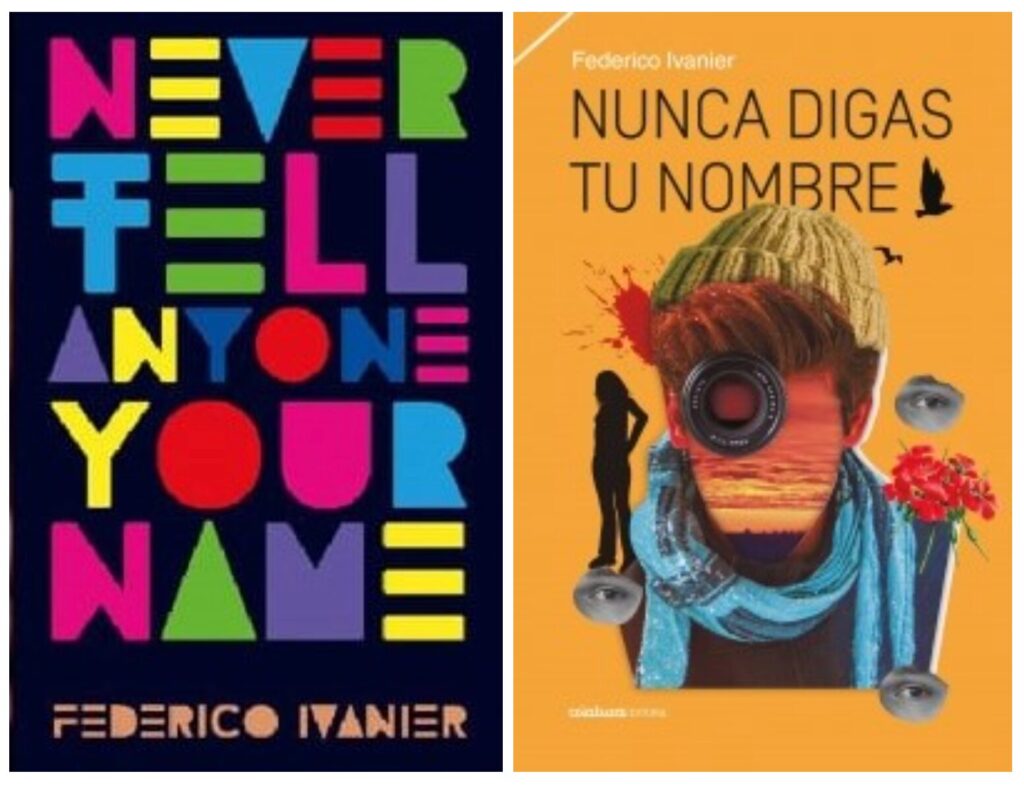

In this interview, conducted via email in May 2024, Uruguayan author Federico Ivanier and British translator Claire Storey discuss the essential value of books for young readers, the fraught definitions of “Young Adult Lit,” and their work on Never Tell Anyone Your Name, written in Spanish by Federico and translated into English by Claire, which was published by HopeRoad in 2023.

Arthur Malcolm Dixon: What inspired the two of you, as translator and writer respectively, to dedicate yourselves to books for young adults? What makes writing and translating for young people special and distinct from writing and translating for other audiences?

Federico Ivanier: I always found it curious that people wonder about writing for young people. It doesn’t happen the other way around: no one finds it curious that someone simply writes for adults. For me, writing for young people is natural. They seem to me to be incredible interlocutors. They are in transit, so to speak, and they have agile minds. A young reader connects very well with our need to tell things because that helps us to be who we are. That’s on the one hand. On the other hand, the life story of each author is reflected in their work. I am no exception. My adolescence—when I was twelve to sixteen years of age, to put a number on it—determined who I am, in many ways. It marked me as a reader, it made me understand the power of literature. For me, it’s inevitable, when I write, to connect with that.

Claire Storey: I came quite late to translation and during my MA in Translation Studies, we looked at a children’s picture book. I loved it! I realised then that this was a field I could actually work in. I became involved in World Kid Lit, an online platform highlighting the importance of translated books for young people, where I was co-editor for four years, and my interest really grew from there. Over time, my own translation practice has drifted towards the older end of the spectrum, where I can really get my teeth into a longer prose text.

Books for young people can be instrumental in understanding themselves and their surroundings, to see protagonists their own age in various different situations that they may identify with. In turn, translated books are so important for young people to learn about the world as they are growing up and developing opinions and identities, to see other cultures or traditions as well as seeing themselves reflected in those texts.

A.M.D.: Claire, what can you tell us about your “Young Adult Literature from Latin America” project, which received funding from Arts Council England? How did you go about presenting the project and why is it so necessary in today’s publishing world?

C.S.: The idea for the project came about in part through my involvement with World Kid Lit. We publish an annual list of titles for young people in translation, and it became clear that there were fewer books for older readers and barely any coming through from the Spanish-speaking Americas. In the UK, where I’m based, there had been no direct acquisitions for several years. I was also at a point in my career where I was ready to take the next step and hopefully gain more work. This then formed the basis of the project: to present books from the region to UK-based publishers in the hopes that someone would acquire the rights to publish the books and then hire me as the translator.

In choosing the books, I was influenced by an interview I did with Uruguayan writer and publisher Manuel Soriano for World Kid Lit, in which he expressed his frustrations around English-language publishers expecting a certain type of book from South America. I aimed to showcase a mix of genres and styles that challenged this idea—I wanted great books that happened to originate in Latin America.

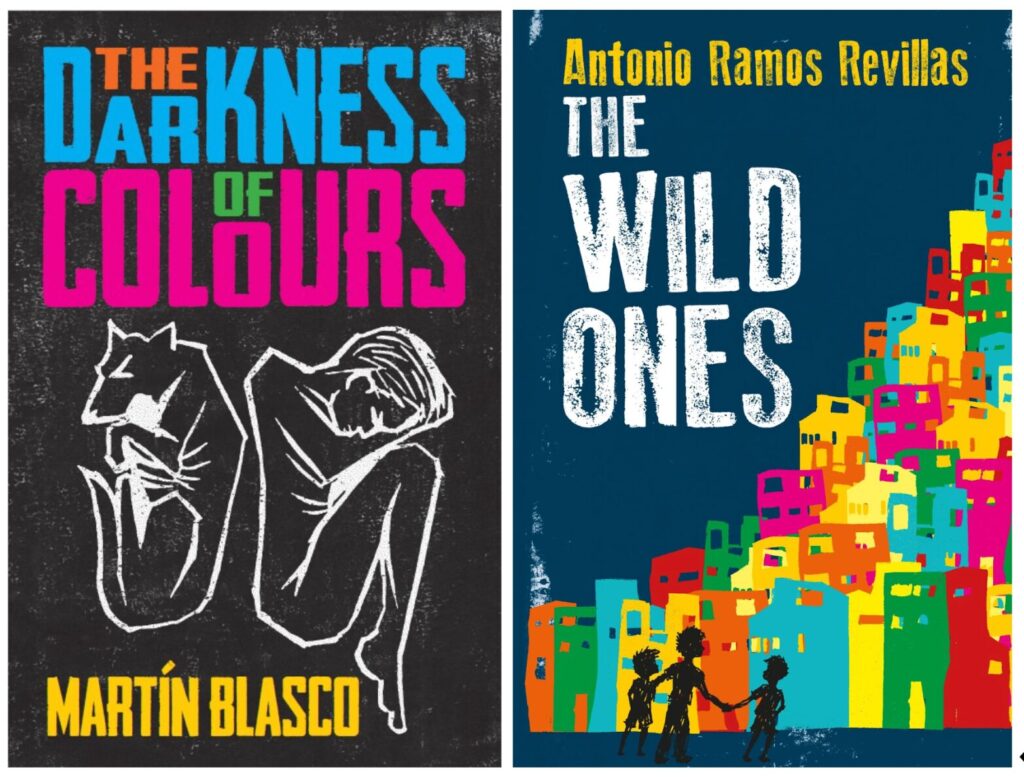

I created a document including details for each title together with translation samples and circulated it to UK publishers by email. The funding covered trips to the Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy and the London Book Fair in the UK, so I arranged to meet with some of the publishers who were interested. I was absolutely thrilled—and somewhat stunned—when Rosemarie Hudson at HopeRoad said she wanted to acquire not one but three of the titles. The second book from the project is The Darkness of Colours by Argentine writer Martín Blasco, and the third The Wild Ones by Mexican writer Antonio Ramos Revillas.

The joy of having a funded project was allowing myself freedom to choose titles that I knew might be more challenging for UK publishers because they’re beyond what might be expected. Dr. Emily Corbett, lecturer in children’s and young adult literature at Goldsmiths, University of London, reviewed Never Tell Anyone Your Name for #IntlYALitMonth and commented that “Ivanier’s novel… pushes the boundaries of the horror genre as we know it in the English-speaking world.” I’m thrilled by this recognition, as one of the aims of the project was to broaden the English-language publishing landscape.

A.M.D.: What do you think about the categorization of certain books as “Young Adult Literature”? From your perspectives, what characteristics set these books apart as a distinct type of literature? What, if any, are the limits of YA Literature?

F.I.: I feel that, when we talk about literature for any specific group, we’re not really thinking much about the text itself, but about the “ideal” reader—that is, a reader who, in theory, is the best for one specific text. This needs further discussion, but let’s just accept it as valid for argument’s sake. So, following that reasoning, thinking about “Young Adult Literature” isn’t so much about considering the characteristics of the books, or their limits, but about this supposed ideal reader. This is quite a topic because categorizations also respond to the market: a specific audience is constructed, and in this way, the consumers are too. In my opinion, outside of this “reader,” there isn’t much that makes literature for young people different. I understand that I have an ideal reader, but I am also writing for anybody who wants to read. It’s still literature. Nothing more. Nothing less.

C.S.: Following on from Federico’s point, it’s interesting that a recent article in the Guardian newspaper here in the UK suggested that “74% of YA readers were adults, and 28% were over the age of 28,” which begs the question, who is this imagined ideal reader?

I’m not always convinced that the labels we put on literature are all that helpful. In the English-speaking world, the idea of YA can be open to interpretation and means different things for different people, even within the same market. What is the difference, for example, between “Young Adult” and “Teen”? There’s also now an emerging category of “New Adult”. I see books for these age groups tackling big, complex topics, but one thing that perhaps sets YA apart from New Adult or adult literature is that it often includes fewer and less graphic scenes of sexual or violent content and less swearing.

When it comes to considering YA books in translation, this can be tricky because the categories we impose don’t neatly crossover. Some topics or language in one culture may be considered too old or too young, or taboo in another. Even the expected length of a book can be a consideration. I try to keep an open mind rather than being constrained by our own narrow ideas of what is or is not considered YA.

A.M.D.: How did the two of you come to work together? How did Claire become aware of Federico’s work and vice versa? What’s the story of how the English-language version of Never Tell Anyone Your Name came to be?

C.S.: Following my interview with Manuel Soriano, I asked him for recommendations of writers for older readers. He put me in touch with Julia Ortiz at Criatura Editora. We had a lovely Zoom call and she suggested I look at Federico’s books and put us in contact.

F.I.: I would say that all of this is Claire’s doing. She was the one who contacted me and started everything. All I have done is try to support her work.

A.M.D.: To what extent did the two of you collaborate on the translation of Never Tell Anyone Your Name? Did Federico intervene at all in the translation? Claire, do you prefer to work closely with the authors you’re translating, or to keep your distance while translating?

F.I.: My intervention was close to nothing. I fully trust Claire and her work. I also believe that a translation is a type of rewriting and that the translator should always have reasonable freedom.

C.S.: We were lucky enough to meet in person at the Young Adult Literature Convention in London in November 2023, where Federico was speaking on a panel. As we met, he had not yet read my translation!

F.I.: I wanted to wait to have the finished copy in my hands!

C.S.: I admit that was a bit nerve-racking. Federico is the first author I’ve really had direct contact with. He has been so supportive of the translation process, and given me the freedom to explore my process and create the English version of the text.

We are also currently collaborating on the translation of Federico’s first ever publication—The Sword of Fire (originally titled Martina Valiente in Spanish)—for Puffin Books, which is due out in April 2025. It has been quite a lengthy selection process and we have had to work closely to collate and prepare information to support our submission. I’m excited to see Martina come to life in English.

A.M.D.: What is the significance of Never Tell Anyone Your Name (and the other books Claire has translated through the “Young Adult Literature from Latin America” project) being specifically Latin American? Why is it important that Latin American literature—for young adults and other audiences—should be published in translation by UK presses?

C.S.: The aim of this project was to increase the representation of YA books from the region in the UK. Latin America is such a vast region and, from here, relatively far away, but it’s vitally important to hear different voices and stories, and as Spanish is so widely taught in schools over here in the UK, important also to recognise Spanish as a world language, not only European.

F.I.: Latin America has a unique but peculiar history; it’s a great blend of cultures and human journeys that we don’t find elsewhere. It would be odd not to consider that interesting. However, it shouldn’t be understood that the stories we tell in Latin America are more important than those told in other places around the planet. It’s just that the stories we tell in Latin America are unique to Latin America.

A.M.D.: What were the biggest challenges of writing and translating Never Tell Anyone Your Name? What were the funnest or most interesting parts of the work?

F.I.: For me, although it’s a short novel, it was a very long process. It took around fifteen years from when I began writing until the book was published. I wrote, rewrote, and abandoned the novel several times. I had two major breakthrough moments, the first one when I understood exactly who my central character was (when I understood his identity) and the second when I decided to use the second-person narrative. That mix allowed me to find the atmosphere and rhythm I was looking for in the text.

C.S.: This unusual second-person present-tense narrative was another reason why I chose this book—it was a challenge for me! It took me a while to find the narrator’s voice. I remember feeling frustrated at one point that the text didn’t seem to be flowing, so I set the text aside for a few weeks and concentrated on something else. When I came back to it, I was pleasantly surprised that the draft wasn’t as awful as I thought!

A.M.D.: Never Tell Anyone Your Name is, in part, a book about international travel and interacting with people who speak differently from oneself. How did you deal with the book’s geographical specificity and use of different accents in dialogue, both in the original and in the translation?

F.I.: When writing, I tried to use my own experience living in Spain for a year, but without resorting to slang. At least not too much. I believe slang distracts and tires the reader if taken to the extreme. Sometimes, it’s just the author showing off. The author is always present—this is quite obvious—but, I believe, in many cases, it’s not necessary to constantly remind the reader that you’re there. At times, even in entire texts and even if it sounds contradictory, the author should remain silent, and let the characters and actions take charge.

C.S.: The interplay between Uruguayan Spanish and European Spanish was really fun. The differences are so inherent in the Spanish verb conjugation, and as a Spanish speaker, you instantly recognise the geographical differences. This was much harder to ripple through the text in English where we don’t have those markers.

One approach I considered to this challenge was trying to play with UK and US English. I had an enjoyable conversation with my World Kid Lit colleague Jackie Friedman Mighdoll, who lives in the US, where we discussed our different speech patterns and turns of phrase. Ultimately, this approach didn’t really work, but it was great to have the space to discover that for myself. I decided in the end to add more pointers about the differences rather than including the differences themselves.

A.M.D.: The internet has had a massive influence on youth culture for decades. As a result, do you have the sense that international young adult readers have more in common now than they used to? Might we talk about a “global young adult culture” when it comes to books and reading? If so, what effects might this shared culture have on both writing and translating for young people?

F.I.: I don’t think the internet “creates” a new kind of teenager. In reality, with or without the internet, teenagers today face the same challenges as always: understanding who they are, what they desire, how to achieve it, how to coexist, how to transition into adulthood, what love consists of, or how to be yourself, and this is not an exhaustive list. None of this is answered by Instagram or TikTok. On the contrary, they bring more confusion. Besides, adolescence, like adulthood or childhood, is not the same for everyone. I don’t believe in generalizations. Sometimes, as adults, we need them because, deep down, we’re afraid of these young people who will inevitably take our place. Personally, I’m happy for them to take it, and I try to focus not on a person’s age but on other characteristics.

Also, with globalization emerge local responses. I wouldn’t like to think we are moving towards a global culture—that is to say, one that is uniform—because that would be like thinking that, in the sea, all fish are turning into the same fish. I want dolphins, sharks, whales, anchovies, the whole lot. Our cultural biodiversity is fundamental. And I believe it will always exist. Personally, as an author, I don’t want to write like anyone else or fit into a global concept.