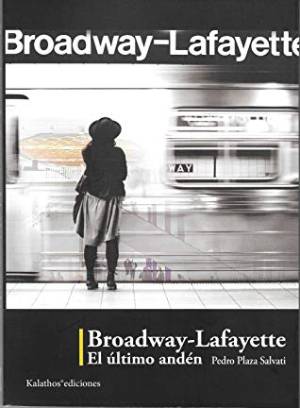

Broadway-Lafayette: el último andén. Pedro Plaza Salvati. Madrid: Kalathos. 2019. 350 pages.

Recent Venezuelan literature has been turning to an imaginary of the somber, buried, or abysmal with unsettling consistency. We find immersion in darkness as an elocutionary womb in both lyrical poetry—Blanca Strepponi’s Balada de la revelación [Ballad of revelation] (2004) or Igor Barreto’s Carreteras nocturnas [Nocturnal roads] (2010)—and in the novel—Ana Teresa Torres’ Nocturama (2006) or Rodrigo Blanco Calderón’s The Night (2016). In fiction, a true family of texts emerges in which the characters explore tunnels or investigate secret societies below the surface of cities. It’s important to name, in keeping with the inevitable works, Humberto Mata’s “Boquerón” [Anchovy] (1992), Gustavo Valle’s Bajo Tierra [Underground] (2009), or Carlos Sandoval’s El círculo de Lovecraft [Lovecraft circle] (2011). But we should not overlook the fact that the same motif reappears in other corners of the world: in a chapter from Víctor Carreño’s Cuaderno de Manhattan [Manhattan notebook] (2014), the Venezuelan protagonist becomes fascinated by the presence of the “mole people” in New York. Perhaps these repetitions could be explained as an allegorical treatment of the “underground” fate of the country since its existence began to depend, in many ways, on what lies in the subsoil—and the tradition would have one of its heights (or depths?) in José Ignacio Cabrujas’ Profundo [Deep] (1971), a theater piece that dates back to the so-called “Saudi Venezuela.” I believe, however, that the coincidences tend to be largely unpremeditated, less relatable to doctrines than to what Raymond Williams conceived of as “structures of feeling,” collective experiences still in the process of interpretation.

Recent Venezuelan literature has been turning to an imaginary of the somber, buried, or abysmal with unsettling consistency. We find immersion in darkness as an elocutionary womb in both lyrical poetry—Blanca Strepponi’s Balada de la revelación [Ballad of revelation] (2004) or Igor Barreto’s Carreteras nocturnas [Nocturnal roads] (2010)—and in the novel—Ana Teresa Torres’ Nocturama (2006) or Rodrigo Blanco Calderón’s The Night (2016). In fiction, a true family of texts emerges in which the characters explore tunnels or investigate secret societies below the surface of cities. It’s important to name, in keeping with the inevitable works, Humberto Mata’s “Boquerón” [Anchovy] (1992), Gustavo Valle’s Bajo Tierra [Underground] (2009), or Carlos Sandoval’s El círculo de Lovecraft [Lovecraft circle] (2011). But we should not overlook the fact that the same motif reappears in other corners of the world: in a chapter from Víctor Carreño’s Cuaderno de Manhattan [Manhattan notebook] (2014), the Venezuelan protagonist becomes fascinated by the presence of the “mole people” in New York. Perhaps these repetitions could be explained as an allegorical treatment of the “underground” fate of the country since its existence began to depend, in many ways, on what lies in the subsoil—and the tradition would have one of its heights (or depths?) in José Ignacio Cabrujas’ Profundo [Deep] (1971), a theater piece that dates back to the so-called “Saudi Venezuela.” I believe, however, that the coincidences tend to be largely unpremeditated, less relatable to doctrines than to what Raymond Williams conceived of as “structures of feeling,” collective experiences still in the process of interpretation.

This becomes clear in the case of Broadway-Lafayette: el último andén [Broadway-Lafayette: the final platform], the third novel by Pedro Plaza Salvati, where the journey to the underworld—the descensus ad inferos of antiquity—gets emphasized through its combination with another related mytheme: the loss of Eurydice. Any political reading that does not consider what these references suggest about the human psyche would fail to do justice to an impressive story due to the abundance of hermeneutic horizons it opens.

Early on, we come across an anecdote that is efficient for both sentimental reasons, on the one hand, and plot reasons, on the other, with parallel storylines of a marriage crisis and a planned extortion. But we will soon understand that this facade hides greater complexities. The couple of Andrés Carvajal and Cristina Mendoza will fall apart when he must return to a Venezuela besieged by material and moral crises, while in Manhattan she becomes obsessed with writing a novel about the subway and its beggars, analog to her own all-consuming subconscious on the way to frustration. Having left behind her native country, famous for its power outages and its crushing march towards destitution, the fact that Cristina abandons her husband to be absorbed into the great city of the First World by true human ruins and darkness presents itself to us as evidence of an impossible mental escape. The search for his wife undertaken by Andrés convinces us of the tragic fate of a relationship destroyed by the fierce pursuit of fictions. The final decision taken by this new Orpheus on a New York subway platform could even, as in the classical myth, tear him to pieces.

Plaza Salvati, however, is subtle and more intuitive than he is programmatic in his appeal to such references, whose appearances feel spontaneous. His writing always gives the impression of arising from a genuine plot-related interest in the development of characters with plausible psychology—with virtues, weaknesses, and contradictions. In Cristina, without looking very far, we confront vanities and emotional conceit—one of the latent threats in creative individuals if they remain trapped in the supreme instant of inspiration without a subsequent grounding in the trivialness of everyday life. In the picaros and villains that Andrés must contend with in Venezuela, we understand the effects of social deterioration on the values of a nation reduced to torturous subsistence. And, in a case like that of Andrés, it’s not difficult to perceive the erosion caused by vacillations between devotion to a marital past and the growing certainty of its dissolution, not so much due to circumstances beyond the control of those involved as to self-destructive impulses—to which Andrés himself could succumb if he does not learn to navigate solitude.

A reader eager to understand human nature will find sufficient stimuli in this novel. But I insist: one of the virtues of its author is knowing how to provide a wide variety of possible readings. And because the Venezuela of today is one of the elements put into play by the narration, the social approaches, in addition to the psychological and the mythical, become inevitable. For example, from the beginning, the country appears imbued with abjection following lustra of strident heroism with which its leaders have justified themselves:

Cerca del estadio había otro mercado en el que vendían pollo, carne y pescado, en la buena época de la abundancia. La escasez de alimentos no había llegado todavía al punto crítico y algo se conseguía. Cuando pasaba el camión de la basura se confundían los olores. Pero, por sobre todo, una vez que pasaba el camión, el olor a pescado castigaba como látigo en las narices, se hacía más notorio, como si acabaran de sacarlo del agua, de ese Mar Caribe, sección litoral venezolano: un mar enrarecido por las inmundicias que venían a joderles la vida a los peces. (37)

[Near the stadium there was another market where they sold chicken, meat, and fish, in the good times of abundance. The scarcity of food had yet to reach its critical point, and you could get your hands on something. When the garbage truck passed by, the smells blended together. But, above all, once the truck passed, the smell of fish punished noses like a whip, it became more evident, as though it had just been taken out of the water, out of that Carribean Sea, the section on the Venezuelan coast: a sea saturated by the garbage that came along to screw up the lives of the fish.]

Conducía de regreso al apartamento por la Caracas-La Guaira. El paisaje decadente no lo disgustaba como otras veces. Se había acostumbrado a subir y a bajar, ya no le causaban sorpresa los desniveles de la vía, el mal estado de la misma, los ranchos, el panorama antes de entrar al túnel de La Planicie, la cara de Chávez en todos lados. Ya no se sorprendía tanto con los perros muertos en la autopista ni con los motorizados. (184)

[He drove back to the apartment by way of the Caracas-La Guaira highway. The deteriorating scenery did not upset him as it had on other occasions. He had grown accustomed to going up and down, the unevenness of the road no longer surprised him, nor did its poor condition, the farms, the scene before entering into the La Planicie tunnel, Chávez’s face everywhere. He no longer felt as surprised by the dead dogs on the highway, nor by the motorcyclists.]

And, at the heart of the protagonist couple, an analogous abjection lies in wait due to the nonsensical delusions of grandeur that submerge Cristina into squalor:

—Mendigo o millonario […], que me dejaste por otro hombre.

—No fue por otro hombre. Era una necesidad literaria; lo tenía que hacer. Va a ser la novela más importante que jamás se haya escrito sobre la vida de los mendigos en el metro.

—¿Y dónde vives o vivías?

—En el metro. En un túnel del metro.

—¡Vivir peligrosamente! […]

—¿De qué hablas?

—De Osho.

—Ah, el autor de autoayuda.

—No lo menosprecies. Me permitió encontrar el sentido de vivir en Venezuela: vivir peligrosamente. Pero lo que tú hacías es mucho peor: vivir en la basura.

—Sí, tienes razón: por un tiempo ya parecía una mendiga. (332)

[—Beggar or millionaire […], you left me for another man.

—It wasn’t for another man. It was a literary necessity; I had to do it. It’s going to be the most important novel that has ever been written about the life of the beggars in the subway.

—And where do you live or did you live?

—In the subway. In the subway tunnel.

—Living dangerously! […]

—What are you talking about?

—About Osho.

—Ah, the self-help author.

—Don’t underestimate him. He allowed me to find the meaning of living in Venezuela: living dangerously. But what you were doing is much worse: living in garbage.

—Yes, you’re right: I’ve looked like a beggar for a while now.]

Plaza Salvati has continued to reveal himself as an attentive investigator of the urban experience at the dawn of the 21st century. This, his fifth volume, strengthens the contributions of his other works like Decepción de altura [High deception] (2013), stories rich in closeness to the hostile environment of Caracas, and most particularly El hombre azul [The blue man] (2016), a novel about the North American odyssey of a Venezuelan man alienated by his country’s deterioration and by psychological instability. In a savvy narrative wink, the first book appears in Broadway-Lafayette as Andrés’ reading material (84), while the protagonist of the second work appears as an incidental character (80-82). The great New York metropolis, no less, is put on display in Lo que me dijo Joan Didion [What Joan Didion told me] (2017), a collection of stories worthy of the Premio Transgenérico [Cross-genre prize] awarded by the Fundación para la Cultura Urbana de Caracas [Foundation for the urban culture of Caracas]. Plaza Salvati, from one work to the next, gives off the impression of having taken on one of the central experiences of Venezuelan culture in the last 100 years, that of the end of an agrarian economy and the subsequent growth of its cities, first with waves of modernizing optimism and then, suddenly, with the undercurrent of a failure that sinks both those who remain in the country and those who go into exile or emigrate into an abyss of sadness or hopelessness.

Miguel Gomes

University of Connecticut

Translated by Fiona Maloney-McCrystle

Miguel Gomes (1964) is the author of, among others, the works of fiction Visión memorable (Fundarte, 1987); De fantasmas y destierros (Eafit, 2003); Viviana y otras historias del cuerpo (Random House Mondadori, 2006); El hijo y la zorra (Random House Mondadori, 2010); Julieta en su castillo (Artesano, 2012); and Retrato de un caballero (Seix Barral, 2015). He has been the recipient of the Caracas Municipal Prize for Literature and has twice won the yearly short story prize awarded by the Venezuelan newspaper El Nacional. As a critic he has written extensively about the essay in Latin American and about various poets and fiction writers. Since 1989, he lives in the USA, and currently is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor at the University of Connecticut.

Fiona Maloney-McCrystle is a Translation and Interpretation student at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. She holds a bachelor’s degree in history from Middlebury College in Vermont.