I’m here, he’s not. Therefore, everything I write about him will be a betrayal. “Betrayal!” Fogwill would say, with that naive use of exclamation points he relished and employed to amuse himself. How to write about Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill, who for me was first Quique, or Kike, as he preferred. How to write about him without stating the obvious, a trap I’ve already fallen into: stating the obvious, one of the many pitfalls of style he rejected: the comfortable cushion of clichés. But everything has its price, and when the abomination of the obvious is taken to an extreme, you must abhor all the rallying cries of the righteous, consciously aware folks, and scorn what seems necessary for the situation in which you detonate your ferocious bomb: you must profess to be against the politically correct, against legal abortion, against gay marriage, against human rights, as the national and popular left understand them. Above all, you must object. Slash open the belly to expose the miserable guts of certain ideas. “Far from the politically correct, stands Fogwill, master of irony, disdain, and diatribe,” says Beatriz Sarlo. No one could ever say that Fogwill spoke poorly about people behind their back. During a round table at the Book Fair, I once heard him shout into the microphone to a colleague, who was struggling to stand up with his Canadian crutches, that he considered him the best lame writer of Argentina (let’s just say there were others).

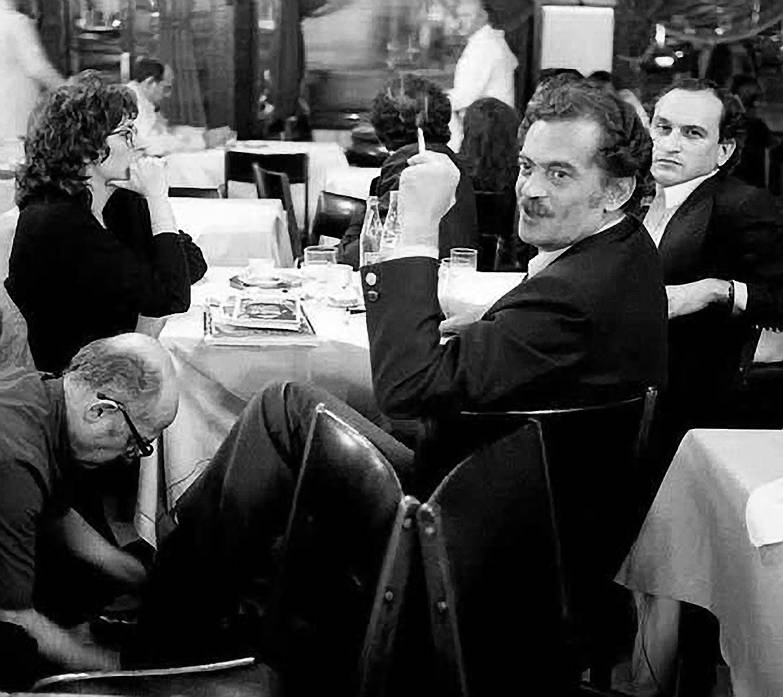

Fogwill spoke the truth like a child; he was a spoiled brat, and he knew it and liked being a holy terror, telling the truth without a filter, without the wisdom or self-preservation of adulthood, revealing it with that gaze of his—always strange, wise, cruel, and infantile, saying what shouldn’t be said, seeing everything as if for the first time, and speaking his mind, which is why he was such a good writer, such a great poet, and so unbearable for so many. For shock value, yes, but the bourgeois has become so used to scandals that it’s become more and more difficult to shock them, and more risky. And that’s where he seemed a bit like Borges, perhaps. Like that Borges who could go to the extreme of praising slavery just to upset his interviewer. He was like Borges in the way he constructed his public persona, which complemented his literature, a character that was always, in some way, much more conventional than his true self. His revolutionary writing always led the reader down unexpected roads, and sometimes, precisely because they were familiar and well-traveled, in that sense (but only in that sense), Fogwill resembled Kafka, in his willingness to employ the most banal devices as a means to an end (but not an ending), to an always surprising conclusion, a trap always set to astound, startle, jab, and pursue his readers. Fogwill admired Aira, Lamborghini, Perlongher, but his own writing went down other paths, and was original in a much more subtle way, much less violent and explosive than the writers who interested him. He didn’t avoid emotion, he wasn’t hermetic, he wasn’t brazen. He was Fogwill.

Because I value an opinion that comes from outside the muddy waters of Argentine literature in which we wallow (to borrow from the tango “Cambalache”), because it expresses what I’m saying, but from a European perspective, I’d like to cite Branko Andjic, a Serbian writer and critic, and specialist in Latin American literature:

Fogwill was right when he dropped his first names—Rodolfo Enrique—because he was well aware that he was one of a kind, like Prince or Madonna. However; his flair for marketing never led him to publish feeble and fleeting bestsellers, nor did it take him down the most trodden and predictable paths of fiction. He should be posthumously awarded for artistic bravery, for always seeking creativity and experimentation. His best work remains a warning to writers that playing it safe, with humble artistic ambition, doesn’t pay off in the long run.

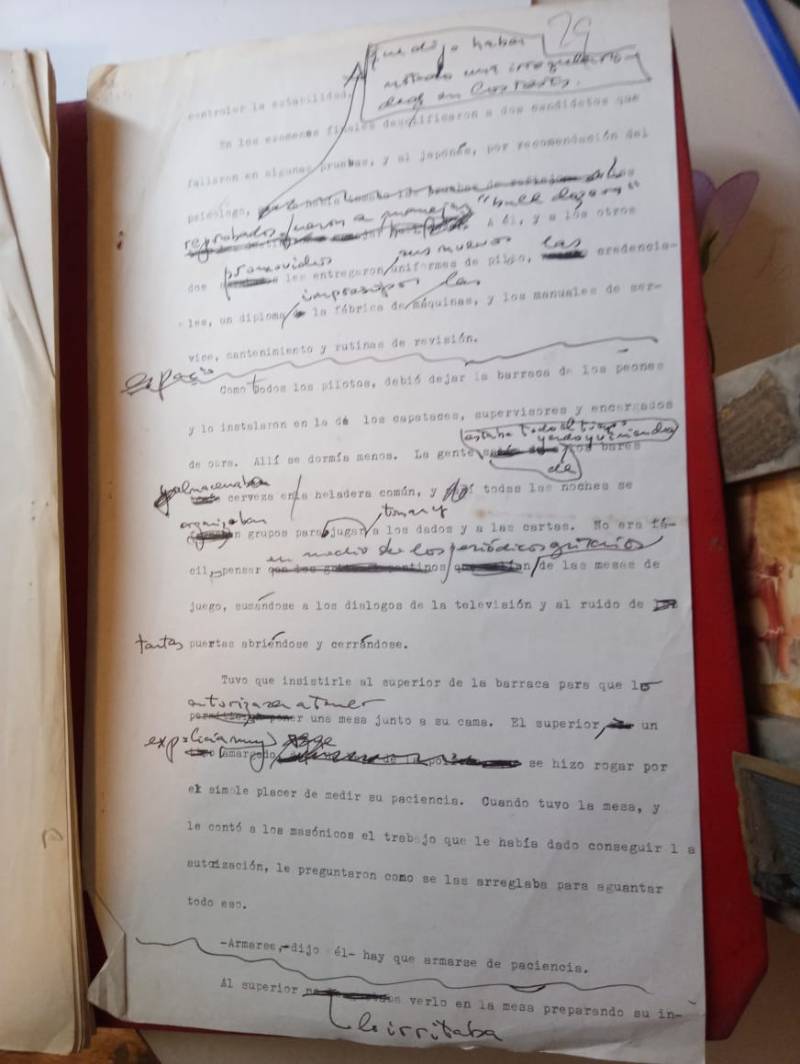

How long did it take Fogwill to write Los Pichiciegos, that novel about the Malvinas War so indispensable to Argentine literature? According to rumors at the time, barely a week. Today, they say it took three days. Three days without eating or sleeping, fueled by cocaine alone, pouring words into the typewriter, frenetically. We were friends at that time. Ever since we met, we’d read each other, and Fogwill’s original manuscripts turn up all over my house, many unsigned, all of them recognizable, with that peculiar way he had of making good use of the page: complicated drafts, full of revisions and crossed out words, which he’d have someone type out, single-spaced, in an enclosed box, to the right. (I should turn them over to someone who’s studying his works, but I don’t want to, I don’t feel like it, something Fogwill would understand and appreciate.)

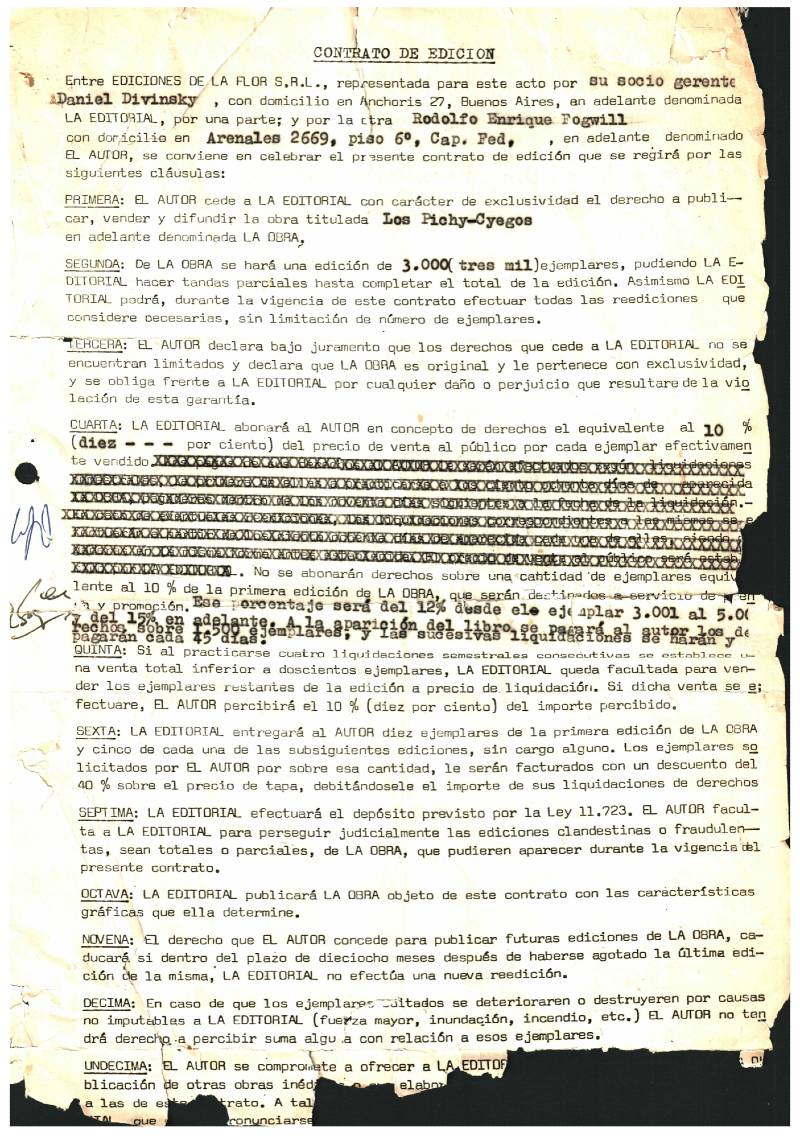

I don’t know how long it really took him, but I know I read it before the war ended. Los Pichiciegos has always been a dazzling novel, shining a glaring light that slightly blinds whoever looks right at it; a novel that’s best read out of the corner of the eye, with dark lenses. It wasn’t easy for him to find a publisher. Fogwill had already won a competition sponsored by Coca Cola that would’ve allowed him to publish his amazing first book of short stories, Mis muertos punk, in the prestigious and successful Editorial Sudamericana. But, inaugurating a Fogwillian tradition he’d never abandon, he had disagreements with his potential editors and ended up publishing his book in his own, newly minted editorial house, “Tierra baldía.” Los Pichis landed on the desk of one editor after another, and Fogwill chose to argue with each of them. He came to be admired and feared: a dangerous verbal terrorist. For some mysterious reason, he was able to come to an agreement with Daniel Divinsky, who, at that time, had recently returned to the country from a long exile, and who always regretted initiating a relationship with such a contentious author. Not even the historical honor of being the first editor of Los Pichiciegos made up for the insults Fogwill slung at him, blaming him for the commercial failure of his book.

Could that novel have been a commercial success? Perhaps. It was the first novel ever published about the Malvinas War. Fogwill needed the money. Divinsky was reassuming, with a certain degree of insecurity, the reins of Ediciones de la Flor, which had been kept afloat only by those writers publishing graphic comics. Could it have been a success? Perhaps, but only perhaps. After it was published, I remember giving the book to an uncle of mine, an avid reader, who returned it to me disappointed, without sharing my enthusiasm. “It’s very cold,” he said to me, and maybe his opinion was the explanation for the inexplicable. “And there are no heroes!”

There are no heroes. That’s exactly what it’s about. Throughout Fogwill’s fiction, emotion is carefully restrained, with barriers. It’s not cold, although he likes to pretend it is, to disguise the tenderness that’s usually present, although he would have preferred that I didn’t even mention it: sentimentality is the worst sin a writer can commit. And above all, there are no good guys and bad guys, just people, but no heroes. The only hero that performs acts of bravery is language.

Recently, I just finished reading, while I’ve been thinking about this text, a novel of his that I’d never read in its published form, En otro orden de cosas [In another order of things]. I have the original here, almost illegible, from when Kike, owner of the company Facta (a marketing agency) and Ad Hoc (an advertising agency), had transformed himself once and for all into Fogwill, and had no company or money to have his original manuscripts typed. Back then, he called it Un orden de cosas [An order of things]. Few books reflect their author as much as this novel, not the best Fogwill novel, but one that bears a strange resemblance to him, the way a dog resembles its owner. A book about the country, about failure, about language. Fogwill pursues words, torments them, takes them to the extreme, where language intersects with philosophy. With his sublime ear, he tackles platitudes, figures of speech, expressions void of content, personal effects (the title of that work never published with that title). “And it doesn’t even seem like a dream. It seems real, like the plastic cartridge inside a pen you hold between your fingers as you write. That hexagonal prism ending in a ballpoint short on ink: is that real?”

We read each other. I remember the night he read his first stories to me. Fogwill had a beautiful deep voice and was studying German so he could sing lieder. But I wasn’t impressed by the stories, not that they were poorly written, but they seemed like attempts by an amateur. I was twenty-three years old, ten years younger than he, but I was a habitual reader, my library was brimming with fiction, while his was stocked with volumes of essays, philosophy, sociology. A would-be story attributed the power of music to moonbeams. The other one, “The Mustard Tree,” told the story of a quest that ended up transforming the one searching. I remember it because I liked the last sentence. Ants were devouring the protagonist: “The words organza and spasm, came to mind. He didn’t know (or didn’t want to) understand their meaning.” Disregarding the allusion to orgasm, I found the last sentence to have a Borgesian cadence.

Where and how might this poem I’m about to cite from the original have been published, bragging, of course, about my friendship with Fogwill, about how he chose me as a reader. I have no complaints and nothing to brag about, he used to say whenever someone asked him, how are you; I don’t have friends, he’d say, whenever the opportunity arose, and it wasn’t true, he had friends who loved him a lot, but God forbid you talk to him about that impossible and hopeless word, that trite, terribly boring love. And yet:

Forms that rise

Only to fall and sing

Only to stumble

And plant feet firmly on the way

The son:

Trace on the horizon

Blurred upon naming him

0

One look at the son

The son falling

Him sleeping, breathing

Dreaming, on the threshold

Of his resounding song

And the truth is, Fogwill didn’t complain, but he did brag, despite everything, about his conquests, his choices, his diverse knowledge, it’s all there, in his books, his affinity for knowledge, with the perception of what hides behind the obvious, and the awareness of what’s to come, and also what’s apparent, sociology, philosophy, aeronautics, consumerism, microbiology, numismatics, everything Fogwill knows about is all there, to the point that, at times, we forget about his characters, their story, when in the midst of the plot, the author himself emerges, and his readers ask in amazement, but how does he know so much, why does he know so much? He was Google before there was Google, says his disowned friend Silvio Fabrykant, who also happens to be my husband, from the start. Fogwill knows everything, which is to say, nothing. Where are you going, Fogwill? All over the place at the same time. To all parts. Parts of everything.

And then there’s the tenderness, the passionate love for his five children. I didn’t get to know the last two, by that time we had drifted apart, but I did know the first three. When one of his boys came to spend a few days with us at Pinamar, at age fifteen, Fogwill told me I didn’t need to feel responsible for anything, that his son could do whatever he wanted; if he wanted to pick up an old pervert on the beach who’d pay him to suck his cock, that was up to him. But he did ask me this: please… don’t let him go horseback riding. Of course it was infinitely more likely the kid would want to ride a horse than be interested in sucking the cock of an old pervert, but how could Fogwill admit he was afraid his son might fall off a horse, a normal, common fear of an ordinary father…

When his daughter Vera, a talented and award-winning actress, film writer, and director, was interviewed in Cuba, Fogwill sent me an email with the published feature story attached. He was furious and full of righteous indignation because his ungrateful daughter hadn’t mentioned her mentor Alberto Ure. The spectacle of his anger was the only way he could conceal (but not for me) how pleased, excited, and proud he was of his daughter’s success. Like any father.

In his final years, his public persona nearly devoured the person we had known. Without anything in particular coming between us, Fabrykant and I started to distance ourselves from Fogwill. One night, we ran into him at an awards ceremony, and I told him that we missed him. I miss myself too, he responded, and I went away a bit sad: a clever phrase had become so important to him that it wasn’t worth considering other possibilities.

Ten years have passed since Fogwill had the poor taste to up and die. The right moment to dedicate to that talented, daring trapezist of words, forever risking life and limb with a triple somersault, this text from my Fenómenos de Circo [Circus phenomena]:

After so many years, the trapeze artist can’t ignore how he repeats himself, plagiarizes himself. This fact upsets him, as it would any artist. In search of originality, he leaps into the air without a net, without a safety line, and finally without a trapeze. But what’s a trapeze artist without a trapeze? Nothing more than a bloody, blundering heap on the sawdust of the circus ring, and even at that, what a shame, nothing original.

Now that I’m here and he’s not, now that all is betrayal, I can truly have the luxury of saying, without having to suffer a clever comeback, Quique Fogwill, your friends miss you very much.

Translated by Rhonda Dahl Buchanan