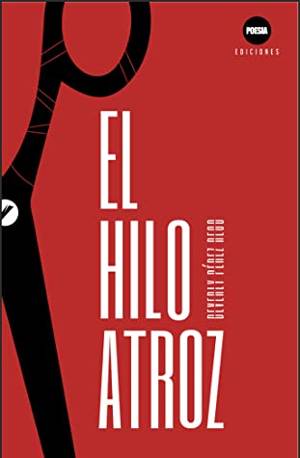

El hilo atroz. Beverly Pérez Rego. Valencia, Venezuela: Ediciones Poesía, 2021. 110 pages.

Spinning is ancient; it shelters bodies in amalgams of colors. Since this humble and silent craft was first practiced, many stories have been told in different cultures via fabrics. Whether coat or story, the threads stitch together the distinct movements of text as Barthesian notion. El hilo atroz (Ediciones Poesía, 2021), the most recent work by the Venezuelan poet Beverly Pérez Rego, occupies a space of reflection on coauthorial constructions in an appropriative sense, whose disfiguration of literary traditions, or of laying claim to them, succumb to being encrypted references, some more explicit than others.

Spinning is ancient; it shelters bodies in amalgams of colors. Since this humble and silent craft was first practiced, many stories have been told in different cultures via fabrics. Whether coat or story, the threads stitch together the distinct movements of text as Barthesian notion. El hilo atroz (Ediciones Poesía, 2021), the most recent work by the Venezuelan poet Beverly Pérez Rego, occupies a space of reflection on coauthorial constructions in an appropriative sense, whose disfiguration of literary traditions, or of laying claim to them, succumb to being encrypted references, some more explicit than others.

These references trace a modulation in tension, which is permeated by methods taken from poetry written by women in Spanish (especially methods produced in the Latin American vanguard) and in English (she draws on translations of Shakespeare, Virginia Woolf, certain forms of English-language modernism, and others), creating nooks where verbal products break parameters by using both languages; the peculiarity of the rupture comes to bring them together like loose threads. A verbal thread. A thread engendering Oneness, heterogeneous, an umbilical cord that constitutes paradigms to be expressed as unknowns in contemporary Venezuelan poetry, where this frame of reference, insofar as it is intertextual exploration, develops spaces of estrangement, a kind of split belonging, a mechanism of reclamation and renouncement of tradition: tribute and Luddism, homage and parody.

The text’s functionality rests on written materials that confirm a certain unfulfillment, an architecture of ruins, the streets of a space in chaos. Yet that chaos is present in the genealogy of a plural tradition, which travels toward a fractional language, converting the common thread of the book into a perennial foreignness: “¿Qué confuso laberinto es este, / donde no puede hallar / la razón el hilo?” [What confounded labyrinth is this, / where reason / cannot find the thread?”] A conjecture is made between what is illegible, what is vocal, and what is audible in the fabric as forgetfulness, since the fabric becomes bunched up and tattered. However, this comes to impede the handling of the machine itself and of the tailor’s workshop, that is to say, with its initial creation.

In the poem “Capítulo XIII (título illegible),” [Chapter XIII (title illegible)] Pérez Rego writes: “El taller es el templo, el taller es el tiempo” [The workshop is the temple, the workshop is time]. Thus, it is possible to demonstrate in that spinning a fleeting condition in which writing itself is the spinner, disfiguring the silence transformed into time, while this craft, in the past chiefly practiced by women, suffers damage; the act of spinning constitutes an exchange of the patriarchal for the matriarchal: “Las místicas arañas enhebran la herencia: hilvanan la matria, descosen la patria” [The mystical spiders thread the heritage: they stitch the motherland and unravel the fatherland]. And in fact that heritage begins to establish itself as a tradition that is often overshadowed by the masculinity of the canon, provoking, in turn, fluctuations and inadequacies, not only in this masculine space but in the feminine one also, especially when recalling poetry written by women in Venezuela: Ana Enriqueta Terán, Luz Machado, and Enriqueta Arvelo Larriva are named and referenced, but we also see a (mis)encounter with respect to these writers. It should be noted that, in this sense, Pérez Rego’s (mis)encounter with her precursors and the transposition of the book’s title is suggestive of the work El hilo de la voz. Antología crítica de escritoras venezolanas del siglo XX (2003), a compilation made by Yolanda Pantin and Ana Teresa Torres.

Nevertheless, as I mentioned, this molding of poets extends and goes beyond a Latin American space. There are clear caricatures and disfigurations of Pablo Neruda and César Vallejo, for example, while, in a different vein, as a form of Luddism and recognition, we see the names of Alejandra Pizarnik, Olga Orozco, Juana de Ibarbourou, and Lucila Godoy—the given name of Gabriela Mistral—among others. These names come to be, up to a point, interchangeable. Such an effect enhances the presence of hybrid names like Juana Orozco, which point to a space where the fabric becomes unnamable, constituting a function of mixing and assemblage, reflecting absolutely the poetics of Pérez Rego.

In this way, there appear phrases that suggest a collage of unoriginal genius (Marjorie Perloff), added to the assembly of parodic images, such as the figure of the hundred-bolívar note—allegory of the crisis and current hyperinflation in Venezuela—mixed with the epigraph of a translation of Ezra Pound by José Emilio Pacheco: “mella la aguja en manos de la hilandera / y embota su destreza” [blunteth the needle in the maid’s hand / and stoppeth the spinner’s cunning] from Canto XLV of The Cantos, whose version Pacheco titled “Por la usura.” As one can see, the references acquire a sociopolitical potential; their order/arrangement comes to model a patchwork quilt. They explore an unbridled barbarism that allegorizes the Venezuelan present. The sources, like in the poem “Informe,” end up playing a central role. These references manifest to the reader that writing does not safeguard an idea of originality, but just the opposite, since such sources interweave, to a large extent, a selection that interprets the concatenation the book proposes; there one can read names and titles as origins, which are self-referential so as to understand their recycling: “Ibarbourou, Juana: La promesa” [The promise]; “Lope de Vega, Que los libros sin dueño son tienda y no estudio” [Books with no owner are a store and not a studio]; “Quevedo, Francisco, Las tres musas últimas castellanas” [The last three Castilian muses]; “Mistral, Gabriela, Mientras baja la nieve” [While the snow comes down].

Referentiality and appropriation foment the thread itself; they are its ontological mark. Recovered female precursors, or mocked male precursors, whose texts are dissected and intervene and reiterate, contain a role that goes from translation as invention and poetics to the shifting of the Shakespearian monologue in its mechanics. To camouflage writing is to be other writings, to weave all those alien threads. The reader gets, despite the changing registers—poems in prose, long poems in verse and, occasionally, shorter poems—the manifestation of an elided, uncomfortable language of an in-between place. So mumbles the language of spinners—the blind ones, the dressmakers—who even cast aside the one who spins them as an indomitable materiality: “Resido en un reino de fragmentos que se inclinan, se doblan, platean mediatintas y astillas” [I reside in a kingdom of fragments that bend, fold, overlay mezzotint and splinters]. The spinners themselves are the genealogy of verbal fibers of a language that evaluates a Venezuelan condition in which exile also cuts tracks: “No distingo si esto es página o trapo. Mi condición de desmemoriada me impide honrar al plagiario de mi recuerdo […] Mi deplorable condición de venezolana me impide incurrir en el ditirambo, mas burlando la censura le digo al lector” [I can’t tell if this is a page or a rag. My condition of forgetfulness prevents me from honoring the plagiarist of my memory […] My deplorable Venezuelan condition prevents me from falling into dithyramb, yet cheating the censors I say to the reader]. So, that identity, known to be a peregrination, a forgetfulness, a forced silence, wants to be broken up into the rewriting of a tradition, soaked in distinct intertexts.

When the text is broken up into this thread, language is rarefied for having returned, for having left, for apparently not being anywhere. Nevertheless, this mutable stay has a name: Caracas, and that return is in some way imminent. The image of returning is a path in ruins, like the forgetfulness of spinning that Pérez Rego, in masterful fashion, proposes as so many textual artefacts to her readers.

Jesús Montoya

Universidad Federal de São Carlos, Brasil

Translated by Alex Halatsis