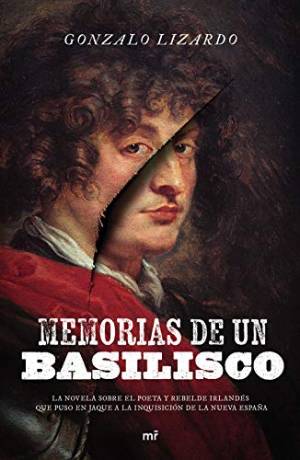

Memorias de un basilisco. Gonzalo Lizardo. Mexico City: Martínez Roca, 2020. 648 pages.

As a preamble to this review, I am usurping William Lamport’s words: “¡Cristiano lector!, no es esta obra para los cobardes espadachines de la ley del duelo […] ni es tampoco para los cerrados bronces de corazón empedernidos […]” [“Christian reader!, this is not a work for the cowardly swordsmen of duelling laws […] nor is it for those enclosed bronzes of inveterate hearts […]”] (Cristiano desagravio [Christian apology]). Memorias de un basilisco [Memoirs of a basilisk] is an ambitious work that can be intimidating in an age marked by urgency and brevity. But Gonzalo Lizardo knows how to capture us from the first pages by offering the readers the unusual spectacle of attending, as witnesses, to an unprecedented auto-da-fé. This setting works to portray the multi-colored viceregal society of New Spain in a fresco, and to thus display the complex social fabric of that time. A large crowd gathers to witness the burning of the prisoners sentenced to death, most of whom are heretics, and, among them, one stands out in particular—the Irishman Guillén Lombardo, el Basilisco (the Basilisk).

As a preamble to this review, I am usurping William Lamport’s words: “¡Cristiano lector!, no es esta obra para los cobardes espadachines de la ley del duelo […] ni es tampoco para los cerrados bronces de corazón empedernidos […]” [“Christian reader!, this is not a work for the cowardly swordsmen of duelling laws […] nor is it for those enclosed bronzes of inveterate hearts […]”] (Cristiano desagravio [Christian apology]). Memorias de un basilisco [Memoirs of a basilisk] is an ambitious work that can be intimidating in an age marked by urgency and brevity. But Gonzalo Lizardo knows how to capture us from the first pages by offering the readers the unusual spectacle of attending, as witnesses, to an unprecedented auto-da-fé. This setting works to portray the multi-colored viceregal society of New Spain in a fresco, and to thus display the complex social fabric of that time. A large crowd gathers to witness the burning of the prisoners sentenced to death, most of whom are heretics, and, among them, one stands out in particular—the Irishman Guillén Lombardo, el Basilisco (the Basilisk).

The author triggers our curiosity because he formulates a compulsory question: who is this enigmatic man that summons crowds with his execution? That is what the novel is about, revealing a character so slippery that he has earned the nickname of Basilisco, also known as el Zorro (the Fox) and el Azucena (the Lily), because of how he woos the ladies using his poetry. By publishing this book, Lizardo culminates the work he began years ago, fascinated by this enigmatic character. As an academic, after much thorough archival research, he published and edited the manuscript of Cristiano desagravio y retractaciones de Don Guillén Lombardo [The Christian apology and retractions of Don Guillén Lombardo] (2016). Lizardo’s idea was to show the historical character’s own voice through the publication of one of his main manuscripts, especially because of the past controversies surrounding him.

This character was first dealt with by Vicente Riva Palacio in his novel Memorias de un impostor [Memories of an impostor]; later, Luis González y Obregón aimed to demystify Lombardo’s fictionalized figure in a book faithful to historical truth; and, finally, Gabriel Méndez Plancarte translated his collection of poems Regio Salterio [Royal psalter]. It must be said that, in the novel, these three authors appear as characters, mentioned in two different passages as clerks that help with the restoration of records in the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. A homage, no doubt, by Lizardo, and a nod that situates his novel as part of the lineage of Lombardo scholars. See the title, almost homonymous to Riva Palacio’s while keeping its distance.

Riva Palacio’s novel is faithful to the chronological development of events from the moment Lombardo is incarcerated until his death. This is unlike our novel, for, as we mentioned, its starting point is Guillén Lombardo’s death. The story is presented as if it were a thriller because, in the face of the character’s execution, there are unresolved mysteries, such as the cause of his death and the mixed feelings it provokes in the audience. The novel is structured into four chapters or misterios (mysteries), and each of them is accompanied by a map that anchors the text to the substantiated historical past.

The novel has an agile rhythm in which several voices are rotated. We have the voice of a third-person narrator that conducts the story and calls upon other characters when appropriate. And Guillén Lombardo’s own voice, too, when we partake in the memoirs he writes while he is imprisoned, and which are precisely the ones that ended up being captured in his works. Lombardo’s writing is left shrouded in a veil of mystery, and there are few explanations as to how he could write with such rudimentary means while in captivity. The way of solving this is through another character: Jezabel. A kind of “daemon tan encantadora y suspicaz” [“daemon, so charming and suspicious”] that appears and disappears from his cell and who is a zealous custodian of Lombardo’s memoirs. Writing has a relevant role that, though not capable of saving Lombardo from death, can surely vindicate him, for it is also the testimony that the Holy Inquisition takes up in order to condemn him for his own words and to protect themselves from accusations.

Lombardo unveils his life through the memoirs he writes in prison. From him, we learn about his Irish past and his desire for adventure and justice, as well as the multiple journeys he takes through Italy, Germany, and France before arriving in Spanish territory and enlisting to serve the crown. His arrival in New Spain is controversial—for some, he came intending to occupy the viceroy’s seat, emancipate Black slaves and bring justice to Indigenous people; for others, he had the bad luck of getting entangled in Palafox and Mendoza’s schemes to oust the Marquis of Villena.

Another merit of the novel is that it develops, parallel to Guillén Lombardo’s life, the story of Inés and Sebastián Carrillo, two siblings who own the Mesón de los Carriones and who are attached to Lombardo. I dare say they carry the weight of the chronological story after el Basilisco’s death, and that the events that unfold are interwoven with the past to reveal why he ended up at the stake.

Inés enters the service of Juan de Mañozca, bishop inquisitor in charge of Lombardo’s trial, and it is through her gaze that we enter the framework of life in New Spain. Above all, we learn about the sumptuous life that “monseñor de las ratas” (Monsignor Rat)—and, thereby, the high clergy in charge of executing sentences—leads. Lizardo reveals the opulence and power held by the Church hierarchy, in contrast to the religious orders, and his task is to balance the layered world of New Spain. There is a detailed and well-researched look at the role of the Church that, through its zealous caretakers, maintained order in the emerging Mexican nation.

For his part, Sebastián Carrillo, following in his father’s footsteps, was employed as a clerk in the Tribunal; at one point, he was forced to abjure Guillén Lombardo, even though Sebastián felt an affinity towards him. But Sebastián knows that the Irishman’s death was caused by political intrigues, which he tries to prove by accessing the Holy Inquisition’s records, and, while he’s at it, exposing a corrupt system that acts to defend its own interest. To achieve this, he plots with Antonia de Castro, Guillén’s former fiancé, to unmask those who executed the sentence against Lombardo, and to free his sister from the persecution to which she falls victim when the bishop finds out she possesses a copy of the Regio Salterio, a profane book that can shed light upon Lombardo’s life and process.

“¡Vaya tarea que nos espera: ordenar, leer, razonar justamente tanta palabrería!” [“What a task awaits us—to order, to read, to precisely reason such verbiage!”]. It is worth reading because Gonzalo Lizardo manages to give voice to Guillén Lombardo, and, through an intersection of voices and stories, the reader is left with the task of passing judgment. This is a novel that rescues the character, that triggers our curiosity for the historical truth, and that fluently displays the past, so present still, of our viceregal history.

Ramón Alvarado Ruiz

Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí

Translated by María Guadalupe Elías Arriaga

Ramón Alvarado Ruiz earned his doctorate in Arts and Humanities from the CEMARTH, Monterrey. Since 2014, he has worked as a research professor at the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí and has been a member of the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores and the UC-Mexicanistas research group. His main line of research is twenty-first century Mexican and Latin American literature, with an emphasis on the five writers of the “Crack” group. He has published “The Crack Movement’s Literary Cartography (1996-2016)” (2017); “Santiago Gamboa y Jorge Volpi, una mirada compartida de una narrativa global y local” in Estudios de Literatura Colombiana (2018); “Las elegidas, de Jorge Volpi: del plano general al close-up narrativo” (2019); and the book Literatura del Crack: un manifiesto y cinco novelas (2016).

Guadalupe Elías (San Luis Potosí, 1987) is a translator, educator, and researcher. She earned her doctorate in Latin American Studies from the University of St Andrews, Scotland in 2019. She has taught Spanish as a foreign language at the university level, as well as classes on Spanish and Hispano-American literature and film. As a translator, she has participated in various projects, including EU-LAC MUSEUMS, coordinated by the School of Art History of the University of St Andrews and funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program. She currently works as an independent translator.