Najua nitototl: niptatlane noyoltipan.

“Now and then I walk backwards. It is my way of remembering. If I only walked forward, I could tell you about forgetting.”1 This is one of the best-known poems by the masterful Ak’abal, not to leave aside other poems written with the same quality and the same philosophical weight born of the K’iche’ culture. To speak of this poet’s verses is to return to his writer’s personality, to his living face, his white hair poking out from the edges of his cap or his bandana decorated with rivers of thread sewn by the hands of artisans.

To remember him is to hear, once again, his “Birdsong,” where the poetic voice par excellence speaks in K’iche’ and where there is no room for translation (or self-translation), as there is in other poems of his. If birdsong were translated, it would lose its strength, its color, its poetic sound. This poem, it seems, is the first of its kind, in which everything is put together through sound. This is one of the greatest teachings left behind by the greatest poet of the indigenous languages of America, whom fate did not favor with more time to write and create new worlds: worlds proper to a K’iche’ vision little-known within contemporary literature.

One might imagine many things of Humberto Ak’abal, but I only imagine his gait, his youthful speech, and the journey he took to become a poet, because being a writer from a place like his means being nothing. In isolated towns like his, the only ones who enjoy recognition and privilege are teachers, engineers, and lawyers, although the latter, after a while, are branded as the most corrupt of all because they take advantage of people. There are other highly prestigious callings, such as that of the traditional healer or medicine man, but not that of the poet, because poets are nothing more than poets; all they know is how to talk like the elders. Returning to the poem about walking backwards, in Nahuatl the word “to remember” is nikelnamike, “I remember it,” which means “I find it in my chest,” down there, under the ribs within that flesh where the heart lies, where we come to encounter another person or another moment in life. To remember means to live or relive something from the heart. In other linguistic variants of Nahuatl, “to remember” is timitsyoltemoua or nimitsyoltemoua, which means “I seek your heart.” Here, to remember is linked directly to the heart. In other words, to return to the heart is like walking backwards, like observing and reliving that which is left behind.

To remember is to return to the life of a child with no schooling besides the schooling of his parents, his grandparents, and the advice of his people; I would say our first school is our household, our home. “Formal” education is a modern invention in which the only one who truly knows anything is the instructor, the schoolteacher, who might be well educated or not, but who is a schoolteacher just the same, bearing the banner of wisdom with the aim of wiping out a language and imposing Spanish, the language of power and the state. Our poet lived through this and watched it happen with both scorn and appreciation. He tells us it was hard for him to learn Spanish, a language isolated from his people, his parents, and the children of his time. The learning process was slow: first understanding, then reading, and finally writing, until he could think as a poet and write from a language foreign to his origins. Nonetheless, he learned it well, and all this written learning brought him to poetry. Sometimes it is necessary to turn to the past, because his journey to the lettered world has a great deal in common with the journey of the Mexican writers who started writing out of nowhere and who, instead of going to school, first became familiar with working in the fields or at some other calling, but never that of letters, never that of reading or writing, because as children there were no books to be found: just work and animals to take care of.

I like to imagine Humberto Ak’abal as a Mexican. Mexico and Guatemala have a great deal in common. They have the same language, the same river, the same political situation—they often resemble each other, at least. Their poverty, their racism, their discrimination, their mistreated people, their forgotten peoples, their deaths, their wonderful embroideries and their philosophy are almost the same. We are divided only by a geographical barrier that divorces us from one another, at least as human beings; animals move from one side to the other undivided, because it is the same land in the end. Ak’abal knows this better than anyone, breaking through the barrier of the “nation” with his birdsong. The birds have no nationality. They can fly wherever they like. Here is another poem of his about birds, which could also be dedicated to politicians, or to anyone you like:

The birds

sing in full flight

and in full flight they shit.

I stare at them,

and my gaze follows

until the string

my vision has given them ends.

How I would like to be a bird

and fly, fly, fly

and sing, sing, sing

and shit—with pleasure—

on some people

and some

things!

Translated by Miguel Rivera with Robert Bly

The similarities between Mexico and Guatemala are striking. Perhaps our literary situation is also the same: writers to whom no one pays attention, writers who don’t exist in libraries or bookstores whether their work is good or bad. They don’t make it to these places because they are reserved for the privileged writers who write in Spanish, in a monolingual format. Thinking people, they say, who are concerned only with writing and being recognized in literary circles, but who are unconcerned with the lives of their people or native cities, and unconcerned as to who might translate them. They don’t have this concern with reaching the soul of their people in their own languages, if they have their own languages—a language other than Spanish, that is. In an interview with Hermann Bellinghausen—friend, promoter, and great reader of Mexican literatures—Ak’abal took pleasure in the literary life of Mexico because, day by day, the number of authors writing in their indigenous languages was increasing. This is a matter not just of writing in a certain language, but also of joining together with others who write from the most distant corners of their countries. Humberto also dreamed of seeing this flourishing in his native Guatemala, but he was not to witness the arrival of this movement or this recognition of modern literature, different from what existed at the time. He was not only a pioneer within this young literary movement; he was also the founder of a different literature, welcomed with open arms in Europe, Latin America, Mexico, the United States, and other countries where his texts have been translated into different languages. Personally, I can say that Humberto Ak’abal is the finest poet of the indigenous peoples of America. We might go so far as to say that, up to the present, he has been the finest poet of all our peoples. I do not say this to close off the possibility of welcoming new writers, excellent writers who might transform the life of new literatures; in fact, we all hope for the arrival of more than one such writer to reinforce our literatures.

Life treats some of us unfairly, such as Humberto Ak’abal, Carlos Montemayor, Isaac Esau Carrillo Can, Rocío González, my cousin Santos Cochine Meza… Many whom one would still wish to meet in person, to converse with, to spend time with, to eat with, and perhaps to strike up a close or distant friendship with. But they are no longer here, and it is hard to return to the color of their eyes, their laughter, their good or bad advice, but their advice nonetheless. Ak’abal was a simple man. A wise K’iche’ man, whether a poet or not, and undoubtedly a man of great thought. I must say, I am put off by bigheaded artists and by bigheaded men in general; I think their egos have grown too large and they are no longer capable of dialogue. To my mind, Ak’abal knew how to distinguish between these two phases: he knew how to be an artist in a given space and time and also how to be a person.

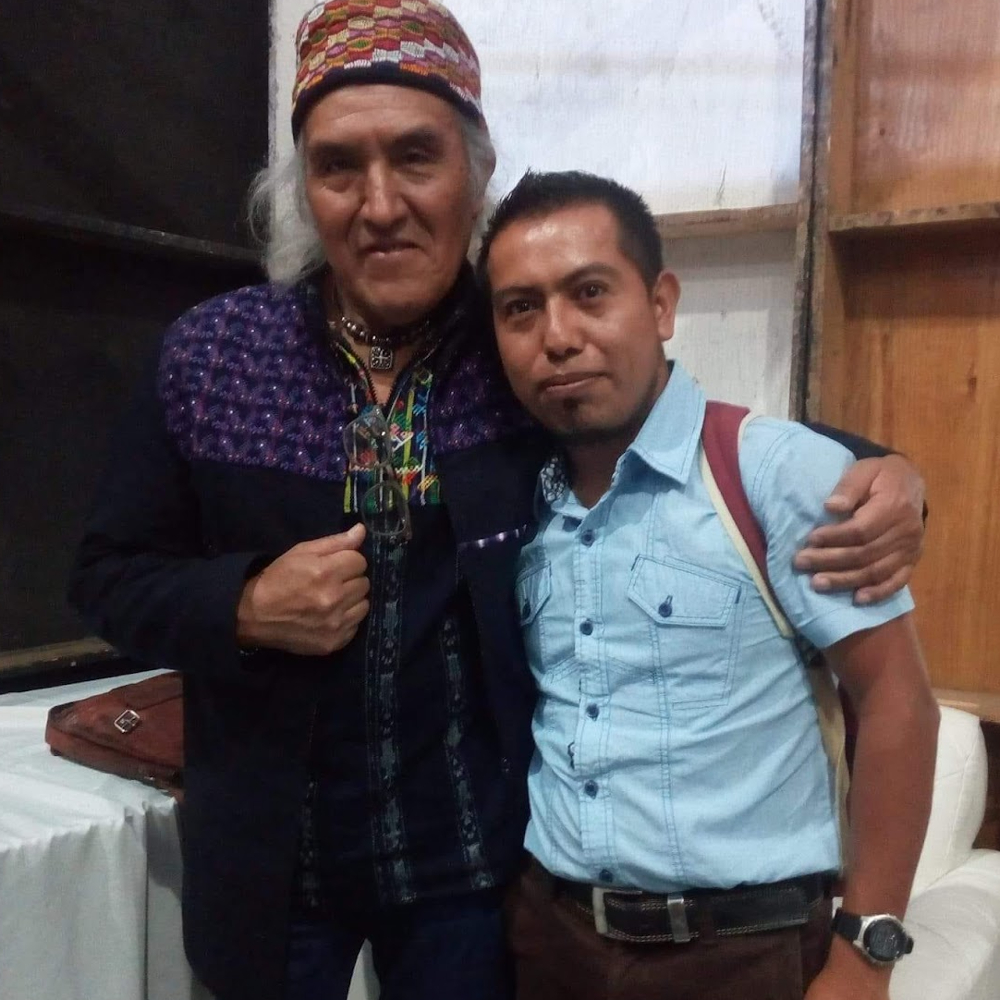

In 2018, he came to read in Mexico City for the last time. The curious people passing by in front of the big bandstand stopped to listen to this man with a grandfather’s voice and profound philosophical thought. I don’t remember which poems he read on that rainy afternoon in the zócalo, but there we were among the crowd, listening to him read. Minutes before, we were on that stage ourselves, reading some of our poems; beginner’s poems, of course, compared to Ak’abal’s words and verses. I don’t remember all the many poems read from that stage, but I do remember when he read that intense poem called “Birdsong,” when all the birds were within the poet’s voice. Each whistle and each song was a call of joy, a call of sadness. Each ear deciphered the song in its own way, and this was the best translation.

If he were still alive, Humberto Ak’abal would be perhaps the first indigenous poet who might aspire to the highest honors given in the literary world, such as the Princess of Asturias Award or the Nobel Prize. In the American continent, he would be the first candidate because he was an active and visible poet, but beyond his personality, you could hear his thought, concentrated in his poetry. I once met with some other Mexican poets who write in indigenous languages and this question came up again: if there exists a truly great poet in the indigenous languages of Mexico or of this continent in general. In truth, it was not hard to choose one, for it is true: there are many poets, but none with the clarity nor the aesthetic quality of Ak’abal.

His work will be preserved for the coming generations of Guatemalan poets, K’iche’ and Mam poets, and those who write in the other languages of Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Bolivia, and the other countries of this continent where new writers are emerging in indigenous languages. For as long as I live, I will say his name and share his verses as far as my wings can spread, because Humberto is like smoke: he “does not dissolve / even in water.”