afternoon / without papers, Miss Cholita / where the last thing they ask for is a name]

Or in “Qharimacho” [epithet applied to an indigenous person perceived as a transgressively masculine woman, a portmanteau of Quechua and Spanish]: “sin papeles / sin geografías / sin tablas / apenas la noche oscura / frente al tocador antiguo un cuerpo que no es tu cuerpo” [without papers / without geography / without qualifications / barely dark night / facing the antique dresser a body that is not your body].

The tension persists and insists. Perhaps, then, we should seriously consider the idea that “heterosexuality may not be a ‘preference’ at all but something that has had to be imposed, managed, organized, propagandized, and maintained by force,” which Adrienne Rich once forecast, or—to quote the author that concerns us here— that “para ser lo que se quiere ser es preciso abandonarlo todo / convocar la lucidez en pleno desastre” [in order to be what you want to be it is necessary to abandon everything / to summon lucidity in the middle of disaster].

Translated by Audrey Meshulam