my love affair with jewelry book

History of a Love Affair

George Henson

Preface

My love affair with Elena Poniatowska began in 1986. I was a graduate student at Middlebury College’s Summer Spanish School. Elena had been invited (along with the poet José Emilio Pacheco and novelists Antonio Skármeta and Luisa Valenzuela) by Mexican novelist Gustavo Sainz, whose course on Latin American contemporary novel I was taking. Her novel Hasta no verte Jesús mío was required reading for the course. I became enamored with the novel’s protagonist Jesusa Palancares, an illiterate peasant woman who proclaimed on the first page, “This is my third time back on Earth, but I’ve never suffered as much as I have now. I was a queen in my last reincarnation.” Who, I wondered, was this writer with a Polish surname, who was writing about a soldadera—a woman who fought in the Mexican Revolution? In the ensuing years, I would read more and more of her books. In 2008, on the suggestion of a colleague, I emailed Elena in the hope that she would allow me to translate a single short story for a special issue of the literary journal Nimrod dedicated to Mexican writers. Eventually, I would translate not one, but all the stories that make up the collection Tlapalería (published as The Heart of the Artichoke, Alligator Press, 2012). Since then, our paths have crossed in the United States, and I have visited her in Mexico City, most recently in June of this year. Whether by a strange twist of fate or odd coincidence, Elena returned to Middlebury College in 2017 to receive an honorary doctorate, and I, a year later, came to teach translation at the Middlebury Institute in Monterey.

The Dossier

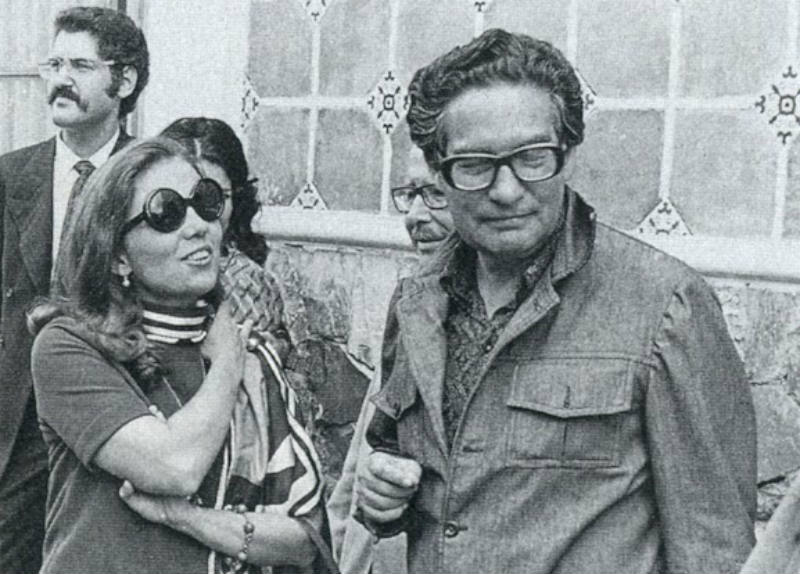

In this dossier, we offer an intimate glimpse into the life and work of one of Mexico’s most important 20th– and 21st-century writers, beloved by millions. In addition to an excerpt of the novel El tren pasa primero, both in the original and in my translation, you will find an essay titled “Elena Poniatowska: the Switchwoman of Memory,” written by Yuri Herrera, in which the Mexican novelist examines Elena’s role as guardian of Mexican historical memory in the novel that would earn Elena the prestigious Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize in 2007. In a review of Herrera’s debut novel Trabajos del reino (translated by Latin American Literature Today collaborator Lisa Dillman as Kingdom Cons), for La Jornada newspaper in 2004, Elena wrote, “With Trabajos del reino the young 34-year old writer Yuri Herrera enters the golden gate of Mexican literature.” You will also find a biographical sketch written by Elena’s authorized biographer and friend Michael Schuessler. In addition to these texts, we are honored to bring you a collection of photos—some seen here for the first time—that represent almost 80 years in Elena’s life, including candid photos of Elena with members of the Latin American Boom, as well as photos from my visit with Elena in June of this year.

June in Chimalistac

I arrive at Elena’s home promptly at 3 pm, not wanting a repeat of my visit last year when I arrived two hours late. Always the gracious hostess, Elena never mentioned the faux pas. Her home in a secluded cobblestoned enclave in Chimalistac, tucked behind a stucco wall that hides a lush jardín of flowers and trees, stands adjacent to the 16th-century church of San Sebastián Mártir, where La Malinche, Hernán Cortez’s interpreter, is believed to have been baptized. I ring the bell, and Martina, Elena’s longtime housekeeper, comes to the gate.

“Who is it?” she asks in Spanish through the wooden slats.

“It’s George, Martina.”

She opens the gate. “Elena’s out, but she’ll be here soon. Pase.” After many visits to Chimalistac, Martina’s fondness for me has grown, but her position requires that she still address me in the formal.

Martina is a diminutive woman who lords over Elena—herself on only 4’9’’—and whom Elena lovingly calls “the lady of the house.” Their affection for each other is genuine, enduring. While Martina uses the formal usted with me, she uses the informal tú, still reserved in Mexico for friends and family, with Elena. Martina is family.

She shows me in. I’ve brought a box of Godiva chocolates for Martina, an apology for having arrived late the time before. I sit in my usual chair, one of two yellow arm chairs that face the yellow sofa where Elena receives her guests. As always, there are fresh flowers. I’ve come for comida, Mexico’s main meal that falls between our lunch and dinner. Her son Felipe had arrived just seconds before. He’s come to discuss matters related to the Elena Poniatowska Foundation, which is in danger of being shuttered. I asked about the foundation and his mother’s health. “She’s well, especially for a woman of 87. I wish the foundation were doing as well.” Martina serves tequila and canapés. Elena arrives, harried and apologetic. This time it’s Elena who has arrived late. “Ay, querido Jorge, forgive me for keeping you waiting.”

“Elena Poniatowska Requires No Introduction”

Thus begins Michael Schuessler’s essay, “Elena Poniatowska: Talent and Personality,” which forms part of our dossier dedicated to the woman who, in addition to Mexico’s most celebrated living writer, is arguably her adopted country’s most beloved public figure. As Stephen Kurtz notes, however, in the Paris Review, while Elena’s “name is a byword throughout the Spanish-speaking world, […] English-language readers know her only from the small percentage of her work that has been translated.” Indeed, unlike many of her contemporaries, which include, among others, Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Carlos Fuentes, Elena’s vast and disparate oeuvre—over 40 books across a myriad of genres—has largely been ignored by American translators and publishers, among whose catalogues translated books represent a paltry three percent.

Who, then, is this writer who is largely unknown outside university Spanish departments in the United States while, in her native Mexico, as Chicana author Sandra Cisneros writes, “is as familiar to Mexican cab drivers as she is to Mexican professors”?

Miss Jujú

Elena Poniatowska Amor was born the Princess Hélène Elizabeth Louise Amelie Paula Dolores Poniatowska Amor, in Paris, on May 12, 1932, in a palace belonging to her maternal grandparents, Mexican aristocrats who immigrated to Paris in the mid-19th century. Her father was a Polish-American nobleman, the son of a collateral descendent of Stanisław August Poniatowski, the last king of Poland, and an American heiress. Following the Nazi occupation of Paris, Elena, her mother Doña Paulette, and her younger sister Kitzia fled to a country estate in the zone libre, before crossing the border into Francoist Spain, where the trio of Polish princesses boarded an ocean liner bound for Havana. Elena was 9. Upon arriving in Mexico in 1942, she spoke no Spanish, a language she would learn from her nana, an 18-year-old peasant girl named Magdalena Castillo. “The girls at my British school, who were from the best families in Mexico City, would tease me and say that I spoke Spanish like an india. I learned Spanish from street vendors and servants, but mostly from my Nana, who called me Miss Jujú.” Of Elena’s Spanish, the late Mexican poet and Nobel laureate Octavio Paz would write:

The language of Elena Poniatowska surprises me. It is not a purely colloquial language. Colloquialism for the sake of colloquialism is a literary mistake. But when the writer is able to transform daily language into literature, then a certain kind of musicality is achieved, which that winged, true, poetic thing that we see in the language of Elena Poniatowska has. […] If one is in the park when there are people strolling, children playing, workers walking, lovers kissing, gendarmes patrolling, vendors of this and that, lovers, nannies, mothers, and old women knitting, idlers reading a newspaper of a book, and birds. Well, Elena is that: a songbird of Mexican literature.

Elena’s colloquial language, learned in the streets and servants’ quarters, would become the trademark of her journalistic and literary oeuvre, which, in turn, is deeply rooted in the disparate and often convergent lives of the Mexican people. Seventy years later, Miss Jujú would win the prestigious Miguel de Cervantes Prize, the Spanish language’s most coveted literary award, for what the jury described as “a brilliant literary trajectory in diverse genres, particularly in narrative and an exemplary devotion to journalism.”

“Alice in the Land of Testimonials”

In the preface to Schuessler’s biography, Carlos Fuentes reminisces about meeting “La Poni”— like “Elenita,” one of Elena’s many nicknames:

I first met Elena at a ball held at Mexico City’s Jockey Club. She was disguised as a charming kitty cat, all in white; a true blonde, she wore a mask that covered only the top part of her face, and very lightly-colored jewels. She looked like some lovely and adorable creature dreamed up by Jean Cocteau. […]. We made our literary debut at the same time, many years ago, I with a volume of stories, Masked Days, and Elena with a singular exercise in childish innocence Lilus Kikus. The irony, the perversity of her first text was not immediately understood. Like one of Balthus’ little girls, like a Shirley Temple without dimples, Elena finally revealed herself as an Alice in Testimonial Land.

In July of this year, on the 50th anniversary of Hasta no verte Jesús mío (translated as Here’s to You, Jesusa!) in an interview with the Excélsior newspaper Elena recalls Josefina Bórquez, the woman who would become the protagonist of the groundbreaking testimonial novel to which Fuentes refers: “Everything she said was so extraordinary. The way she constructed her sentences was out of the ordinary. She used a lot of idioms, some she invented herself. She was coarse, but it didn’t matter. She spoke with such character and strength. She was a great seductress,” adding, “I miss her very much, and I even invoke her. When I’m afraid, I pray to two people: my mother and her. I ask them to help me. I invoke her as a guardian angel, as a protector, a guide.”

After Jesusa, came another defining book, both for Elena and for Mexican letters. La noche de Tlatelolco (translated as Massacre in Mexico) is a collage of testimonies, taken from survivors, witnesses, and family members, which Elena collected following the 1968 massacre of civilians, mostly university students, in Tlatelolco, a historical site in Mexico City that houses the Plaza de Tres Culturas. A then 36-year-old Elena, who was breastfeeding her youngest son, Felipe at the time went to the site between feedings and began to interview survivors and witnesses. La noche de Tlatelolco would earn Elena Mexico’s most important literary award, the Xavier Villaurrutia Prize, which she would publicly reject in an open letter published in the Excélsior newspaper to then President Luis Echeverría, who was responsible for the slaughter, saying, “Who is going to give an award to the dead?” Following her very public denunciation, Echeverría would have Elena surveilled. “The agents would park outside my house all day and all night. One day I decided to go outside and invite them in for coffee. But when I approached the car, they rolled up the windows and wouldn’t talk to me,” she told me. It was this kind of courage, which she has repeated hundreds of times in her newspapers columns, on television, and in public protests, at risk to her own personal safety, that has led many, like Carlos Tortolero, the founder and director of the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, to say of Elena, “she’s the conscience of Mexico.”

Saying Goodbye

Saying Goodbye

At 87, Elena has outlived most of the writers of her generation and many of those who, like Gustavo Sainz, who introduced me to Elena, belonged to the subsequent generation of Mexican writers. In an interview last year, Elena told the interviewer that she is now in her etapa de adiós—her “period of farewell.” Still, she shows no signs of slowing down. “I promised each of my grandchildren that I would dedicate a book to them,” she told me. She has 10. I ask her how the book she is writing now—a historical novel about the Poniatowski, the Polish noble family from whom she is descended—is going. “The editors want it yesterday. It’s been hard. I don’t read Polish, even though I am Polish, so I’ve had to do all my research in French. But I’m almost finished.”

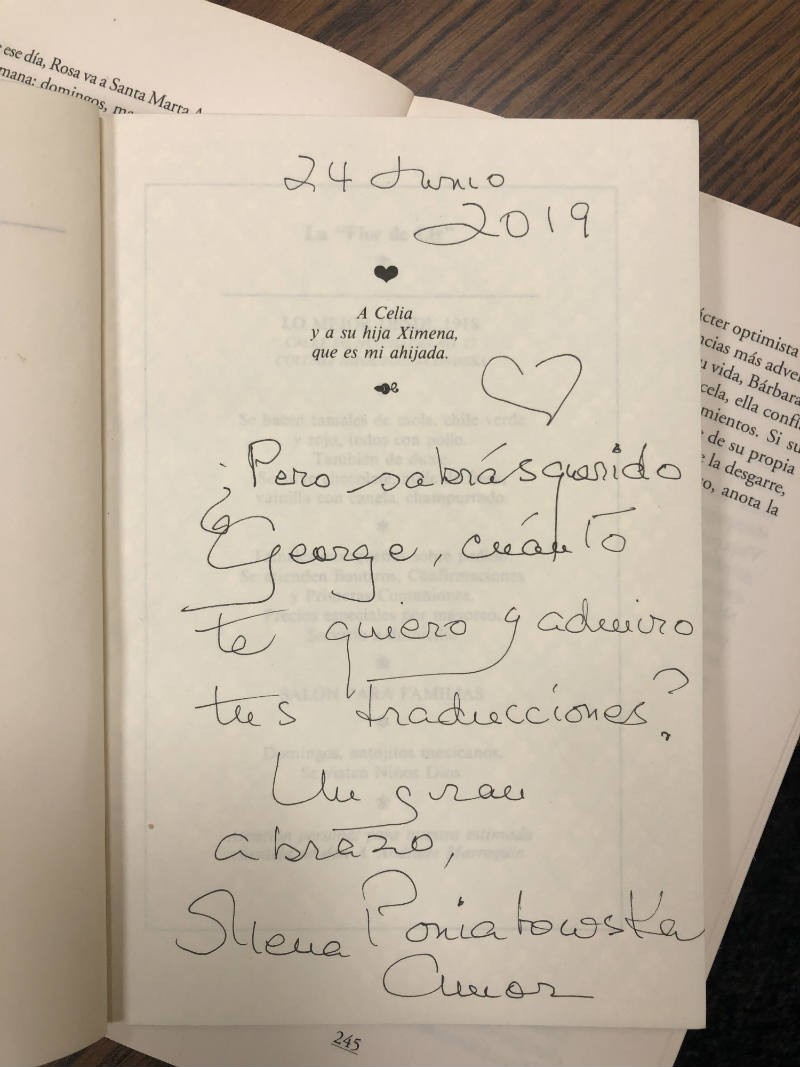

Before I leave her house at Chimalistac, I ask Elena to sign a stack of books I had bought that day. “Of course.” I hand her the books. One by one, she opens to the title page and begins to sign, first the date, 29 junio 2019, pausing to think. Each dedication is unique. As she writes, we continue to talk:

“Which book would you like me to translate next, Elena?”

“All of them.”

“But if I could translate just one.”

“The one I’m finishing now.”

In my copy of the still untranslated novel La “Flor de Lis” (The “Fleur de Lis”), Elena writes. “Do you know dear George how much I love you and admire your translations?”

I do, Elena. And I hope you know just how much I love you.

George Henson

Monterey, CA