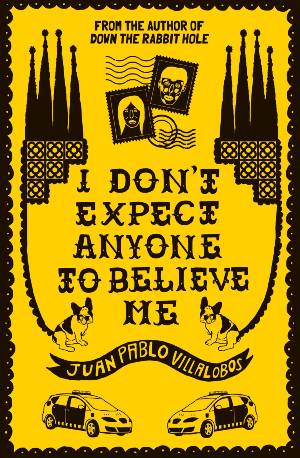

“I don’t expect anyone to believe me,” warns the narrator of this novel, a Mexican student called Juan Pablo Villalobos. He is about to fly to Barcelona on a scholarship when he’s kidnapped in a bookshop and whisked away by thugs to a basement. The gangsters are threatening his cousin―a wannabe entrepreneur known to some as “Projects” and to others as “dickhead”―who is gagged and tied to a chair. The thugs say Juan Pablo must work for them. His mission? To make Laia, the daughter of a corrupt politician, fall in love with him. He accepts. . . though not before the crime boss has forced him at gunpoint into a discussion on the limits of humour in literature. Part campus novel, part gangster thriller, I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me is Villalobos at his best. Exuberantly foul-mouthed and intellectually agile, this hugely entertaining novel finds the light side of difficult subjects―immigration, corruption, family loyalty and love―in a world where the difference between comedy and tragedy depends entirely on who’s telling the joke.

“I don’t expect anyone to believe me,” warns the narrator of this novel, a Mexican student called Juan Pablo Villalobos. He is about to fly to Barcelona on a scholarship when he’s kidnapped in a bookshop and whisked away by thugs to a basement. The gangsters are threatening his cousin―a wannabe entrepreneur known to some as “Projects” and to others as “dickhead”―who is gagged and tied to a chair. The thugs say Juan Pablo must work for them. His mission? To make Laia, the daughter of a corrupt politician, fall in love with him. He accepts. . . though not before the crime boss has forced him at gunpoint into a discussion on the limits of humour in literature. Part campus novel, part gangster thriller, I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me is Villalobos at his best. Exuberantly foul-mouthed and intellectually agile, this hugely entertaining novel finds the light side of difficult subjects―immigration, corruption, family loyalty and love―in a world where the difference between comedy and tragedy depends entirely on who’s telling the joke.

Available soon from And Other Stories.

My cousin calls me up and says: I want to introduce you to my business partners. We agree to meet at five-thirty on Saturday at the Plaza México shopping center, outside the multiplex. When I arrive, there are three of them there, plus my cousin. All with dark fuzz on their upper lips (we’re sixteen at this point, maybe seventeen), faces covered in spots oozing a viscous yellowish liquid, with four enormous noses (one apiece). They’re in high school with the Jesuits. We shake hands. They ask me where I’m from, just assuming I can’t be from Guadalajara, maybe because when we shook hands I kept my thumb pointed skyward. From Lagos, I say, I lived there till I was twelve. They don’t know where that is. In Los Altos, I explain, three hours’ drive away. My cousin says that’s where his father’s family is from, and that his father and my father are brothers. Ah, they say. We’re fair-haired people from up in Los Altos, my cousin explains – as if we were some subspecies of the Mexican breed: Blondus altensis – and his business partners exchange glances, each in turn, with a sarcastic little glint in their upper-middle-class Guadalajaran eyes, or possibly lower-upper-class eyes, or possibly even aristocracy- come-down-in-the-world eyes.

So what’s this business you guys are doing? I ask, before my cousin gets a chance to start detailing the genetic havoc wreaked by French soldiers during the Intervention, the nineteenth-century bastard origins of our eyes that are blue, and our hair that is blond, or at least light brown. A golf course, says my cousin. Over in Tenacatita, says one of the others. A piece of land that belongs to my friend’s brother’s father-in-law, says another. We’re having lunch with him next week at the Industrialists’ Club to present the project, says the one who hasn’t spoken yet. They explain that the only problem’s water, you need a huge amount of water to keep the greens green. But my cousin’s neighbor’s brother-in-law runs the public waterworks for the state, says another. That’ll get fixed with a quick backhander, says another. Everybody nods, pimples bobbing up and down, totally certain. All we need is a capitalist partner, says my cousin finally, we got to raise two million dollars. I ask them how much they’ve managed to get hold of so far. They say thirty-five thousand new pesos. I do the calculation in my head, and it comes to something like fifteen thousand dollars (this is all happening in 1989). Thirty-seven, another corrects him, I’ve just gotten hold of another two thousand from my sister’s friend’s sister. They exchange congratulatory hugs for the two thousand new pesos. So, are we going to a movie or not? I ask, because my cousin and I usually go to the six o’clock screening on Saturdays. We discuss what’s on the bill: there’s an action movie with Bruce Willis and another with Chuck Norris. The two-thousand-new-pesos guy says there’s nobody back at his place, his family’s gone to spend the weekend in Tapalpa and he knows where his dad hides his stash of porn movies. And his house is nearby. Just behind the square. In Monraz. Why don’t we check it out? Some pimples pop from the excitement, like purulent premature ejaculations.

Our host picks the movie. It’s called Hot Shrinks and Wild Kinks. We draw lots for our turn to masturbate (every man for himself, one at a time). My cousin gets to go first, and though there’s a limit of ten minutes per guy, he takes ages. While we wait for him, all excited, drinking Cokes, his business partners quiz me, as we sit together in the living room of a house decorated like a colonial ranch, totally fake, with these incredibly uncomfortable armchairs, because it apparently didn’t occur to anybody that the neo-Mexican style is no use unless you’re doing the set design for a telenovela. They ask me if we have cars in Lagos. If electricity and telephones have made it there yet. If we brush our teeth. If my father carried my mother off on a horse. I answer yes, yes, of course. And where did you leave your big sombrero? they ask. I forgot it in your sister’s bedroom, I say to the one who asked, who as it happens is the host, the one whose parents think if you paint a ranch house in a wash of bright colors it’s going to look a picture of elegance. My sister’s six years old, he says, suddenly angry, and he gets up to hit me. I’m kind of amazed that the sister of a friend of his sister’s, who is six years old, is in a position to invest two thousand new pesos in this proposed golf course. If her friend is a friend from school, in year one of primary, and she’s also six, how old can her sister be? Eight? Ten? And that’s assuming it’s her older sister. What if she’s her younger sister? But I don’t have time for financial speculation because the sister’s brother is up with all his pimples and his fists ready to lay into me. I leap to my feet, knocking a ceramic watermelon off a little side table – though, whatever people say about the fragility of Tlaquepaque handicrafts, it doesn’t actually break – and run across the front garden, out into the street, slam the gate behind me, cross over and run very fast down the median, really incredibly fast, just like the hero of one of those action movies we didn’t watch, except with a great ache in my testicles (I never got my turn to masturbate).

Fifteen years later, we’re in 2004 now, another call from my cousin: I want to introduce you to my business partners, he says again. I tell him I’m really busy, I’m going off to do my doctorate in Barcelona. I know, he says, your dad told me, that’s why I’m calling. I don’t see what one thing has to do with the other, I say. I’ll explain when I see you, he says. Honestly, I can’t, I insist, I’ve got this long list of errands that need doing, this is my only week in Guadalajara, I’ve got to go to Mexico City to process my visa and then back to Xalapa to finish packing and pick up Valentina. You owe it to me, he says, for old times’ sake. Anybody’s guess what he could be referring to. In the old days all we ever did was go to the movies at six o’clock on Saturdays. And those old times didn’t last even a year, exactly up to the afternoon I had to run away from the house of one of his business partners who wanted to lynch me. That same night, my cousin called to say my behavior was damaging his business prospects. I told him he could stick his project up his ass, though I used a paraphrase that didn’t involve the word ‘ass’. We stopped seeing each other. When I finished high school I went off to live in Xalapa, to study Spanish literature at the University of Veracruz. He went off to do International Business at the ITESO university, being a good follower of those Jesuits, but he never graduated. He went to live in the US for a bit, in some town near San Diego, where a sister of our fathers’ lives. He said he was going to do a postgrad, an MBA, that’s what he told my dad, ignoring the minor detail that in order to do this he’d need to have completed his degree. One of my aunt’s kids, one of the cousins who live in America, that is, told me our cousin had settled in their parents’ house, where he did nothing but watch TV, supposedly to learn English though he actually only watched Univision. Then he came back to Guadalajara and went over to Cabo San Lucas. According to my mom, my aunt told her he bought a small motorboat to take tourists out whale-watching. But he didn’t have a license and the union of whale guides made his life hell, until one day they sank his boat, which he’d kept docked at a secret jetty. He came back to Guadalajara. He set up a surfboard store in Chapalita, which never caught on, and he had to close it within a few months. He set up a stand selling Ensenada-style fish tacos on Avenida Patria, but within two weeks the health inspectors from the Zapopan district council had shut it down. They’re really out to get me, that’s what my dad said my cousin told him at my grandfather’s ninetieth birthday party, which I didn’t go to because I was in Xalapa. He says he’s been the victim of a bureaucratic plot. That it’s impossible to do business in Mexico. He left again, for Cozumel this time, where for years nobody really knew what he was up to. My uncle told my sister he was waiting tables in a little thatched palapa hut where they made pescado zarandeado, except that’s a Pacific-coast fish recipe, not a Caribbean one. My aunt told my mom he was taking care of some projects for a group of foreign investors. She couldn’t say what projects, or where the alleged foreign investors were from. Assuming they even existed, these alleged investors. One of the few times we were together again, at the wedding of another cousin, he shouted in my ear, amid the din of a small brass band (the bride’s family was from Sinaloa), that he was living off his rental income. I thought I’d misheard, not least because at that time we can’t have been older than twenty-seven or twenty-eight. You have property on the Caribbean? I asked him, with the utmost suspicion. Yeah, he said, ten sunbeds plus their shades. He had recently returned to Guadalajara, supposedly as a project manager for an investment fund. Someone in the family told me, I can’t remember who, that it was money from American retirees living in Chapala.

As for me, the only thing I’d done in all those years was complete my degree, write a thesis on the short stories of Jorge Ibargüengoitia, win a scholarship from the Institute of Literary-Linguistic Research and teach Spanish to the very occasional foreign students who showed up in Xalapa.

I swear you won’t regret it, says my cousin, bringing me out of the long silence that followed his demand for totally unearned loyalty, and of which I’d taken advantage to cast my mind back over the fifteen years that separated the old days from the new. I won’t take up more than half an hour of your time, he says, if you’re not interested you’ve only wasted half an hour, but I totally know you’re gonna be interested. Specially ’cause that scholarship you got isn’t going to get you very far. Your dad told me. Life in Europe’s seriously expensive.

And now, instead of describing how I eventually ended up agreeing to meet my cousin, instead of dwelling on the swiftness with which I came to the conclusion that this was the only way of getting him off my back, instead of acknowledging that I did go, voluntarily, on my own two feet, to throw myself off the precipice, I’d rather, as the bad poets say, draw a dark veil over this fragment of the story, or more precisely, choose this place and this moment to make use of an effective and moderately dignified ellipsis.

Translated by Daniel Hahn