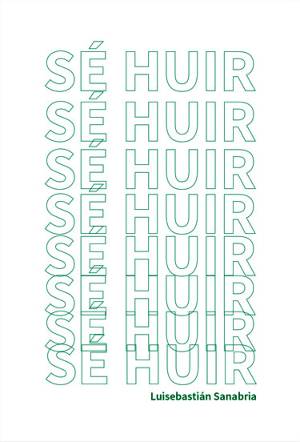

Sé huir. Luisebastián Sanabria. Bogotá: Dos Filos/Colección Material de Lucha. 2020.

Their masculinities didn’t know about caresses

Some of us do with literature what love does with the body. We undress the words searching for the language that is hidden, we turn it around, go through it, handle what we can and what we cannot. We, who do with literature what love does with the body, are not revolutionizing books but life, we undress existence with words. Sé huir is the undressing of one life, Luisebastián’s—that of the author, the narrator, the character; a versatile, softy, suburban queer.

Some of us do with literature what love does with the body. We undress the words searching for the language that is hidden, we turn it around, go through it, handle what we can and what we cannot. We, who do with literature what love does with the body, are not revolutionizing books but life, we undress existence with words. Sé huir is the undressing of one life, Luisebastián’s—that of the author, the narrator, the character; a versatile, softy, suburban queer.

Intimist literature is what this book displays, a literature that can be easily carried in a pocket, its minute size being disproportional compared with the magnitude of its confessions; anyhow, they say good perfumes come in small bottles. But its form and content do share something, something that is restricted, tight, almost suffocating from an existence that speaks of how a gay man’s life—like all diverse, non-hegemonic, and underprivileged lives—is a slow and painful countdown until the day when, at last, they decide to spread their wings.

To open this book in the middle is to see the author’s wings, physically—yes, to see that cliché image that has been published many times on book covers—but it does not matter if it is cliché; I know Luisebastián allows me to say this because he is a “hopeless romantic,” as he names himself, so things that are cliché are not wrong… So, one opens the book in the middle and finds a wound in the left wing: “Sebastián, about us, no one can know, it’s better that this stays between us. […] Not speaking of us both deterred me from verbalizing what I felt” (p. 40).

What a pain, isn’t it? When, for some reason, love is over this narrow world’s head.

But there it is, the right wing, vindicating the power of love: not someone else’s, but one’s own.

“The first victory over my body was with what I wore, through my clothes. […] My declaration was of an everyday nature, in the street, from one place to another. I thought it was important to make public my authority over my shapes—I walked with confidence, even if I hesitated, I walked with confidence.” (p. 41)

And that is how one goes, reading a man’s diary that in ten chapters—as if they were ten high steps—shows us the path that memory takes to reaffirm freedom. That race from one to ten is rapid, breakneck, and, above all, ravenous; it is like a photo album, with long-exposure images in which the protagonist is anyone who, to make their way, needs to flee. This book is many photos in motion, framed by the green edge of a book that has limits, that sets them; as if saying this is it, it’s a dead end.

As I was reading, I felt like timing the seconds I could hold my breath underwater, or the steps, the laps, the kilometers one runs; timing the minutes that go by when one has an anxiety attack or counting one’s heartbeats when one makes an important call and waits for the other end to answer. Because literature is, to a degree, like a phone call in which both ends speak at the same time and answer each other infinitely, it is just that sometimes they are not heard out loud.

Now I know that is why I needed to write about this book. To take inventory but also to count up the words with which I was left after reading Sé huir. Because it is necessary to write in order to take out from inside that beautiful and powerful thing that others mention to us; that thing that one has the duty to tell the whole world.

Reading is where silence gives names. It names the character, who is also the author and is also all my gay friends and all the gay men in the world, in all their shapes and numerous meanings, including that one, the one I like the most, the one that comes from Old French and says that gai means “being happy.” Ten chapters from a nostalgic man, a cry-baby queer—beautiful! One that takes from his sad memories a piece of joy as a manifestation of his resilience.

On the back cover, it says the road from one to ten is an appendix, “they are narrative fragments that talk about the growth of a strange feeling, pierced by silence, self-defense, and hideouts.” And that road, that journey, to the core that Luisebastián Sanabria talks about, names so many things! One, it names deconstruction, infancy, and childhood: “it came from ‘to write like a girl’: from an imaginary that has a clear distinction between feminine and masculine handwriting.” Two, it names rejection: “my mother explained to me why she can’t think of me as a fag. […] His son is ‘something’—in a way—that she doesn’t know how to name.” Three, it names adolescence, a period in which, beyond being painful, life becomes strange to us: “One night, someone proposed to play truth or dare. […] The dare was to dance […] no one was left without any doubt about my peculiar nature, now they knew I was not lying; that my waist, like me, was indecent.” Four, it names freedom, which gives us air but also shows us the cruelty of the world: “I moved to the apartment of one of my cousin’s female colleagues […] One night, she invited one of her friends to our house […], she took my clothes out of the wardrobe […] The chain of interpretations and mockery beat me up […] Now it finally happened: I could see her true colors.” Five, it names being queer, outrageous, a cacorro: “when I talked about my love stories, more than one person couldn’t help but chuckle. […] I had a gut feeling of my emotions being different, but I didn’t know where that difference was.”

I can follow with six, seven, eight, but I am starting to lose my breath, I think again about the seconds I can hold my breath underwater, and they are few, I confess, and I would need a lot, many more to express all the reflections this book grants me—on heterosexuality, politics, the paternal figure, abuse, violence, the vagueness of normality. I prefer to breathe and recognize from this experience, which seems distant—because I am a woman and I am bisexual—the thing, which thanks to words, brings us closer.

Books leave us with clefts too, like teeth do when someone bites us, and they help us recognize the anatomy where wounds match up. And, at the same time, they are testimonies, confessions, letters, diaries, stories of our own from other contexts that, from afar, seem like someone else’s stories, or stories from others that reach so deeply that they seem like personal revolutions. And how necessary empathy is, in this world that has so many fights left to start and does not know, sometimes, how to begin its battles.

How different would have been the lives of many, of her, of him, of them, of everyone, if a lodestar like this one would have existed decades ago; we would have felt less alone! But it arrived, not too late, not too soon, but right on time, like everything that is good, to blow some air behind those wings that are still afraid of flying.

I stop. I breathe. Yes, this is all I was talking about when I said what I said about doing with literature what love does with the body, “to dress the words to take away the other’s power” (p. 82); about the need to find a different way of saying the same thing; to write in the same way, such that it might be read differently.

Ivonne Alonso-Mondragón

Translated by Luisa María Jiménez