Most of the Latin American and Latina women1 creators included in recent, global databases of electronic literature2 fall into the loose definition of e-poets. One of the earliest to make their mark in this emerging field was Ana Maria Uribe (Argentina), who worked in the field of visual and kinetic poetry. Over time she moved from creating non-digital “tipoemas” focusing on typescript and layout in the 1960s, to digitally remediated versions of the same, as well as the creation of “anipoemas” or digitally animated poems, from the 1990s onwards. In “Deseo – Desejo – Desire – 3 anipoemas eróticos” (2002), for example, the letters of each word perform a kind of dance, with musical accompaniment, to illustrate the word’s meaning.

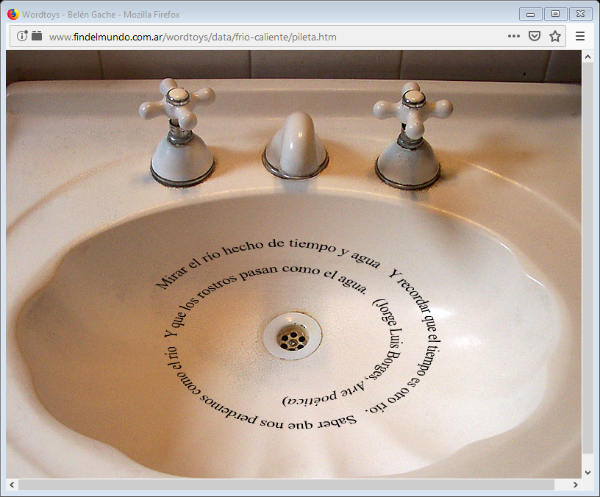

Other key figures with long careers in the field of e-poetry are Belén Gache (Argentina) and Giselle Beiguelman (Brazil). Gache is a prolific creator who started producing works of “expanded and experimental literature” – interactive works, video poems and multimedia narratives – for circulation and consumption online from the mid-1990s via the Fin del Mundo website (1999-2009). In terms of her contribution to e-poetry per se, Gache is perhaps best known for her highly intertextual approach, as well as her pushing at the boundaries of new media, as is evident in the hypermedia works Wordtoys (2006) and Góngora Wordtoys (Soledades) (2011). Wordtoys takes the form of a digital remediation of a traditional book, with titles and illustrations and pages that “turn” when clicked. When links embedded in the pages are clicked, they bring up pop-up screens that, in visually engaging ways, offer readers the chance to explore a selection of quotes on a given theme (butterflies or water, for example), or to interact with the material by trying (and failing) to write their own version of The Quixote. In Góngora Wordtoys each poem is a deliberate remixing or “mash-up” of Góngora’s Soledades (1613) that does not seek to reveal the meaning of Góngora’s works, but to explore how the principles that underpin his pushing at the limits of traditional poetry on a printed page can transfer to the new media poet’s experimental toolkit.

Beiguelman is perhaps more comfortably considered a “media artist” than a writer, but she defines some of her earliest work – for example, Leste o Leste? [Did You Read the East?] (2002) and Poétrica (2003) – as being or containing an element of “nomadic poetry” (Beiguelman, 2007), and some of her subsequent work dialogues specifically with the languages of computer coding (for example, //**Code_UP [2004]), and with the use of QR codes (The QR Poem [2010]). Most notable about Beiguelman’s work is her extensive experimentation with the movement back and forth – hence “nomadic” – between different platforms/screens and between different languages – phonic, human languages, non-phonic scripts and programming languages. In Poétrica, members of the public could submit text messages to be converted into a symbolic script defined by Beiguelman, before being exhibited on three electronic billboards in central São Paulo that the artist had taken over for the duration of the project. Subsequently, all original messages and their symbolic versions were curated on the project website, thus “revealing in some ways a community of poetic hackers of the telecommunication system who acts [sic.] in public spaces” (Beiguelman, qtd in entry on Poétrica on ELMCIP database). In The QR Poem, working in the opposite direction, the viewer-reader scans the QR code to reveal a text that simply states “at the intersections of words and symbols we begin to redefine our boundaries”. Overall, Beiguelman’s work seeks to frustrate our need to understand, to “get to the bottom of things”, and to reveal the limits of our reliance on human languages.

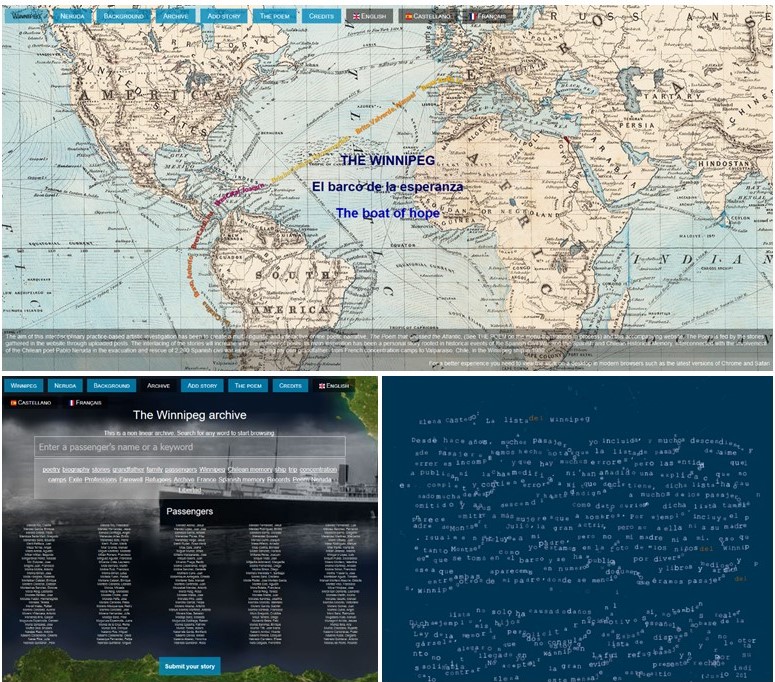

One other long-standing creator who deserves a mention is María Mencía. Born in Venezuela, Mencía was brought up in Spain and now lives and works in the UK. Nonetheless, she has been exhibiting her work in Latin America since 2002 and, in the context of the celebration of the first E-Poetry Festival to be held in Latin America (Buenos Aires, 2015), she turned to her Latin American roots for inspiration. El poema que cruzó el Atlántico [The Poem that Crossed the Atlantic] (2017) is a response to her family’s history of exile in Latin America as a result of the Spanish Civil War (1937-39). As Mencía notes on the opening screen of the work, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda organised “the evacuation and rescue of 2,200 Spanish civil war exiles – including [her] own grandfather – from French concentration camps to Valparaiso, Chile, in the Winnipeg ship in 1939”. In response Mencía has created a website documenting the context for the voyage of the Winnipeg, a user-generated archive for others involved to add their own memories, and a “poem” that offers the viewer/reader a way to access those archived memories in an aleatory manner by clicking on random letters that seem to float against a murky grey-blue “sea”.

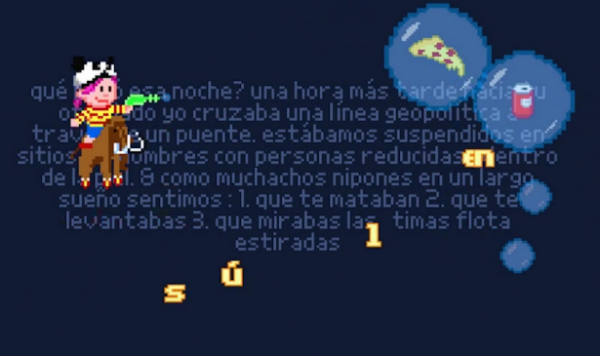

E-literature has “nodes” of feverish activity in certain Latin American countries, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Chile being the most obvious. In recent years there has been a particularly vibrant node of e-poetic activity in Mexico: some creators who deserve a particular mention include Minerva Reynosa, Laura Balboa and Karen Villeda, as well as sound/performance poet Mónica Nepote, whose work alongside video-artist Grace Quintanilla at the Centro de Cultura Digital in Chapultepec is of great significance in developing Mexico, and Mexico City specifically, as a key centre for the creation and dissemination of electronic literature and art.3 Balboa’s playful collection of “code poetry”, you CODE me (2009), also written “you C O D E me”, is available online as a PDF to print out or, in a different variant, as a Flash book. In a similar vein to Beiguelman’s work, it attempts to reinscribe human communication and interactions in the semantics of code by writing non-executable HTML code that humans therefore have to decode for themselves. She also moves between Spanish and English in the work, thus challenging the centrality of English as the language that interfaces most directly with computer code (Ledesma, 2015: 94-95). Villeda is best known for the project POETuitéame [POETweet Me] (2014), co-created with Denise Audirac, which offers the reader the chance to participate in a generative poetry experiment based on recent activity on Twitter. She has also created other works of hypermedia poetry in a similar vein to Gache’s intertextual e-poetic work: see, for example, Sorjuanízate [Sorjuanise Yourself] (2016). Reynosa has worked together with e-poet partner Benjamín Moreno to produce Mammut [Mammouth] (2015), a collection of “concretoons” – a neologism bringing together concrete poetry and cartoons, where the poem is delivered as part of a retro-style video game.

Poetry of one form or another has been a major feature of electronic literature, perhaps because, being generally a short, condensed experience, it fits better with the spatio-temporal parameters of screen-mediated lives. Nonetheless, there are several instances of narrative e-literature projects created entirely or lead by Latin American and Latina women. Some of the very earliest works, though notably quite technically-advanced for their moment of composition, are the autobiographical hypermedia projects Sangre Boliviana [Bolivian Blood] (1994) by Latina artist Lucia Grossberger Morales (Bolivia), and Glasshouses: A Tour of American Assimilation from a Mexican-American Perspective (1997) by Chicana artist Jacalyn Lopez Garcia (USA). Gache is, of course, another early point of reference in the field: one of her first works was El diario del niño burbuja [Bubbleboy’s Diary] (2001), an “Oulipean” hypermedia work composed of 100 short texts (based on random images found online) written over 100 days, without plot or specific theme. Other early works include Desde aquí [From Here] (2001) by Mónica Montes (Colombia), a very simple hypermedia work (text and images only) telling the interrelated stories of three characters, and El alebrije4 (2004) by Carmen Gil Vrolijk (Colombia) and Camilo Giraldo Ángel (Cuba), a more complex hypermedia collection of “crónicas de viaje, diarios y seres del caos” [travel accounts, diary entries and chaotic beings] structured around a young photographer’s discovery of a travel diary that leads her to an exploration of the more “fantastic” side of contemporary Mexico.

Many works of electronic literature by Latina and Latin American women have been avowedly collaborative projects. In much recent work this undoubtedly has to do with the increasing technical complexity of the projects and the limitations of any one individual’s skillset, but also, in the case of many of the works reviewed here, group work, collaboration with specific existing communities, and/or the creation of new affective communities around a work, is very much part of the point. This impetus was apparent in Lopez Garcia’s Glasshouses project where, already in the mid-1990s, she used a comment function to gather together those people (predominantly Latinas) who had similar personal experiences of hyphenated cultural identity to share. In Milagros sueltos [Sundry Miracles] (2007-2008), seven Costa Rican writers (four women and three men)5 came together to work on a text-only collective novel writing project where seven different characters interweave stories relating to a particular 2 August, the day of Our Lady of the Angels, patron of Costa Rica. Reader comments on the site suggest a largely positive initial response to the collective (and specifically Costa Rican) nature of the project. Umbrales [Thresholds] (2016), a recent hypermedia work by Yolanda de la Torre (Mexico), Raquel Gómez (Mexico) and Mónica Nepote, is not just a collaboration between the three women listed above, but also the result of de la Torre’s long-standing work running literary workshops with psychiatric patients to explore the therapeutic possibilities of writing: the texts that comprise Umbrales were written by the patients themselves. The work has the possibility, therefore, to form part of the therapy, offering a platform for shared experience and the development of an affective community of patients and readers. Although two of the sections of the work allow readers to draw, write or rearrange existing texts, there is no way of identifying authors of these “comments” to examine who is reading the work and, importantly, to know whether the patients themselves are reading it and forming a community around their own writings.6 The patients remain, therefore, somewhat “on the threshold” of full participation in the work.

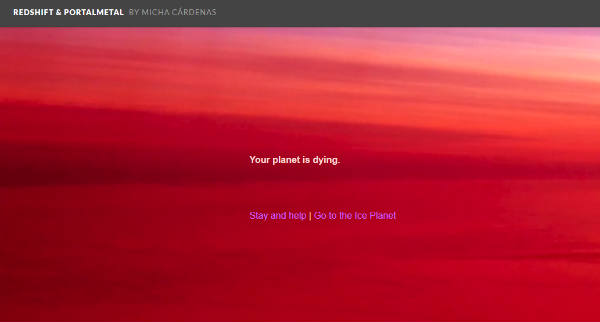

The liminality of Umbrales’s psychiatric patients contrasts with encouragement of reader identification with the transsexual, refugee protagonist of Redshift and Portalmetal (2014), by Micha Cárdenas (USA). This work is a science-fiction hypermedia game, including film, poetry and performance, about environmental catastrophe on earth and possibilities elsewhere in the solar system, that is narrated from the point of view of Roja, a trans Latina woman. The game raises questions about how to build new, inclusive societies without going down the route of colonisations past. Furthermore, referencing specific extant communities as its source of inspiration, beyond the obvious embrace of the trans community, in the credits Cárdenas states that this environmentalist work is made “in honour of the struggles of the native peoples of the Anishinaabe, Mississauga, New Credit and Grassy Narrows territories, where environmental destruction is a huge ongoing threat”. Cárdenas’s current collaborative AR game project, Sin Sol / No Sun (2018–) is a logical extension of the concerns raised in Redshift and Portalmetal, where a trans Latina AI hologram called Aura encourages players to “deeply consider how climate change disproportionately effects [sic.] immigrants, trans people and disabled people” (Cárdenas, Sin Sol).

Fig. 8. Micha Cárdenas, Redshift and Portalmetal (2014), screengrab.

The desire to create communities is also a defining feature of many blogs written by women. While blogging is not typically included in definitions of e-literature,7 it is here that Latin American and Latina women writers can be seen to have their biggest impact in terms of garnering, and occasionally mobilising, an audience. Blogging has really flourished in Cuba, despite restrictions on internet access. At the peak of its success in 2008-09, and after being blocked by Cuban government censors, the blog Generación Y (2007–),8 written by Yoani Sánchez (Cuba), was receiving an average of 10 million visits and 30,000 comments a month), and was being crowd-translated into multiple other languages (Henken, 2010: 217-18). While some of Sánchez’s work has a feminist focus, her main aim is to vent her frustration with the state of contemporary politics in Cuba, and propose a “revolution” of her own, powered by digital technologies.

In contrast, in Negra cubana tenía que ser [It Had to Be a Black Cuban Woman] (2006–), by Sandra Álvarez Ramírez (Cuba), the author takes a less Manichean approach to politics in Cuba and focuses instead on the intersectionality of the Black, female, queer experience. Although the impact of Álvarez Ramírez’s blog is far less than that of Sánchez’s – she has c. 6,500 regular followers – according to Sierra-Rivera, Negra cubana is most “revolutionary” for its attempt to network “a cyberfeminist agenda to connect Cuban black women’s voices with other voices around the world” and “create safe online networks where women can openly discuss any issue without being threatened” (Sierra-Rivera, 2018: 330; 339). While not all the women writers and artists mentioned above specifically engage a feminist, let alone a cyberfeminist agenda, this creation of “counterpublics” by writers such as Álvarez Ramírez is an important facet of Latin American women’s writing online (cf. Friedman, 2017).

Electronic literature by Latina and Latin American women creators is, as I hope is evident from this overview, an exciting, innovative, diverse and dynamic field of cultural production. While some attention has recently been paid to women creators of electronic literature (cf. María Mencía’s edited anthology #WomenTechLit [2017]), there is still no significant research available that targets the contributions of Latin American and Latina creators specifically. This overview is intended, therefore, to be a first step in this direction, and an invitation to others to fill this gap.

Notes

1 I use “woman” and “female” in this piece to refer to anyone who identifies as such, regardless of biological sex.

2 Cf. the Electronic Literature Organization’s Collections 1-3 (2006-2016) and the Electronic Literature as a Model of Creativity and Innovation in Practice (ELMCIP) “knowledge base” (2013–).

3 Nepote is the director of the Centre’s “E-literatura” project, which has curated a collection of works including Xitlálitl Rodríguez, Raquel Gómez and Julie Boschat’s Catnip (2015), Yolanda de la Torre, Raquel Gómez and Mónica Nepote’s Umbrales (2015), as well as the Antología de Poesía Electrónica (2018) including: Romina Cazón (Argentina), La poesía es una diosa; Nadia Cortés (Mexico), Filiaciones textuales; and Ana Medina (Mexico) Seis minutos para tomar el T.

4 ‘Alebrijes’ are Mexican handicrafts consisting of colourful papier-mâché models of imaginary creatures.

5 The writers were Dorelia Barahona, Pedro Pablo Viñuales, Floria Bertsch, Janina Bonilla, Víctor Valdelomar, Catalina Murillo, and Jaime Ordóñez.

6 The website also gives no information on the process of gaining informed consent from patients.

7 The tendency is to accept “blog-novels” such as Hembros: asedios de lo post humano (2006–) by Eugenia Prado Bassi (Chile), but not non-fiction blogs. The reticence to accept non-fiction blogs as e-literature may be because they are seen as being too easily “printed out” so not “electronic” enough (although this is disputable these days), or because they are not “literary” enough (though blogging fits very well with that sui generis Latin American literary genre, the chronicle).

8 The blog was originally hosted on Desde Cuba, moving to 14ymedio in 2014.

Bibliography

Beiguelman, Giselle. 2007. “Nomadic Poems”, in Eduardo Kac, ed., Media Poetry: An International Anthology (Bristol: Intellect), pp. 97-103.

Friedman, Elisabeth Jay. 2017. Interpreting the Internet: Feminist and Queer Counterpublics in Latin America (Oakland: University of California Press).

Henken, Ted. 2010. “En busca de la ‘Generación Y’: Yoani Sánchez, la blogosfera emergente y el periodismo ciudadano de la Cuba de hoy”, in Buena Vista Social Blog: Internet, y libertad de expresión en Cuba, ed. Beatriz Calvo Peña (Valencia: Advana Vieja), pp. 201-42.

Mencía, María, ed. 2017. #WomenTechLit (Morgantown, WV; Rochester, NY: Computing Literature).