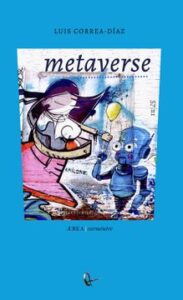

Santiago: RIL Editores, 2021. 110 pages.

metaverse is a love song to techno-scientific rapture, an electro-canto for the ages (space-, information-, digital-, and otherwise), a hexadecimal prayer with no return address, a message in a bottle made of dark matter and extruded plastic and integrated circuits. Suffice it to say that, before a book like metaverse that sets “poetry in metaverse / motion” (65), I find it difficult not to draw recourse to metaphor even in this opening characterization. In its formal and aesthetic hybridity, this veritable cyborg of a text resists straightforward description at every turn, demanding a certain playful dexterity of its reader, be they on Earth, Mars, or “en otro rinconcito / del multiverse” [“in another little corner / of the multiverse”] (93). A collection of poems that is, as the Spanish poet Vicente Luis Mora says in his introductory text, “the fruit of some (artificial) intelligence of the future in motion, metaverse works like an amphibian code that moves between two worlds, but also between two conceptions of poetry (the digital one and the one marked by tradition), between two languages and between two linguistic protocols, verbal and code, which demonstrate their (post)human compatibility” (7).

metaverse is a love song to techno-scientific rapture, an electro-canto for the ages (space-, information-, digital-, and otherwise), a hexadecimal prayer with no return address, a message in a bottle made of dark matter and extruded plastic and integrated circuits. Suffice it to say that, before a book like metaverse that sets “poetry in metaverse / motion” (65), I find it difficult not to draw recourse to metaphor even in this opening characterization. In its formal and aesthetic hybridity, this veritable cyborg of a text resists straightforward description at every turn, demanding a certain playful dexterity of its reader, be they on Earth, Mars, or “en otro rinconcito / del multiverse” [“in another little corner / of the multiverse”] (93). A collection of poems that is, as the Spanish poet Vicente Luis Mora says in his introductory text, “the fruit of some (artificial) intelligence of the future in motion, metaverse works like an amphibian code that moves between two worlds, but also between two conceptions of poetry (the digital one and the one marked by tradition), between two languages and between two linguistic protocols, verbal and code, which demonstrate their (post)human compatibility” (7).

To read metaverse is to participate gleefully—though not without trepidation—in the digital-poetic experiment Luis Correa-Díaz set in motion with clickable poem@s (RIL Editores, 2016), that truly lively bestiary of chimera-poems born of page and webpage, figurative language and code, all of which glow with the poet’s trademark grin and admiration for the granular and the cosmological alike. If a good deal of contemporary poetry attempts to offer a retreat into quiet contemplation—into a prelapsarian, seemingly pre-digital world—this collection of verse is resolutely of the current moment in its tacit expectation that we readers will have at the ready a camera-equipped smartphone, a prosthetic, hand-held eye capable of (machine-)reading the QR codes Correa-Díaz interleaves throughout this dynamic volume.

Through the interspersion of such “clickable textual devices allowing readers / to vicariously add prodigious screens / to the act of diving into the melancholy” (73), metaverse, true to its name, invites its audience to beta-test virtual reality using the poet’s own login credentials. As we read and click, click and read, we listen, “con un airpod en la oreja derecha, bueno / no, en la izquierda” [“with an airpod in the right ear, well / no, in the left”] (38), to the book’s curated soundtrack, watch video clips and whole documentaries as if alongside Correa-Díaz (or his avatar), and otherwise venture into a digitally mediated realm of hypertextual references in ways that actively challenge the perceived limits of the printed page.

By all accounts, metaverse occupies the in-between. Marked by a certain posthuman sensibility as well as a positively human sentimentality, at the core of Correa-Díaz’s metaverse lies “un fósil corazón siamés / que nunca se secó del todo” [“a fossilized siamese heart / that was never fully dried”] (50). Flirtatious in every sense of the word, the book is as eager to reach escape velocity as it is content to lull in Low-Earth orbit, nostalgic for places and people still there, long gone, or still to come, forever dreaming of this or that future (addressee) from the perspective of an uncertain here and now. In “cryonics,” the speaker muses that he “quisiera mandar este poema a alguna / agencia especializada en criogénesis” [“would like to send this poem to some / agency specialized in cryogenesis”] (68), expressing the same future-orientation and anxiety toward textual preservation that we encounter in “poema-concretion”: “cuando alguien in the far future / –en algunos millones de años– / llegara a encontrar este poema, / si lo encuentra, esto no valdría si no” [“when someone in the far future / –in some millions of years– / comes to find this poem / if they find it, this would not count if not”] (50).

Equal parts scientific and romantic, inquisitive and wistful, meditative and witty, metaverse is a doe-eyed, electrified Frankenstein that few would dare call monstrous. Better yet, metaverse is the Tin Man after his long-awaited heart transplant: homeward bound down the yellow brick road, the cyborg takes inventory of journeys past and conquests on the horizon, skipping along to R.E.M. and Carlos Vives and, of course, “Mr. Roboto.” To borrow a line from “crónica básica de un tatarabuelo,” metaverse “no es chiste, / plain sci-fi, ni menos imaginería poética, / nope” [“is not a joke, / plain sci-fi, much less poetic imagery, / nope”] (33) but something else entirely: digital poetry on the paper screen for a digital age, unique in its affordances and affect. PS: Headset sold separately.