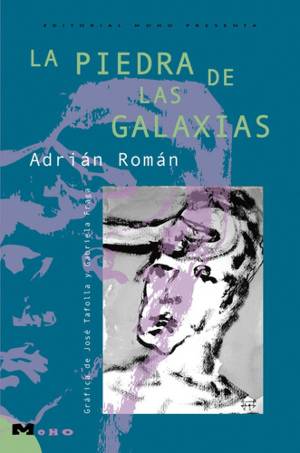

La piedra de las galaxias. Adrián Román. Mexico City: Moho, 2020. 156 pages.

The relationship between drugs and literature is as old as the Odyssey, spanning from the lotus-eaters and the wine with which Odysseus intoxicated Polyphemus to the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas de Quincey, who blamed Coleridge for introducing him to the relaxing droplets, to William Blake, whose doors of perception so powerfully influenced Aldous Huxley, and the Artificial Paradises of Charles Baudelaire, who this year turns 200. All the way to Jean Cocteau’s Opium and the Beat Generation. In short, the tradition into which Adrián Román enters is both broad and alluring. And, as if that weren’t enough, Román comes from the world of poetry; as an outstanding student of Eusebio Rubalcaba’s, he participated in the anthology Tres poetas perros. Interestingly, if one reads his verses carefully, there is already something of La piedra de las galaxias rearing its head: “Some days are a fistful of earth on your tongue, […] Some days are dry, rotten through,/ And they look at us out of the window,/ They wait for us down the stairs,/ They jump like a fish out of water. […] There are dogged days that don’t end,/ That don’t go.” Here as well, the narrator’s voice tries to reveal itself (and rebel) by means of writing, albeit in a depressed key: “My CV says nothing but my name. […] I knew decadence comes/ In a matter of seconds and never goes away/ It comes even for those who didn’t get a medal,/ For those, like me, who didn’t even run the race.”

The relationship between drugs and literature is as old as the Odyssey, spanning from the lotus-eaters and the wine with which Odysseus intoxicated Polyphemus to the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas de Quincey, who blamed Coleridge for introducing him to the relaxing droplets, to William Blake, whose doors of perception so powerfully influenced Aldous Huxley, and the Artificial Paradises of Charles Baudelaire, who this year turns 200. All the way to Jean Cocteau’s Opium and the Beat Generation. In short, the tradition into which Adrián Román enters is both broad and alluring. And, as if that weren’t enough, Román comes from the world of poetry; as an outstanding student of Eusebio Rubalcaba’s, he participated in the anthology Tres poetas perros. Interestingly, if one reads his verses carefully, there is already something of La piedra de las galaxias rearing its head: “Some days are a fistful of earth on your tongue, […] Some days are dry, rotten through,/ And they look at us out of the window,/ They wait for us down the stairs,/ They jump like a fish out of water. […] There are dogged days that don’t end,/ That don’t go.” Here as well, the narrator’s voice tries to reveal itself (and rebel) by means of writing, albeit in a depressed key: “My CV says nothing but my name. […] I knew decadence comes/ In a matter of seconds and never goes away/ It comes even for those who didn’t get a medal,/ For those, like me, who didn’t even run the race.”

And, in La piedra de las galaxias, he claims:

Not even the life of a loser like me is free of triumphs. It doesn’t matter if they’re second-hand. I remember the Chávez-Taylor fight.

I don’t even know what I would do with all the things I want to have.

I don’t even know for sure which is the true conflict of my existence.

I don’t even think you all know. You must have your own idea. The one that’s most comfortable and most resembles what you all are, the one closest to your own shortcomings. That’s how the portrait you paint of me will look. And the one I paint of you all. […]

I can’t even claim to be the most miserable. I have good luck, sometimes against my will. (p. 93-93)

This novel’s protagonist wanders the streets while confronting his fate, his inner world, and the space in which he might partake in just one more rock. He’s a man of letters whose character comes together through the pitfalls of an intense life of addiction. His monologues and descriptions represent deep introspections into his past and his reality. The people who surround him are brutally fantastic. Just as Baudelaire intended, Román has discovered the magic of the most self-sacrificial lowlives, the ones whose lives are truly thrown away and who always have something apt and lucid to say: “You were born protected by the moon, our holy mother, and by our holy Sun, the father who feeds us. You grew up with women. That’s why you’re corny, particular, and romantic. You like your old ladies posh and unfaithful. May they make you their own” (p. 32).

At the same time, he shows off a rather electrified style:

I focus on pulling off the wrapper. I can tell, just looking at the wrap, where every rock comes from. This one’s from the Death Star. I pick out a good-sized one. There’s still quite a lot of dust on the paper, but I prefer to hold on to it for a refill. I try to place it precisely on top of where I remember the holes in the can being punched. I flick the lighter. I let the flame start melting the cheese before I suck it down to the boiler.

I feel my soul has skipped between satellites with no fuel whatsoever before reaching me. It comes from somewhere far away, and before it fell to earth, on its travels, it came across a bunch of intergalactic garbage, bits of rockets, pieces of all imaginable metals. Cans, lighters, glass pipes burnt to shit, papers, empty bottles of Tonaya, León, and Cañita, shards of glass and plastic, empty cig boxes and micrometeorites. My soul bathes in lakes and rivers of methane and ethane. My soul is ten times bigger than Jupiter, or the planet Hd1069o6b. (p. 48)

Until I read La piedra de las galaxias, I did not realize the tremendous advantage of belonging to Mexico City’s lower-middle class: having to go out and work at the age of sixteen opened my eyes to the world. Now that we’re nostalgically remembering the nineties, and discovering that the world has not managed to show us grand new attractions, better dance spots, bigger nightclubs, glitzier atmospheres or tastier shenanigans, I see that this condition between knowledge and perennial desire that emerged from pop culture has given rise to a way of life in which the gaps in reality must be filled with a little imagination. A girl once told me, “You just love feeling up the books at Gandhi [the bookstore].” And maybe she was right: I prefer to long for a book than to get it. There are certain volumes—the biographies of Kafka, Stach, Johnson, or Boswell—I would die for, but when I got them home I stacked them up, not to open them again until this moment. And yet, how I longed for them, how often I went to see them, to find the best prices, to let the dealer at the shops or the Department know I was in the market. And that’s just it: what matters is desire, that erotic longing for objects. That’s why I think we might feel ourselves profoundly reflected in the main character of La piedra de las galaxias—not in his need for an “asteroid,” but in his dizzy rush to get hold of one, until the next rock, the next promise, comes along. Because what really matters is the possibility of failing or succeeding, always differently, always in some new fashion. This is why we sell all our property, get rid of all our comforts, or leave behind those who might offer us that exit—our bosses, our customers, or our editors. We see no reason beyond getting back to that longed-for rush of the sexual encounter, the next shot of adrenaline to convince us that the human form we’re dragging around is not already a cadaver.

Héctor Iván González

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon