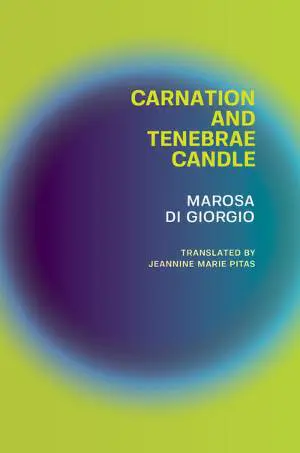

Clavel y tenebrario/Carnation and Tenebrae Candle. Marosa Di Giorgio. Translated by Jeannine Marie Pitas. Phoenix: Cardboard House Press. 2020. 126 pages.

The presence of Marosa Di Giorgio (Salto, 1932–Montevideo, 2004) in the poetic scene of Uruguay’s Generation of 60, also called the crisis generation, is an atypical one. Marked by the Cuban Revolution and the economic, social, and political crisis that unfolded in Uruguay starting in 1955, the majority of the poets that were this author’s compatriots and contemporaries cultivated a poetry of social themes, generally in free verse, although without rejecting fixed meter forms (as in the case of Washington Benavides, who composed song lyrics in order to express protests and proposals during the crisis, in a way that would be understandable to the average reader).

The presence of Marosa Di Giorgio (Salto, 1932–Montevideo, 2004) in the poetic scene of Uruguay’s Generation of 60, also called the crisis generation, is an atypical one. Marked by the Cuban Revolution and the economic, social, and political crisis that unfolded in Uruguay starting in 1955, the majority of the poets that were this author’s compatriots and contemporaries cultivated a poetry of social themes, generally in free verse, although without rejecting fixed meter forms (as in the case of Washington Benavides, who composed song lyrics in order to express protests and proposals during the crisis, in a way that would be understandable to the average reader).

Following different thematic and stylistic paths, Di Giorgio cultivated a less communicative poetry, without direct allusions to the political situation, styled as poetic prose, with free-verse interpolations, rich in symbolic allusions to the erotic, with the constant presence of the plants and animals of the Salto farm where she spent her childhood, but transformed by the poet’s boundless imagination, something that couples her work to that of Lewis Carroll, but with a darker and more disquieting tone. As with other Latin American poets raised in pre-Vatican II Catholicism, there is a recurring presence of Catholic imagery in her poetry, used in a peculiar way, against the canonical grain. In this regard, as well as that of the strong presence of the erotic, Marosa was a continuation, as she herself acknowledged, of Delmira Agustini (Montevideo, 1886–1913), poetic great of the Generation of 900.

A poet with a cult following in her lifetime, the popularity of her work after her death has grown continuously. This is evidenced by the large number of English translations and bilingual editions the translator mentions in her brief, clear, and instructive afterword. It should also be noted that the translator is effective at the difficult key tasks posed by the original: recreating the atmospheres, the images, and the halting rhythm that Di Giorgio instills in her prose, by way of her atypical usage of punctuation. The translation decisions, above all those of the names of animals or plants, are apt. For example: Pitas uses lion’s tooth to translate “diente de león,” instead of dandelion, in order to preserve the animal allusion implicit in the Spanish name of the plant, which is retained only etymologically in the English word (dens leonis in Latin, dent-de-lion in French, and finally, dandelion in English).

When Di Giorgio published Clavel y tenebrario, her ninth book, in 1979, she had reached maturity in both life and creativity, while Uruguay, just like the entire Southern Cone of Latin America, was suffering a dictatorship that condemned her generational companions to jail, to exile, to silence, or to the arduous adoption of a language written between the lines. The texts of this poet from Salta, published by Editorial Arca from 1971 on, would earn not a massive audience but a qualified and faithful one, on both sides of the Río de la Plata. Her poetry readings would also win her followers. In Argentina, starting in the nineties at the hands of publishers such as Adriana Hidalgo and El Cuenco de Plata, Di Giorgio’s audience would steadily and continuously grow.

Beginning with the title, this book unites the natural and the religious: the Tenebrae candle is a triangular candelabra of fifteen tiered candles that are extinguished one by one to leave only the candle at the apex lit, as a symbol of Christ, in the Tenebrae service during Holy Week. The image is key to interpreting this book and all of Di Giorgio’s work; light and tenebrosity are inseparable and each emphasizes the other. Thus, for example, figures of the feminine, particularly the figure of the mother, can bring together the tender and the terrible, reason and madness. And thus, the childhood and adolescence evoked by these texts, as well as the magical place in which they took place, the small family farm, are at once happy and sorrowful, and have room for not only visitors and games but for a plague of locusts, as well.

The transition from the innocent to the cruel, from the living to the ghostly, is at times very abrupt, so much so that it happens surprisingly, in the same brief fragment. Take, for example: “Walking to school, sweetly; they opened all around, the / melodious farmlands, the broad beans, the cry of the birds, the / squashes roasting themselves in their own yellow tulle. / There was no one; some dead man passed by flying…” (Fragment 9; emphasis mine; all textual quotations are translated by Jeannine Marie Pitas).

In the magical terrain, past and lost, that these texts evoke, tragedy and death are always nearby, and they are remembered partly with guilt and partly with a certain levity, as though the lyrical speaker retained, in a mysterious way, mixed with guilt, much of her childhood innocence. Take this example: “The turkey hen was waddling through the blossoming broom plants, unaware that Christmas was coming. / She looked more like a young lady with blue feathers, a coral necklace, and an obsession with getting married. / I believe that she even laid some eggs, white as marble, or blue, or purple. I don’t know, since that was before. / And the crime was committed behind my back. / But maybe there is still something of her running through my veins. / It stays with me like a regret. / A strange memory” (Fragment 14).

It is interesting, this identification between the turkey hen that is to be sacrificed and the girl/young woman who observes her, especially in details such as the obsession with getting married. Shortly after alluding to nuptials, there is mention of sacrifice. The possibility of erotic union is, in this book and in Di Giorgio’s work in general, contemplated with simultaneous desire and fear. But in these poems, death is soon bested by birth. With a sage sense of balance, the author reveals, in the following fragment, that this house had a room in which the most varied things were born: “cutlery, graters, plates, pans, cups. Everything there, meticulous, tender, and nearly trembling.”

The femininity of the girl/young woman who is the subject of these texts is at once boundless and subtle, chaste and precocious. These texts address, in a poetic key, the age at which a woman determines, among other things, that she is embodied in two figures: Arturo, a young man with a star’s name, with whom the lyrical speaker falls in love at the age of three, and the father, who is both a sort of God, creator of the domestic universe, and the Christ who goes to the cross to save it.

All in all, this bilingual edition is a good doorway through which the English-speaking reader may enter an intense, suggestive, ghostly, and luminous work of poetry. Marosa Di Giorgio, one of the best Spanish-language poetic voices of the twentieth century, deserves to transcend the borders of her tongue.

Juan de Marsilio

Directorate General of Secondary Education, Uruguay

Translated by Audrey Meshulam