Ricardo Forster has lived his life alongside ideas: as a professor and researcher at the University of Buenos Aires, as a public and private thinker—a witness to and actor in Argentine politics—and as a voracious, passionate reader of philosophy, history, and literature. His latest book, La biblioteca infinita: Leer y desleer a Borges (Emecé, 2024), is not just another book about Borges. It couldn’t be. It is, without a shadow of a doubt, a delight and a product of passion. For Forster, to read Borges is to read alongside Borges, around Borges, past and present; to become once again the same impassioned reader as ever, to return to the library where his own biography first began to take shape.

In this conversation for Latin American Literature Today (LALT), we returned to the longstanding curiosities that have moved Forster to write, to teach, to converse: journeys, childhood, books, reading, Jewish culture, Walter Benjamin, and much more. It is no exaggeration to claim that, in these times of twilight, books—our ever-loyal friends—are not only the last refuge of the true reader, but also a way to recall the value of friendship amid the madness of our twenty-first century.

Marcelo Rioseco: Welcome, Ricardo. We’re here to talk about your latest book, La biblioteca infinita: Leer y desleer a Borges, which was published in 2024 by Emecé press in Argentina. I’d like to start with a question that might seem simple, but I suspect there will be many facets to your answer: Why Borges? Or, in other words, why Borges now?

Ricardo Forster: You know, I asked myself the same question. This book is the product of an old text I had lying around since the nineties. At one time, I was very interested in Borges, I read him constantly, and I started writing about him, but the text got left behind, forgotten. Some time ago, perhaps as a result of the pandemic, or perhaps due to a change in age or timeline, I felt the need to return to it. I wanted to capture my experience as a reader of Borges, but, at the same time, open myself up to the worlds he presents. Coming to terms with Borges is, after a fashion, a debt I think every Argentine involved in the world of literature, writing, teaching, the humanities, philosophy, the essay, or poetry ends up settling. Sooner or later, you come up against his impact, his influence, his magnitude.

M.R.: So we might say, in a way, this is a personal book. I mean in the sense that we readers assign to a book that works with an author’s intellectual biography.

R.F.: That’s right, on the one hand, and on the other, it was also an opportunity to put together many pieces of my own intellectual jigsaw puzzle. As I was writing, I was doing free association, which led me, for example, from Borges discussing the Quran to Richard Burton, and from there to Emilio Salgari. Or, if I was discussing a theological subject, I might get lost in gnosticism and take a trip into Jewish mysticism. There was a certain anarchy, but also a certain order in putting all these pieces together. This evokes the idea of the library’s infiniteness. It’s like when Borges says how, for him, reading an encyclopedia was always an experience linked to chance, to the unforeseen. And, in a sense, Borges forces you to read this way, mixing erudition with ironic play, nostalgia, childhood, journeys, the way we see the world, hallucinations, obsessions.

M.R.: This also seems to be a text in which your library engages in dialogue with that of an author whose own library, at least in certain regards, is quite similar. Was there a particular Borges you wanted to show here, one you thought had not yet been seen?

R.F.: In recent times, I’ve felt a growing revulsion toward a form of ignorance that is eminently present in contemporary society—not just in Argentina, but the world over. It’s a sort of plague, an inclination toward the binary, toward reducing knowledge to mere opinions, toward revelling in ignorance as if it were an ongoing pleasure to inhabit a world where raised voices, rejecting the other, and the death of thorough argumentation are seen as virtues. And I was interested in bringing Borges into this context, especially in a country like my own, where everyone recognizes his genius, but he is still a controversial figure, especially from a political point of view. What Borges represents within the Argentine dichotomy of Peronism and Anti-Peronism, his own rejection of Peronism, turns him into an author who still generates debates today. Borges is a thinker who forces you to contend with multiplicity, diversity, and contradiction. He allows you to see how literature can exist in a space where prejudices, dichotomies, and dogmas fade away, and where an author with a different political ideology can nonetheless feel touched by his work.

M.R.: As I was reading, I was reminded of a provocative question that Ricardo Piglia once asked about Borges on Argentine public television: “What are we to do with a right-wing writer?” I think it’s a great question, and you address it very explicitly.

R.F.: Piglia asks an excellent question. A significant part of twentieth-century literature was written by right-wing writers: Pound, a fellow traveler of fascism; Eliot, a conservative very much adjacent to reactionary conservatism; Borges, a liberal conservative with flights of anarchism; Céline, a Nazi collaborator and genocidal antisemite. And, nevertheless, these four authors are inescapable when we think of the literature of the twentieth century.

If we think a work of literary art is to be measured by the political opinions or ideologies of its author, we are treading shaky ground. This does not mean there is no connection between writers’ values, political ideology, and modes of political participation and their body of work. There is always a connection, but, at the same time, there is something that must be extracted.

M.R.: And what is it that produces that difference, that can be extracted from literature?

R.F.: I think the genuine literary work is what can be extracted from good political intentions. When I say “good political intentions,” I mean from either the right or the left. When the author lets himself get carried along on the flow of the language itself, of the formal structure, of the subject that leads him toward a given work, that architecture may be influencecd by his political ideas. But, generally speaking, what lasts is, in fact, his creative power, which is not a product of his political ideology. The effort to transfer an idealized vision of the world into literature has generally failed, resulting instead in an unbearable sort of literature because, among other things, literature is the product of what goes wrong, what is unresolved.

After so much talk of engagement, of the relationship between the author, politics, ideology, and creativity during the twentieth century, reading Borges is also a way to question a dogmatic vision of the connection between politics and literature. Of course, Borges had that translated into horrible opinions. Is there, for example, an aristocratism in Borges? The answer is no; as an author, he is also fascinated by the barbaric, the uncivilized, and certain aspects of popular culture.

M.R.: What you’re saying runs counter to what’s happening with cancel culture. In this day and age, it’s almost impossible to separate the art from the artist. This brings to mind what’s going on with the concept of “great literature,” which is called into question so much today. There’s a line from your book that struck me as very interesting: “When my intelligence declines, I’ll no longer concern myself with great literature.”

R.F.: (Laughs.) That line is an ironic play on words from a reflection made by my fellow Forster—the English writer E.M. Forster, author of A Passage to India—when he’s describing his reading of Carlyle and, above all, of Emilio Salgari’s “Swiss family Robinsons.” He says, “When my intelligence declines, I shall have to focus not on the things that once concerned and interested us, but on what truly matters: great literature.”

Great literature is that unique experience, between childhood and adolescence, when reading a book is literally an extraordinary journey that stays with you forever. There comes a time when one must leave behind the obligations of political correctness, the obligation to respond to the “coherence” between what is written and the actions of the one who wrote it.

M.R.: Which is the opposite of what’s now happening all over the place, especially at universities.

R.F.: Of course. For example, Borges could be canceled for many things that he didn’t write but that he said, because there are many different Borgeses. There’s a Borges from the sixties on, the Borges with the cane, the icon who talked his mouth off and gave a million interviews. The paradox is that, with the exception of those horrendous, woeful statements—like when he met with Pinochet and Videla, or those that are absolutely denigratory—Borges was not a person who could be classified as particularly racist. But, nonetheless, in the Borges of his spoken words, there is a proliferation of ideas, of creative power, which is also present in his body of work. The question is: What do we have left if cancel culture takes over?

M.R.: Not much. These things are always paradoxical: Neruda was cancelled for his personal life, but not for his ode to Stalin. But that line about great literature reminded me of Borges’s opinion when he claimed he wanted to be contemporary, but then he discovered that, in reality, we are all inevitably modern. That idea is linked to shedding certain obligations in order to read great literature, which is not anchored to time, to the demands of keeping up to date.

R.F.: I’ll give you an interesting example. Borges, for much of his life, defined himself as a man of the nineteenth century. He played with the idea of having been born in 1899; he said, “I am a man of the nineteenth century living in the twentieth century.” In his youth, when he was more involved with the avant-garde, he even lied about his birthdate and claimed to have been born in 1900, presenting himself as part of the future, of the century of grand transformations. For my part, having been born in the middle of the twentieth century, I feel like a foreigner living in the twenty-first century, but one who writes under the impact, the influence, and the legacy of the past century. Borges, again, opens space for dissonance in the face of what is or is not allowed under current academic norms, under the demands of contemporary theories and inquisitorial discourse on the cancellation of writers.

M.R.: Is there an example from Borges’s work?

R.F.: There’s a fantastic Borges story called “The Theologians.” In it, he plays with a confrontation between two theologians: at first, one is orthodox and the other is a heretic, but over time, the heretic becomes the orthodox one and condemns to death the one who was once in his place. But, when the orthodox one dies and goes to meet God, he discovers that, in God’s eyes, he is indistinguishable from his adversary; in essence, they are the same. This is an interesting idea with which to question the closed-minded, dogmatic, and deadening nature of certain contemporary ways of reading. The twentieth century was a terrible, complex century: it was born as a wager on the future, but it ended up surpassing all conceivable horrors. At the same time, it was unusual in that it blended everything together, leading to a fullness in the artistic, literary, and philosophical sphere that now seems to be a thing of the past. In Borgesian terms, I feel I am still in that past, because that is precisely where I can bring the present into discussion and inhabit it in a different way.

M.R.: That leads me to a subject that is presented head-on in the book: childhood. You start the eleventh section with this idea: “The lived continuity of childhood throughout Borges’s life protected him from excessive formality, sheltering him from that exigency that is proper to the adult world.” And there’s something more to this than simple nostalgia for childhood as a lost space, a locus amoenus. How does this theme function in Borges’s work?

R.F.: Very few writers really return to what they read as children. In that regard, Borges has no prejudices. When he says, “I never left the library of my parents’ home; I saw the world through the books I read,” he is merging childhood with reading. How so? Reading as a child is the only time when a reader is fully a part of what he reads. Reading as an adult, on the other hand, is mediated; it is a form of reading marked by distances and involvements that establish a difference between what is written and the act of reading. Borges dwells permanently in life as if it were a continuous experience of endless reading. To give an example: he traveled a great deal after he went blind. What he “saw” was what he had read: he saw the cities he found in books or the tales they recounted. Thus, the journey transported him back to his own childhood—to the exact moment when reading became real and reality turned into literature. It is as if Borges the child—who read the One Thousand and One Nights, Stevenson, Carlyle, and Mark Twain—were always rebuilding a continuum with Borges the writer, Borges the oracle, the Borges who would later face the world.

M.R.: It could be said that all the different Borgeses within him converge into a single Borges, which is Borges the reader.

R.F.: It seems to me the Borgesian experience is an experience constructed within the pages one reads. Borges also often appears as overly naïve or excessively distanced from the noise of the world. He made sure of this himself, saying, “I would have liked to be a soldier in the wars for independence of the nineteenth century,” and writing a masterful story, “The South,” in which the protagonist—almost his stand-in—goes in search of his mythical origin and dies heroically in the presence of Borges, who sees himself as a weakling, entirely lacking in adventure in his life. But this was not exactly the case: Borges had a life before his blindness; he was a great walker of the city—not the illuminated city, but the city of shadows, the city on the margins. Borges would have liked to inhabit the peripheries, the margins.

M.R.: Of course. He saw in the heroic associations of the arrabal, the fight with the compadrito, a heroism he always longed for; that’s why the story “The South” could be read as a poetics of his own life.

R.F.: For Borges, the adventure is always literary. And there is a certain circularity in his conception of time, which is clearly expressed in one of his stories, “The Circular Ruins,” in which the story of a sorcerer dreaming of his son gives way to the revelation that he too is the product of another’s dream. In turn, in Borges’s writing we find the idea of the edge, of the margins, the idea of the periphery, but there is also the center. He can be read as an author who is absolutely saturated with the literature of the Río de la Plata, and also, at the same time, as a cosmopolitan author, a polyglot, fascinated by the babelic structure of language.

M.R.: Another subject that is very much your own, inasmuch as you have written a greal deal about it, is that of a writer who also appears here: Benjamin, of course. This intersection—which is not unpredictable, knowing you, but is very much so when it comes to Borges—is very well depicted in the book, because you touch extensively on the subject of Jewish culture; what you call, if I remember correctly, Jewish filiations. And then Benjamin appears. What do you make of this relationship between Benjamin, Jewish culture, and Borges?

R.F.: If you go further into that chapter, which is a rewritten version of an old essay from the nineties, it emerged from an elementary and suggestive ascertainment: the two of them lived in Switzerland at the same time during the First World War, Borges in Geneva and Benjamin in Bern. Borges traveled to Geneva along with his family and his father, who was already showing symptoms of the blindness that would eventually catch up to him. He went to see an ophthalmologist, not realizing they were stumbling into a mousetrap: the war was about to break out, and they had to remain in Geneva for four years. Then they spent another couple of years in Spain. On the other hand, Benjamin fled from the war and moved to Bern, where he had long conversations with Gershom Scholem on many subjects, including some connected to Jewish culture, the Talmud, and the Kabbalah. That was where he wrote what would become his doctoral thesis on romanticism. I wanted to put the two of them in play in the context of certain shared interests. First, the library: Benjamin has a beautiful essay called “Unpacking My Library,” which he wrote from exile. In this text, he tells how his library suffered the vicissitudes of displacement and how he acquired certain books even while being dispossessed, how he gradually assembled this library, going to old libraries, old bookstores, how you get to know a city precisely by searching for these objects—in this case, books. Benjamin establishes a relationship between the library and the act of walking the city; he also sees, in the library, the idea of infiniteness, the idea of the universe. And, obviously, these are 100% Borgesian themes. A point in common is that Benjamin built a theory around this through the figure of the flâneur, and his interpretation of nineteenth-century Paris is directly linked to the notion of flânerie, the stroller who wanders the city. And Borges made walking Buenos Aires almost a work of art.

M.R.: It’s interesting because, when you take away the Borgesian peculiarities of his texts, what you find in him is the stamp of the Southern Cone, which he shares with Chilean, Uruguayan, and Argentine writers. They’re writers with very little concern for Latin America in a more general sense. They’re writers who discover Latin America and, at the same time, are perfectly adroit with the literature of their own countries and with the literary traditions of other languages.

R.F.: That’s true. That’s what makes them different, for example, from a significant number of the canonical writers of Colombia, Mexico, Bolivia, or Brazil, who are more immersed in their country’s own tradition. The literature of the Southern Cone produces a blend between a clear rootedness in the problematics of one’s country’s language and national vicissitudes, along with a strong European education, for want of a better word.

M.R.: Does it also have something to do with provinciality? A way of being cosmopolitan at the far ends of the world?

R.F.: Yes, and at the same time, a way to break away from a debt to other literary traditions, we might say. These authors’ cosmopolitanism does not imply foreignness from their own homelands; it is, in fact, a way to reread yet more intensely their own relationship to their land and their own language.

M.R.: I have another question on a matter of style. I know the book was written through a method you have patented as “happy appropriation” (laughter). Nevertheless, it is interspersed with segments written in italics that are literary, narrative, and even poetic, which examine a character who is never named. My question is: what is the function of this strategy?

R.F.: It came to me all of a sudden. My expressive wheelhouse is the essay, and I see the essay as a literary journey. It has that amphibious disposition: it carries with it the poetic, the narrative, the literary, experimentation, the unfinished, and, at the same time, it is built out of what we might call research work, scholarly work, etc. I believe there is a great essayistic tradition in our countries. And, from my perspective, the essay always allows one’s stylistic concerns to flow. What’s more, I believe style is decisive when transmitting an idea, and is antagonistic to monographic reductivity or the “paper.” I felt the need to interrupt the essay’s more classic narration with a somewhat fictional interference. To place Borges—placing myself, in imaginary terms, within Borges—in Geneva, readying himself for death.

M.R.: Of course, I coudn’t not mention it. I was very curious about that, because it brought to mind a connection with Hermann Broch’s The Death of Virgil.

R.F.: Yes, certainly. And I’ve always been impressed by Broch…

M.R.: Of course. And you’re seeing this character about whom you’re talking from the outside, but then you start to see him from the inside.

R.F.: It might also be that there was a certain need, at some point, to camouflage what I was writing as Borges himself, as if that more narrative moment were a way to insert Borges into what I was writing about Borges. Even when I was rereading what I had written and discovering the brutal presence of those adjectives and nouns so proper to Borges, I thought I should wipe away some of those more eloquent idioms, but I felt that was almost impossible because I would end up giving myself away.

M.R.: I’d like to conclude this conversation with a more personal question. As a reader of your book, I might say, “I see this, I see this other thing, I liked this, I disagree with this other thing.” But my question is: how would you like this book to be read?

R.F.: As one reader’s happiness. I cannot conceive of my life without its neverending, oceanic journey through books. I would love for this book’s reader to perceive it as a celebration in uncertain times, in times of reactionary ignorance, and as a celebration of that ever-open journey that is the journey through literature, through writings, through libraries. For me, the only real homeland is the book. And I think that’s in play when it comes to Borges. In the most Benjaminian sense of the word, this is perhaps a book of nostalgia—that is, not remaining imprisoned in a closed-off, paralizing way in a wonderful past experience that will never return, but rather a permanent updating of those unique moments that reading gives you. That’s where the reader’s complicity lies.

M.R.: Ricardo, many thanks for this wonderful conversation. I’ll just close by inviting all our readers to read La biblioteca infinita: Leer y desleer a Borges by Ricardo Forster.

R.F.: Thank you, Marcelo. The interview has been a pleasure and an honor, I’ve really enjoyed it. And, in the end, we keep on moving and insisting that these things matter.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon

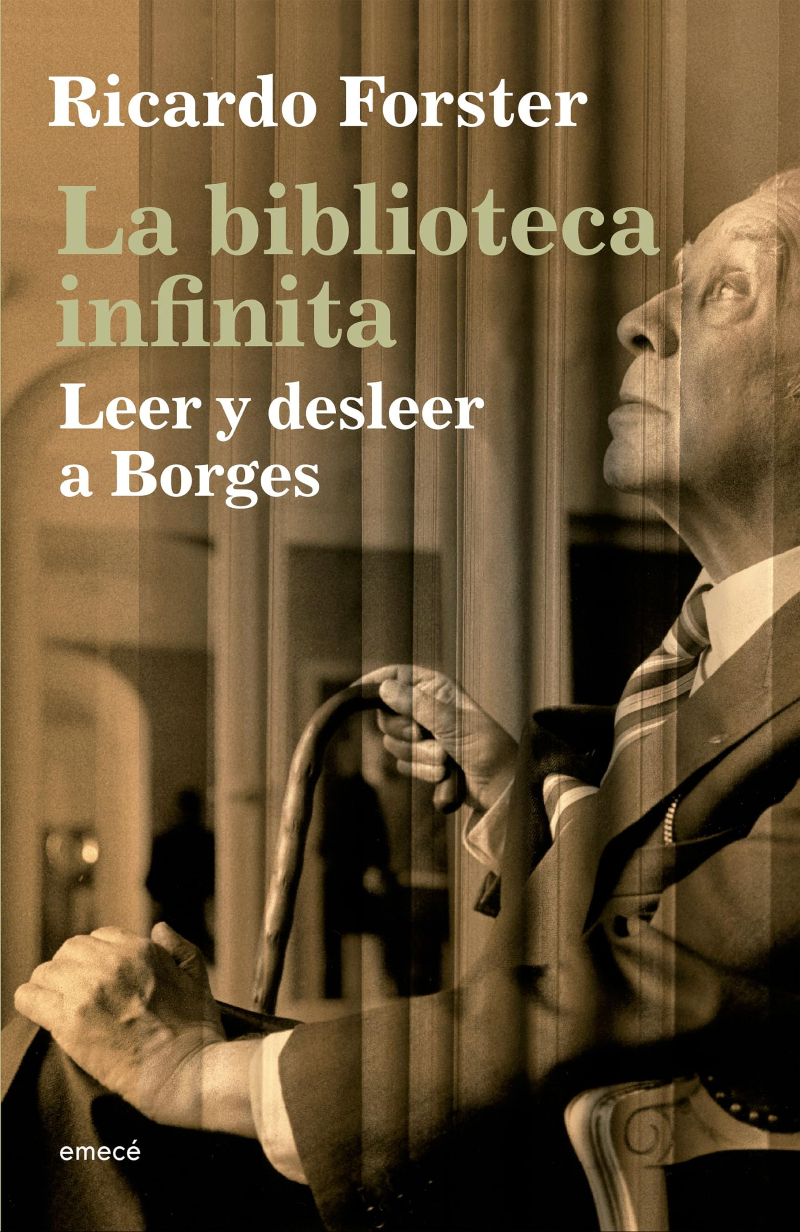

Photo: Argentine writer and philosopher Ricardo Forster.

Ricardo Forster

Ricardo Forster