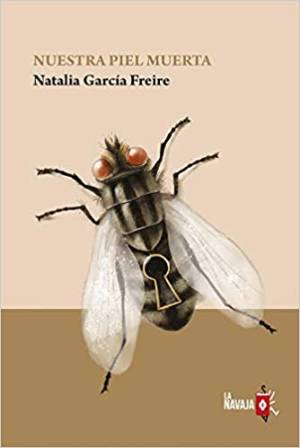

Nuestra piel muerta. Natalia García Freire. Madrid: La Navaja Suiza. 2019. 156 pages.

The pages of Nuestra piel muerta [Our dead skin] smell of damp earth, of decay and of dried flowers; as we the readers turn the pages, we feel the sun burn our skin, seeming even to smother us until suddenly, along with the protagonist, we are wrapped in the thick night fog and we breathe again. What kind of trick is this? There is none, I assure you. What is happening is that, this novel, Ecuadorian author Natalia García Freire’s literary debut, in addition to transporting us to the underground universe of insects, reestablishes the man-earth connection, as if it were giving us another sense; it allows us to observe everything in our surroundings more intensely than ever.

The pages of Nuestra piel muerta [Our dead skin] smell of damp earth, of decay and of dried flowers; as we the readers turn the pages, we feel the sun burn our skin, seeming even to smother us until suddenly, along with the protagonist, we are wrapped in the thick night fog and we breathe again. What kind of trick is this? There is none, I assure you. What is happening is that, this novel, Ecuadorian author Natalia García Freire’s literary debut, in addition to transporting us to the underground universe of insects, reestablishes the man-earth connection, as if it were giving us another sense; it allows us to observe everything in our surroundings more intensely than ever.

The story is that of a family that no longer exists, of a childhood destroyed, of a home invaded by two foreigners. Lucas, the protagonist, tells us the story through a monologue directed at the father, who has been dead now for a long time. The gradual reconstruction of events, in which references to the present and the past alternate, sheds an increasingly new light on the deceased, who instead of a victim turns out to have been a cowardly and dishonest individual, deserving of the hate his son feels. In the novel there is fear, deceit, madness, and revenge, and the pain that comes from these things is so vividly described that it is tangible: “Me gustaría gritar, padre, como un desaforado, con gritos roncos, gruesos, que salieran de mi laringe seca y sucia, dejar salir mis gritos guardados, conservados con violencia. Quisiera sacudir la cabeza ahora mismo como un loco y que los gritos no parasen” [I’d like to scream, father, like someone out of control, with deep, hoarse screams, emerging from my dry and dirty larynx, release my pent-up screams, violently restrained. I’d like to shake my head right now like a madman and for my screams to never end]. Also, the tragic ending becomes increasingly palpable, thanks to a series of omens that invite the reader to proceed cautiously and prepare themself for some kind of ill-fated occurrence: “Después de mucho tiempo acompañados de los bramidos de las vacas, amanecimos envueltos en silencio, como si la casa se hubiese llenado de susurros que decían: escóndete, cállate, quédate quieto” [After long hours hearing the cows bellow, we awoke wrapped in silence, as if the house had filled with whispers that said: hide, stay quiet, stay still].

But that is not all, because the book is also a tender portrait of the affection that Lucas nurtures for Josefina, the mother, and is above all a hymn to the vitality of the earth, to nature in all of its forms. The abundance of details we are given regarding flora and fauna is due not only to the curiosity the protagonist has inherited from his mother, but also to a deeper awareness the two share, about the perfection of those kingdoms in contrast to those of men. Is it not true that while every human gropes about in the darkness of his path, unpredictable and incomplete, like puppets at the mercy of luck, insects—almost imperceptible in their industriousness—give life to a microcosmos that despite always being in motion turns out to be reliable, imperturbable, eternal? And if someone were to still have doubts about our true vulnerability, the plot itself provides an example of this when it brings about the collapse of an entire family as a result of an event so banal as the unexpected arrival of two guests to their home.

Of particular note in the series of dramas that unfold thereafter is that of Josefina’s commitment to a sanitarium. Her attitude, wholly dedicated to caring for her garden and the study of botany and entomology—that is, engrossed in contemplation not exactly spiritual—must have been unacceptable in a society that at that time (it is understood that we are approximately at the beginning of the 20th century) assigned women the rigid role of mother, wife, and devout woman. Therefore, while the town had been quick to brand her mad for not being baptized and not going to mass, only the son had been able to decipher the key to her marvelous world and understand the total fusion that had occurred between her and the earth: “A veces pensaba que cuando mi madre se desnudaba y se metía en la tina que preparaba Esther era para mojar pequeñas raíces que le salían de los sobacos y las ingles” [Sometimes I thought that when my mother undressed and got into the bath that Esther would draw it was to soak the small roots that grew from her armpits and groin].

Indeed, the struggle between religion, science, and madness gives life to the entire text, going so far as to place the world of men face to face with the animal kingdom also from a moral point of view. The Christian precepts, embraced conspicuously by the father as well as the other characters, are reduced in the words of the narrator to a mere question of superstition and appearances, centered on a cruel and capricious God. Lucas and Josefina juxtapose that credo with the worship of insects, a clear example of purity, chastity, harmony, and justice. And in effect, what the novel allows us to observe is the contrast between the human side of animals and the animal side of humans: it is the latter who consistently cause suffering for their fellow man and sully themselves with the worst of crimes. In light of this consideration, Lucas’s desire to wriggle out of his skin to metamorphose, to become another life form, fruit of the earth, is finally explained: “Quiero licuar mis vísceras, olvidar mi lenguaje, enredar las palabras y salir de este cuerpo” [I want to liquify my bowels, forget my language, jumble up the words, and leave this body].

That being said, the success of this work is without a doubt due in large part to the uniqueness of its argument, but what also makes Nuestra piel muerta an exceptional piece is its style, characterized by poetic and evocative language, rich in metaphors and suggestive imagery; one could even define the atmosphere surrounding Lucas’s return to his family home as oneiric, a scene that to those who love Juan Rulfo is reminiscent of Juan Preciado’s trip to Comala. Despite this lyricism, the language employed by the writer is free of presumptuousness, running through the text is a vocabulary that is essential, basic. The same words appear time and again, clearly not a sign of carelessness but the opposite: instead of making the rhythm tiresome, the use of repetition makes it more fluid, lending it the cadence of a melody, or perhaps a litany. And do not think that the use of a poetic tone implies in and of itself the absence of prosaic references: one of the author’s greatest achievements is precisely the ability to paint in exact and vivid brush-strokes the human body in its least pleasing and even repugnant aspects.

Nuestra piel muerta, in the end, is a work capable of elevating the reader to poetry and, at other times, pulling the reader down. But more than anything it is a journey to the bowels of the earth and to those of human beings, at the same time. Who would have thought that a novel so overflowing with animals, insects, flowers, and shrubs could teach us so much about ourselves?

Arianna Tognelli

Translated by Michelle Mirabella

Arianna Tognelli is a graduate of the University of Bologna with a degree in Modern, Comparative, and Postcolonial Literature.

Michelle Mirabella’s translations have appeared in World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, Your Impossible Voice, and Exchanges. She is currently pursuing an M.A. in Translation and Interpretation at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey. She has roots in Pittsburgh, Chile, and New York.