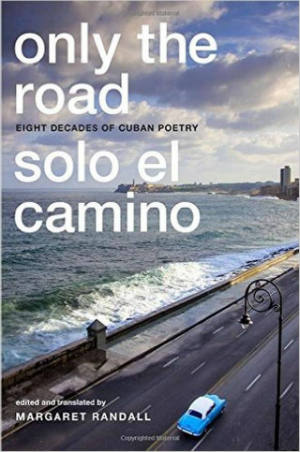

Only the Road / Solo el camino: Eight Decades of Cuban Poetry. Edited and translated by Margaret Randall. Durham: Duke University Press. 2016.

The Many Paths of Cuban Poetry: A Review of Margaret Randall’s Only the Road/Solo el camino

Cuban poetry is a category, a cultural repository, and a trope all of its own. To anthologize the various and diverse Cuban voices that have chiseled out verses on the sociocultural imaginary for the last eight decades is a monumental task. It is a project that requires a deep, and at the same time, broad-ranging knowledge of historical, political, and cultural processes, as well as the general poetics of the ever evolving set of Cuban experiences. As translator and editor, Margaret Randall’s bilingual anthology, Only the Road/Solo el camino: Eight Decades of Cuban Poetry (Duke University Press, 2016) comprehensively tackles the undertaking and the end result is a solid pathway of poetic approaches to Cuba. The collection delights the reader and piques their curiosity about the crossroads that underlie concepts or experiences such as: nation, revolution, migration, exile, and what these terms have come to signify.

Cuban poetry is a category, a cultural repository, and a trope all of its own. To anthologize the various and diverse Cuban voices that have chiseled out verses on the sociocultural imaginary for the last eight decades is a monumental task. It is a project that requires a deep, and at the same time, broad-ranging knowledge of historical, political, and cultural processes, as well as the general poetics of the ever evolving set of Cuban experiences. As translator and editor, Margaret Randall’s bilingual anthology, Only the Road/Solo el camino: Eight Decades of Cuban Poetry (Duke University Press, 2016) comprehensively tackles the undertaking and the end result is a solid pathway of poetic approaches to Cuba. The collection delights the reader and piques their curiosity about the crossroads that underlie concepts or experiences such as: nation, revolution, migration, exile, and what these terms have come to signify.

As a translator and also as a poet, Randall carefully examines the challenges of her project in the book’s introduction. She establishes the aim as a balancing act: staying true to both form and content in the process of translating. Aware that her inclusive endeavor calls for the incorporation of different generations of poets and voices within those generations, she also provides a wider contextual vision. In the words of Randall, “I chose work I feel is representative of each poet but also of Cuba’s poetic history and culture, in periods preceding and following the Revolution, times both exhilarating and difficult” (1). Therefore, Only the Road/Solo el camino provides more than an encompassing compilation of Cuban poetry. Through the voices of Nicolás Guillén, José Lezama Lima, Cintio Vitier, Roberto Fernández Retamar, Georgina Herrera, Lourdes Casal, José Kozer, Nancy Morejón, Luis Lorente, Marylin Bobes, Sigredo Ariel, Caridad Atencio, among 44 other poets, this anthology represents an extensive study of sociocultural radiographs by Cubans, and/or toward the significations of being a revolutionary (politically and/or creatively), and/or in the name of exploring what is poetry at large. To account for the different points of articulation of the Cuban experience, each and every one of the poets is featured with a concise yet informative biography.

The collection opens with Nicolás Guillén and his contemporaries, thus marking as initiators for the chronology of the book the generation born during the first decade of the twentieth-century. With echoes of the César Vallejo-style vanguardismo, Guillén’s “Piedra de horno” ends with the verses: “Carbón ardiendo y piedra de horno/ en está [sic] tarde fría de lluvia y de silencio” (28), to which Randall does the honor of a measured translation: “Fiery coal and kiln stone/ on this cold afternoon of silence and rain” (29). The anthology aptly concludes with a poet born in the decade of 1980, Anisley Negrín Ruiz, whose poem “Palabra de Seguridad” allows for the same type of measured, sober, and straightforward style of translation that Randall sustains throughout the book. As Negrín Ruiz’s aforementioned poem claims: “No queda más remedio que decir la palabra./ Mas/ ninguna palabra es segura hoy en día” (498); translated as “There is no solution but to say the word./But/ no word is safe these days” (499). The matter of poetry is at the core of the anthology, from the “piedra de horno” to the word that may or may not be safe. And if there is a word that shifts in certainty, that is: nación.

Israel Domínguez, born in the 1970s, examines the word “nation” and the concept of a “patria” or fatherland. His poem “Nación” recalls the words of Hermann Hesse as the poetic voice wants to return to the idea of nation: “Trato de recorder [sic]/ y me llega la duda/ si fue Universo o Madre Tierra/ lo que dijo Hermann Hesse” (484), a stanza translated by Randall as: “I try to remember/ but can’t/ if Hermann Hesse said/ Universe or Mother Earth” (485). Thus, Domínguez’s poetry traces a path, through recollection, through returning to the word, to the concept, in order to understand “patria” within the simultaneous contexts of country, region, planet, and cosmic awareness. In this sense, “Nación” follows the trajectory of historical continuity—as in the case of “Mujer negra” by 1944-born Nancy Morejón—and a José Martí-style articulation of the Cuban as a global citizen. Domínguez underscores this continuity in his poem “Rostros” with the verse: “Y de un rostro llego o regreso a otro” (482), translated as “And from one face I move on to another” (483). This sense of continuity is in keeping with the shifts and trends described by Randall in the introduction, especially what she notes in post mid-twentieth century Cuban poetry: “a rejection of solipsism and an understanding that mind and body, politics and humanity, history and memory are of a piece” (19). Therefore, this book comprehensively plots the trajectory of a poetry where subjectivities—or personal and collective paths—cannot but converge.

In this book, the many paths of Cuban poetry yield to crossings informed by the historical and the political as well as to the adventurous ways of migration and/or the complex routes toward or from exile. The poem “Caminos” by Cleva Solís—born in Cienfuegos the second decade of the twentieth century—offers the necessary guidance into the overall map found in the anthology via the verse: “Existe solo el camino, el camino” (98), translated as “Only the road exists, only the road” (99). Only the road, and not the only way or the sole path, conveys the poem by Solís. It poses a possibility for exploration, and Randall takes avail of its potential and gives title to the book after this frank verse. The road—comprised of stops and detours—signals ideas such as: process, progression, connection, and metaphorical bridges to the Caribbean, the Americas, and the world. Because, as Reina María Rodríguez’s poem “Las islas” warns: “mira y no las descuides./ las islas son mundos aparentes” (334). As Randall masterfully translates these initial verses: “see that you don’t abandon them./ islands are imaginary worlds” (335).

Only the Road/ Solo el camino is, as the subtitle communicates, an anthology of Cuban poetry. Moreover, it is a complex set of routes into poetry itself and the art of translating when context is the constant companion along the way. Margaret Randall’s keen translation and vast knowledge of the subject area make this bilingual edition an excellent contribution to Cuban literary studies, cultural/poetic translation studies, and a recommended addition to the personal bookshelves of readers of Cuban, Caribbean, Latin American literature and poetry in general.

Nancy Bird-Soto