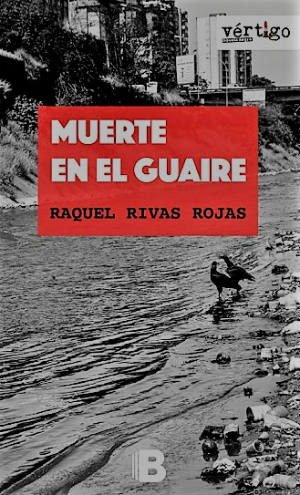

Muerte en el Guaire. Raquel Rivas Rojas. Caracas: Ediciones B. 2016. 156 pages.

The first novel published in print format by Raquel Rivas Rojas (Guanare, Venezuela, 1962) forms part of “Vértigo,” a new collection of detective fiction that began publication in Caracas at the end of 2012 under the direction of the writer Mónica Montañés, known within and outside Venezuela for her theatrical productions and her television screenplays. Despite the precedent of the series “Alfa 7,” conceived by Leonardo Milla for Editorial Alfa and published between 2005 and 2008, this is the first time in Venezuela that the directors of such a project have sought out works of fiction in which women characters are the protagonists. In fact, all the books published thus far in the “Vértigo” series have told stories of violent acts committed by or against women, in which women solve or narrate the cases, as in Muerte en el Guaire [Death on the Guaire]. The collection is also important for advertising a group of writers, mostly trained and known as journalists, which includes a significant number of women. The editors even include a piece whose protagonist is a transgender woman (Guararé by Wilmer Poleo Zerpa).

The first novel published in print format by Raquel Rivas Rojas (Guanare, Venezuela, 1962) forms part of “Vértigo,” a new collection of detective fiction that began publication in Caracas at the end of 2012 under the direction of the writer Mónica Montañés, known within and outside Venezuela for her theatrical productions and her television screenplays. Despite the precedent of the series “Alfa 7,” conceived by Leonardo Milla for Editorial Alfa and published between 2005 and 2008, this is the first time in Venezuela that the directors of such a project have sought out works of fiction in which women characters are the protagonists. In fact, all the books published thus far in the “Vértigo” series have told stories of violent acts committed by or against women, in which women solve or narrate the cases, as in Muerte en el Guaire [Death on the Guaire]. The collection is also important for advertising a group of writers, mostly trained and known as journalists, which includes a significant number of women. The editors even include a piece whose protagonist is a transgender woman (Guararé by Wilmer Poleo Zerpa).

Rivas Rojas emerged as a writer in print with El patio del vecino [The neighbor’s patio], a remarkable volume of short stories published in 2012 (Caracas, Editorial Equinoccio, Universidad Simón Bolívar). Nonetheless, readers first got to know her chronicles, stories, and first novel in 2008, with the launch of the blogs Notas para Eliza [Notes for Eliza], Cuentos de la Caldera Este [Stories of Caldera Este], Apuntes para juego [Notes for game] (her first novel, written in 1988), and Barrio Chino [Chinatown]. With a degree in Social Communication (1985) from the Universidad Central de Venezuela, a master’s in Latin American Literature (1992) from the Universidad Simón Bolívar in Caracas, and a doctorate in Latin American Cultural Studies (2001) from King’s College, London, the author worked until 2008 as a professor of Latin American Literature in the Universidad Simón Bolívar in Caracas. That year, she moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, where she now works as a translator. In short, Rivas Rojas is an intellectual with solid educational foundations, a deep knowledge of modern literature and literary criticism, and a professional practice that has gradually widened to include articles in peer reviewed journals, three books of essays, and, in the past decade, literary prose.

In Muerte en el Guaire, Sere, a journalist-turned-restaurateur (she is head chef at La Factoría, a fictional restaurant in Caracas), sends a series of letters to her friend Olga, a Venezuelan writer living in London. At first, the letters tell how the dismembered corpses of five young men, all “well fed” with “athletic and muscular bodies,” were pulled out of the Guaire River, which flows through Caracas. In short order, two further cases are added to the mix: those of two childhood friends, Antonio Peralta and Carlos Ramírez, whose bodies are found intact, allowing investigators to determine their identities. The events that follow are narrated in a linear fashion as Sere learns about the results of the search directed by Patricia, a journalist, assisted by Lena, a pathologist friend of Patricia and Sere; Natalia, a lawyer specializing in Human Rights; and two police officers: Gutiérrez, a detective who was involved in solving the initial cases, and Commissioner Ferrer, who, although supposedly retired, maintains an archive of unsolved cases into which he makes occasional inquiries.

The story, built out of twenty-three short chapters with the fast-paced style and familiar language of letters between friends, focuses primarily on the case of Antonio Peralta. This young man studied Education at the Universidad Central de Venezuela and formed part of one of the groups known as “colectivos” (“collectives” in English): armed civil organizations that emerged under the regime of Hugo Chávez. One decisive character in the investigation is Mariela, the ex-girlfriend of Antonio and the niece of Celia Salas, a high-ranking official in the Venezuelan government. The murder of Carlos Ramírez also receives attention; in fact, this is the case that connects the book most closely to the Venezuelan government. In the end, thanks to some help from her friends, Patricia manages to solve the two cases; as in any good detective novel, the resolution of the main crime will be a surprise for the readers.

To some extent, Muerte en el Guaire can be read as the counterpoint to El patio de vecino, which also focuses on female protagonists, all of whom live in Great Britain and write based on their experiences as immigrants. In particular, the book includes many intertextual references to “La vida de los otros” [The life of others] (23-40), which is also constructed based on letters that a character writes to a Venezuelan friend living in Caracas. The connections are even stronger with two stories from the same collection whose plots tellingly take place in Venezuela: “La escena del crimen” [The scene of the crime] (165-172), and especially “Final con cadáver” [Ending with cadaver] (157-163), which includes a police officer named Gutiérrez who works in the Caracas morgue and investigates the case of a dead man found in the Guaire River. This story seems to represent the novel in its embryonic form.

Readers of recent Venezuelan fiction—much of which is being written outside of the country—will notice that Rivas Rojas coincides with other writers of the diaspora like Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez (Los maletines [The briefcases], 2014) and Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles (Jezabel [Jezebel], 2013) in the creation of works that tell of the precarious nature of life in Venezuela under the governments of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro. In short, these are stories that demonstrate the profound failure of a nonsensical political project that has submitted the country to the worst economic crisis of its history as a republic (inflation hit 700% in 2016); to extreme levels of violence, unprecedented in the nation’s history (28,479 homicides committed in 2016, according to the Venezuelan Violence Observatory, for a rate of 91.8 out of 100,000 citizens, one of the highest in the world); and to approximately 2,500,000 migrants leaving the country since Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999. For all these reasons, the crime novel has become one of the most common forms for writers living outside of Venezuela to tell stories of violence, as horrifying as they are necessary to provide an accurate idea of how Venezuelans have lived in recent years.

The fruit of learned experience with many genres, both literary (detective novels, epistolary stories, sentimental fiction, metaliterature) and non-literary (personal diaries, police chronicles, journalistic reporting), this important tale from Rivas Rojas is a successful text of hybrid, agile prose that will doubtless become a key work in the study of the literary treatment of chavismo. I recommend this book to anyone interested in Venezuelan crime fiction—a category that boasts ever more proponents (Marco Tarre Briceño, José Pulido, Ana Teresa Torres, among others) thanks to the publication of the “Vértigo” series by Ediciones B Venezuela—and/or to those who wish to acquaint themselves the rich literary production of contemporary women writers. Raquel Rivas Rojas is a relatively recent arrival on this scene, but she is already an indispensable reference.

Wilfredo Hernández

Allegheny College