what is the most fragile thing in the world

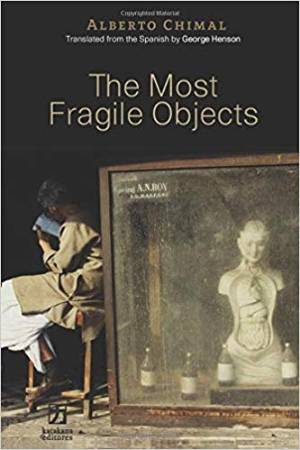

From The Most Fragile Objects

Alberto Chimal

The Most Fragile Objects, Chimal’s first novel published in translation, tells three stories (maybe two, or just one) of people living secret lives in early 21st-century Mexico. They seem to indulge in wanton sex and power fantasies. But is everything what it appears to be? With a style that never resorts to titillation and a plot structure in which the factual and the dubious chase each other, The Most Fragile Objects is an unusual, dark take on the themes of power, love, imagination, and freedom.

The Most Fragile Objects, Chimal’s first novel published in translation, tells three stories (maybe two, or just one) of people living secret lives in early 21st-century Mexico. They seem to indulge in wanton sex and power fantasies. But is everything what it appears to be? With a style that never resorts to titillation and a plot structure in which the factual and the dubious chase each other, The Most Fragile Objects is an unusual, dark take on the themes of power, love, imagination, and freedom.

Available now from Katakana Editores.

29

Mundo is “Latour’s ugly brother, his pathetic, detestable double”: his property. As a rule, he lives naked and curled up in a ball, next to the kitchen door; it is no exaggeration to say that he is an animal. In addition to the usual treatment, he’s received (every Friday, Sunday, and Tuesday since coming into Latour’s life) additional torture, meted out by the cruelest of masters. One can’t but feel pity seeing him raise his head—dirty and covered with matted hair, almost always full of every imaginable filth—when he hears his master’s footsteps. It’s even more heartbreaking to see him run on all fours, rub against Latour’s legs, beg for his attention, or at least try, with rasping, inarticulate moans.

“Idiot!” Latour yells, and Mundo answers back:

“Idiot,” without abandoning his position or caresses, then going on with a hundred more words, in a dozen languages, which Latour taught him and that describe him. Most are from languages he doesn’t even know—kundel, which means “mongrel” in Polish, kichigai, or “imbecile” in Japanese, and achterlijke, Dutch for “retarded”—but every word is heard in a clear and resounding way, as if they were made of glass or metal.

30

“What a horrible thing,” says the actress. Nervous, she lifts her glass to take a sip and almost spills it.

“There are better ones.”

“Better?”

“Of course. One should never overestimate beings like this. Look what a beast. He’s carrion.”

“What are you talking about? Aren’t you supposed to be…? What is he doing?”

Latour enjoys the woman’s confusion so much that he doesn’t answer immediately. Instead he deigns, for the first time in the whole conversation, to look down, to see what Mundo is doing.

“Don’t pay him any attention. He loves being mistreated. He takes pride in it. Allow me.” And Mundo doesn’t quite manage to lick the shoe that kicks him in the mouth.

31

Occasionally, Mundo is content to do nothing, to let time pass. Then he plays at suspending his thoughts and just being an animal. He doesn’t try to name the objects that surround him in the house or recognize anyone who isn’t Latour: this way everyone looks the same, imprecise faces, weak, incomprehensible voices. Someone walks up and pricks him with something. Mundo falls asleep. Later he wakes up and is somewhere else, but he attempts to forget his awareness of the fact and merely surrender, like an animal, like before the stranger came to stick him.

32

Latour writes, in pencil, on cream-colored paper: Yes, Latour is perverse; perversity is a virtue. On the scale of things, skill and sincerity are rarely equal to those things that his soul’s nature recognizes.

Latour hits hard and knows how to hit in places that hurt. Latour knows how to subjugate and order.

Latour believes that everyone would like to give orders, and those who deny it are merely afraid, aware of the nothingness of every being and every effort at living, or possess an even greater desire to obey, to disappear into someone else’s will.

The beings that are his property are always awaiting, in need of his orders, his fury, and his rare queries. But Latour doesn’t need them. More than once he’s killed them, has disposed of their bodies and continued with his own life.

With Latour, every story is true, as are all the tales of pain, torture, restraints, accessories, appliances.

Latour isn’t the terrible god his slaves worship; rather something higher: different.

And Latour is simple: he knows that all his games are useless, a new ugliness in that design that has always been horrible and is, as always, devoid of meaning.

He then tears up the sheet, burns it, urinates on it, or feeds it to Mundo. Never underestimate the importance of arbitrary gestures.

33

“E,” Mundo says. “E, e, e, e, e.”

He’s on the floor of a library, in another house, dressed only in a mask that resembles the head of a mouse. Persuaded, he tries to eat a piece of cheese that Latour has placed next to him on the rug. The mask doesn’t have any openings.

Translated by George Henson