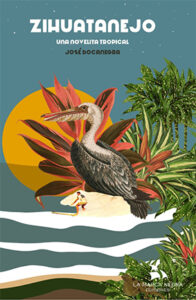

Murcia: La Marca Negra. 2022. 202 pages.

When it comes to the new novel by Mexican writer José Bocanegra, Zihuatanejo (La Marca Negra, 2022), we are talking about a narrative project that, along with Corralejo (2015) and Vacas (2020), is worth assessing as part of an ensemble. The three novels share similar plots. The protagonist abandons their daily life of routines and forced work to go on vacations that let them surf in a new and enticing environment, a carbon copy of a paradise lost; they meet a cast of characters, go through a series of experiences, and at the end of the road they return to the purgatory of daily life.

When it comes to the new novel by Mexican writer José Bocanegra, Zihuatanejo (La Marca Negra, 2022), we are talking about a narrative project that, along with Corralejo (2015) and Vacas (2020), is worth assessing as part of an ensemble. The three novels share similar plots. The protagonist abandons their daily life of routines and forced work to go on vacations that let them surf in a new and enticing environment, a carbon copy of a paradise lost; they meet a cast of characters, go through a series of experiences, and at the end of the road they return to the purgatory of daily life.

As for their storylines, Bocanegra’s novels are structured like “jailbreak” movies, but backwards. In these movies the characters lose their freedom at the beginning, and the entire story arc consists of discovering which steps to take to regain it. Whether or not they do regain it, these movies always have a naïve premise: they deem that freedom is possible and that, somehow, it is within our reach. Bocanegra’s novels are slightly more skeptical in this respect, or more realistic. They begin with the protagonist’s release, but their freedom is always conditional, has an expiration date, and expires by the end of each novel. The plot, as such, is structured like a Greek tragedy. The hero is condemned from the beginning to fulfill their fatum. But seeing as we are not in Ancient Greece, that fatum is not determined by the gods. Or it is determined by the gods of our time: the capitalist forces of production that invariably catch up to the character by the end of their adventures. Such an approach may seem pessimistic, but it conceals a discreet and possible idea of happiness; Camus’s idea, which suggested that we must imagine Sisyphus happy.

In Corralejo, Bocanegra puts forth that “Viajar es sólo el ensayo de una fuga” [“Travel is just rehearsal for an escape”]. And in his latest novel, a “jailbreak” movie triggers the plot. Zihuatanejo is the coastal town in Mexico to which the characters played by Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman flee at the end of The Shawshank Redemption, the film by Frank Darabont based on a short novel by Stephen King. And that is precisely what makes the protagonist of Bocanegra’s novel choose it as the destination where he will live out and recount his adventures and misadventures.

Bocanegra’s three novels are not only similar in terms of plot; they are also written using the same narrative technique. The author/narrator records the facts of life while on the go, in the moment of living them, and materializes them in the novel just as a painter takes notes from nature, in a work-in-progress exercise which, after passing through Bocanegra’s pen, ends up becoming a sort of “en busca del presente perdido” [“in search of the lost present”].

Up to this point we have covered the similarities between Bocanegra’s novels. Now, to speak of their differences, I would like to introduce the idea of distance. A novel can situate us too close to the narrative, or too far from it. When the author situates us too close to what is told, to the characters, to the ideas at stake, etc., the narrative is concretely lost; it inevitably falls apart into infinite details and becomes anecdotal. In that case, furthermore, the narration stays so close to the story it tells that it can usually offer us just one singular point of view. The anecdotal becomes dogmatic.

In contrast, a novel can situate itself too far from the narrative. The author widens their focus and takes on so much perspective that they may be able to offer us broad analyses and grand ideas, but easily become disconnected from the story and turn to abstraction. The narrative then becomes an excuse, puppet characters performing philosophical theater.

Corralejo is written with a fascinating rhythm and pulse. But it is written in the first person and the present tense; the protagonist is also the author and the narrator; he takes us by the hand, makes us live his experiences, share in his reflections and his judgment of reality. We may or may not agree with him, but we are always tied to his point of view. It is too close.

Vacas is an experimental novel and, as such, is paradoxical. It does not situate us too close or too far away. It makes a risky bet by inserting us directly into the thick of things. The whole novel is an internal monologue. But a monologue that is not limited to the internal workings of the protagonist. It is an internal monologue about reality. In Vacas, language finds its voice by penetrating into things themselves. The true experiment is the removal of all distance. Seeking that which Barthes called “writing degree zero.”

Lastly, in Zihuatanejo, we always walk hand-in-hand with the protagonist, as in the other novels, but here the author relativizes his protagonist; at times they agree, at others he sanctions him, laughs at him, pities him… The narration is no longer a reflection of his world but of a critical and ironic line of questioning. That type of questioning, of problematizing; that attempt to well and clearly discern that the novel is a good one. With Zihuatanejo, José Bocanegra has achieved the rare and difficult literary feat of situating us at the proper distance.