There’s a buzz about Colombian children’s literature at the moment. The field is currently host to a daring and diverse crop of exquisitely-produced books of high literary quality, mostly by homegrown writers. And, to a large extent, this abundance of riches is due to publishers’ commitment to one genre in particular: the picture book. A brief survey of what’s currently on offer shows that independent publishers are leaning heavily in favour of all kinds of illustrated books, including comics, graphic novels, fanzines and, of course, picture books. These genres have enabled the independents to carve out niches for themselves in the publishing world. Their daring has been rewarded by growing readingships, helped along over recent years through a happy alignment of cultural and social factors: a thriving independent scene, pro-reading policies and promotions, and the ascent of digital platforms. What’s more, these elements all mutually reinforce one another to form a network; combined, they have set the stage for Colombia’s picture-book boom.

Dipacho, Antonia va al río, Bogotá, Cataplum Libros, 2019.

In this article, we will look at the publishing environment within which this boom has taken place, and we will also take a closer look at some of the picture books that have been published in recent years. But first, some remarks on genre. Quite a few studies define the picture book as a postmodern phenomenon, which emerged thanks to the professionalization of the publishing industry:

The diverse array of different formats, papers, techniques, and finishes involves a series of decisions. The picture book is a genuine product of the publishing process since each one is the result of a chain of decisive contributions. How the resulting set of signifiers are arranged will ultimately determine the meanings that the reader will be able to construe.1

The picture book is one of the genres with the greatest variety of forms, dimensions, papers, textures, paper cuttings, and printing techniques. It emerges out of the creative interplay between these formal elements (along with the text and illustrations). Picture books are created cumulatively as a result of a series of different contributors who each intervene at a different stage in the process: “Some define it as a true ‘industry’ genre, the product of the collaborative work between author, illustrator, designer, and publisher, with each contributor doing their best to ensure that the whole can shine, but above all to carve out a space for the reader of the text to inhabit.”2

Tumaco,

Bogota, Rey Naranjo, 2014

Cómbita,

Bogota, Rey Naranjo, 2019

Cazucá,

Bogota, Rey Naranjo, 2018

Both of these definitions end by alluding to the readership, because it is the readers who interpret, give meaning to, or simply dwell with the picture book that has been created through a collective effort. The true picture book is a work of art, an expressive endeavour that gives rise to an aesthetic and literary experience through the interplay between words, images and design. The use of the term “true” here is not intended to enforce strict limits on the parameters of the form, but rather to contrast these artifacts with the often rather formulaic picture books that the larger publishing houses have started to produce.

The picture book is an inherently hybrid genre where different artistic languages converge: literature, drawing, painting, cinema, design, theater, and music. It is a polyphonic mode of narration. Nothing is left to chance in an authentic picture book: each element is potentially a piece of the text and is there to be interpreted: the size, the binding, the texture of the pages, the flyleaf, the front and back covers. These all reflect decisions taken by the creative team on the road to bringing the work of art into being. Other studies define the genre in terms of this “made,” even sculpted quality.

The picture book is a mode of expression whose basic unit is the double page, on which images and text are inscribed in an interactive fashion, with a narrative or thematic thread linking one page to the next. The great variety of ways in which these links can occur derives from the multiple different ways in which the text, image, and overall format can be organised.3

The materiality of the picture book allows for aesthetic and literary experimentation. It is the most malleable and flexible form of children’s literature, a favorable terrain on which to play, try out ideas, and take risks—and not only for the creators. It is also a way for readers to experiment, a rupture in their traditional reading practice. This makes each picture book a work of art with its own self-generated language, constituted in real time and from one page to the next. And it means that each reading is unique.

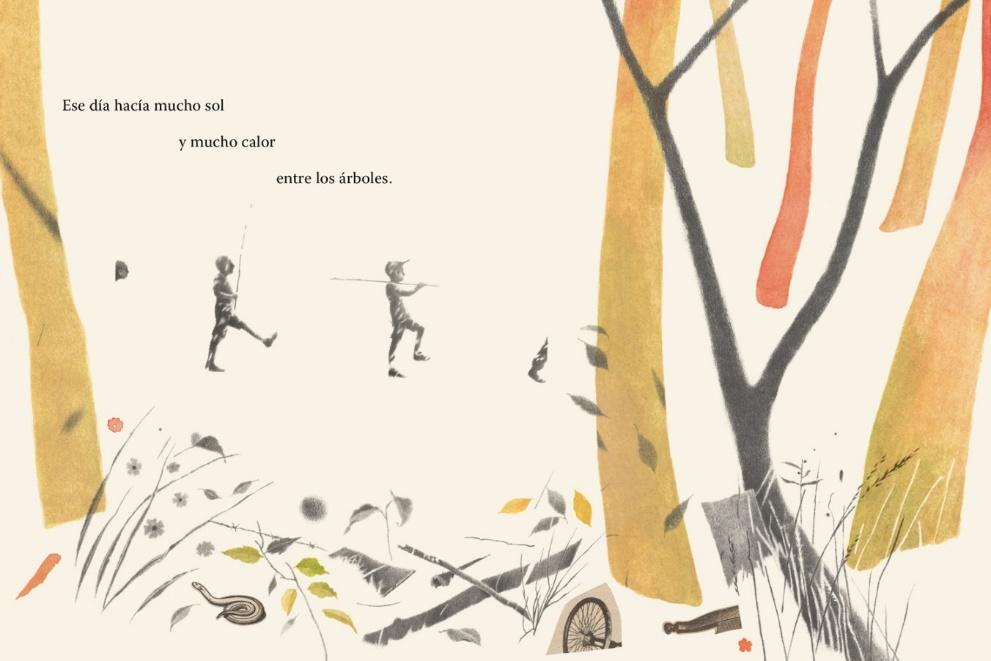

Castaño, Samuel, El incendio, Medellín, Tragaluz Editores, 2020.

The Independent Publishing Scene

The last ten years have seen the emergence of several independent publishers, of new digital technologies, and of new academic programs in publishing. Together, combined with a gradual increase in state support, these factors have given rise to a kind of democratization of the publishing industry, opening up the field to new ideas. The consolidation of an independent publishing ecosystem has diversified the kinds of books that are produced in Colombia. There is an abundance of high-quality literary works by Colombian authors that broach social, political, cultural, and historical themes. What’s more, the modernization of manufacturing processes has meant that the “book as object” has acquired added meaning; the material form of a book in itself tells a story, and so publishers put effort into ensuring that their unique identity is visibly manifest in each book’s material details.

Muñoz, Juliana & Dipacho, El vuelo de las jorobadas, Bogotá, Lazo libros, 2020.

With picture books, independent publishers are taking a chance on art, on works that are conscientious and critical, and on manufacturing processes that are slow and careful. They’re siding with creative freedom and experimentation, in the hope of eluding the Russian roulette of a marketplace that only has time for best-sellers. Independent publishers have found an unusual degree of freedom with the picture book. The key players are Albaricoque Libros, Ama Lita Books, Babel, Cataplum, Click+Clack, El Salmón Editores, GatoMalo, La Jaula, La Madriguera del Conejo, Lazo, Luabooks, Milserifas, Monigote, Rey Naranjo, SM (which unfortunately closed its doors in Colombia in 2022), Siete Gatos, and Tragaluz.

Some publishers have adjusted quicker than others; each case is different, and just as there are no formulas for picture books, there are no fixed templates for the publishers that produce them. Each one has its own identity in terms of form, content, and guiding spirit; in other words, the books they publish strive for an overall coherence—sometimes even an ideology. They have developed publishing identities that are recognizable to readers, like a kind of particularly ambitious literary worldbuilding. They have also crossed boundaries between literary genres, countries, and ages. Breaking down the illusory, market-dictated age barriers in the publishing world has been particularly significant. The picture book has reached readers of all ages and has jettisoned the idea that it is an exclusively children’s genre. The best picture books are works of art, rendering obsolete the suggested reading ages that sometimes appear on back covers:

Age is abstract and, in effect, irrelevant. The fundamental thing is that the language of picture books (i.e. the conjunction of images and words) mobilizes deep, primordial emotions that move people. And the manner in which the genre has evolved has gradually broadened its appeal to adult readers.4

The Power of Childhood in Picture Books

Children’s literature today is dominated by a realist aesthetic. Authors address specific issues that are relevant to the social and historical moment inhabited by their readers, broaching their subject matter in artistic, critical ways. The current prevailing concerns in Colombia include the ongoing armed conflict,5 the abandonment and abuse of children, domestic violence, bereavement, discrimination, the challenges of overcoming gender stereotypes, and environmental matters. The picture book form allows for access to a diverse register of childhood experiences that go beyond stereotypes. This has meant a departure from the tendency to romanticise childhood as a state of innocence and purity, and of dependency on adults for education, protection, and survival. The picture book has played a key role in giving children a voice in the narrative, and not simply in the dialogue. The stories are narrated from the perspective of an inner self that engages critically and reflexively with the surrounding environment and (contrary to what adults prefer to believe) that is keenly aware of the most serious issues. The authors are skilled at imagining other, freer, more rebellious childhoods, with child protagonists who are powerful, complex, and ambiguous. Protagonists with the power to be destructive, but also to create and imagine; with the strength to face pain and with the vulnerability to feel it; with the courage to question the adult world and, above all, with the ability to tell a story.

Chirif, Micaela & Ortiz, Paula, Cristina juega,

Bogotá, Cataplum Libros, 2021.

The power of the child’s imagination is a staple in children’s literature. It’s an endlessly handy narrative device for conflict resolution, but the picture book takes a different, perhaps less instrumental approach. Here, imagination is like a childhood superpower that does not need to be explained nor used to justify the story, a permanent state of being-child that is simultaneously both the world itself and the way in which that world is understood. In the picture book Cristina juega (2021), imagination and play are at the center of the story. The extra layer provided by the illustrations makes us question the reliability of the textual narrative; the ground rules shift and, henceforth, the story must be interpreted from a different perspective that enlists the active participation of readers. Just as childhood contains the power to imagine and create, it also contains the power to destroy, to do away with what exists. Picture books can be disturbing; El incendio (2008), for example, is a story of transformation where the protagonists abandon childhood, setting it on fire. The book begins and ends with images of a burning forest (the pages are coloured entirely in orange) on the hill where the story’s group of friends grew up sharing long afternoons filled with games and mischief. One afternoon, they follow the trail of another group of children, but they never find them. They don’t know it yet, but it will be the last afternoon of their childhood.

There are also protagonists who face adversity, who face hostile, violent, and dangerous environments. And yet, they have the power to move forward, to face life with courage, or to change the situation. Beyond the prospect of a “happy ever after”—which is not really what usually happens in picture books—the narratives have an air of hope that imbues the characters with dignity. Óscar Pantoja has written a series of stories about children living in impoverished parts of the country, where obstacles are encountered on a daily basis. The protagonist of Tumaco (2014) dreams of having a pair of football boots, and his father works hard as a fisherman to attain them. In Cómbita (2019), a peasant girl dreams of being able to ride a bicycle; she tries again and again but repeatedly falls over, until one day she must face her fear to help her father. Cazucá (2020) tells the story of a girl who lives in a very poor neighborhood where there is no water, and has to walk long distances to fetch it by the gallon; the journey home is difficult and comes with the risk of spills. Unusually, none of these books contain any text; they are silent picture books which are narrated visually. The illustrations are two-dimensional, minimalist compositions rendered in vibrant colors that connect the reader with the world of childhood; similar to a comic book, the story is told cumulatively via sequences of vignettes. Another silent picture book is Antonia va al río (2019), the story of a girl who loses her dog, Antonia, when she travels with her family from the country to the city. They have been displaced from their home, and now, having left many valuables behind, they venture into the unknown with just a few belongings, relying on the kindness of strangers for help along the way.

Satizábal, Amalia, Río de colores,

Bogotá, Editorial Monigote, 2020.

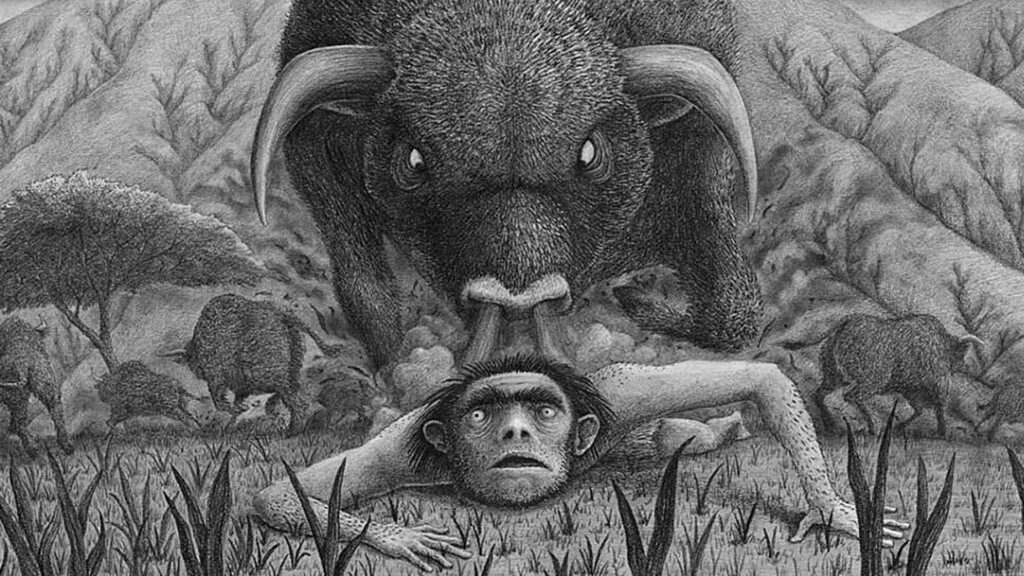

Childhood is the realm of the power of observation, and of the ability to feel wonder at the everyday. Children can spend hours contemplating the routes followed by ants, watching raindrops fall amidst puddles, digging up the earth in search of animals—and then they can question the reason for those things and try to put the answer into words, narrating life itself. ¡Ugh! Un relato del pleistoceno (2022) tells the story of the origin of stories. A tribe of cave-dwellers sets out on a journey in search of shelter for the winter. On the way, they encounter obstacles that threaten their lives and, little by little, the tribe shrinks in number. The protagonist is a little girl who carefully observes her surroundings, the animals, the footprints on the road, the river, and the falling snow; she is endlessly attentive to the world around her. When they finally reach the cave, she etches marks into the stone, telling the story of their experiences. Those cave etchings turn out to be the origin of stories. The black and white graphite illustrations are sublime, confronting us with the immensity of the hostile world of the Pleistocene. The tribe, in contrast, appears tiny, fragile, and vulnerable, though powerful at the same time.

Other publishers such as Monigote, Lazo Libros, Click+Clack, and Ama Lita Books focus on issues relating to ecology and heritage, advocating for the safeguarding of Colombian land and culture. The picture book Río de colores (2020) tells the story of a family of spectacled bears that has been ousted from its natural habitat on the upland plains, and has moved to the city. This story of the migration of a species is also an in-depth exploration of an environmental and political issue. It’s a literary work that provokes curiosity and laughter in younger readers. El vuelo de las jorobadas (2020) is an informative book about the journey that humpback whales make every year from Antarctica to the Colombian Pacific. Both books take the reader on a journey through the Colombian landscape, the better to know it and to know to protect it. The illustrations are extraordinarily well rendered by artists who have their own unique style that drives the narrative and imbues it with layers of meaning.

Yockteng, Rafael & Buitrago, Jairo, ¡Ugh! un relato del pleistoceno,

Bogotá, Babel Libros, 2022.

The picture book is the dominant mode of expression in Colombian children’s literature today; the form serves as a fertile space for creation and experimentation; it offers a “social, cultural, and historical document, and, above all, an experience for children,”6 and indeed for all of its readers, young and old. Are we living through the golden age of the picture book in Colombia? It’s not easy to say for sure. What we do know is that we are witnessing a picture book boom that has been built with the determination and creative intuitiveness of authors, the rebellious streak of independent publishers, the careful steer of promoters, librarians, teachers, and booksellers who disseminate children’s literature throughout the country, and with the boundless curiosity of children and readers who have found in the picture book a place to inhabit the world.

Translated by David Conlon