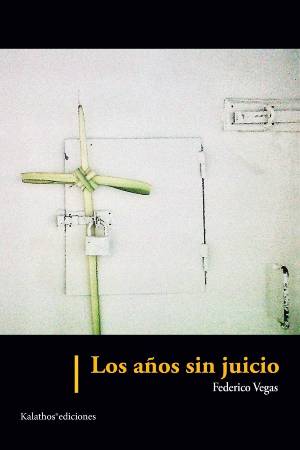

Los años sin juicio. Federico Vegas. Madrid: Kálathos. 2020. 428 pages.

There are stories that land in reality on all fours, like wild animals determined to root out and show us the evils we face. That is the case of Los años sin juicio [The senseless years]1, the most recent novel by Federico Vegas, in which, through the story of a man who has fallen from grace, the reader finds a tool to interpret the absurdities of reality, process randomness and counter injustices. It is such a vivid account that we cannot resist the artifice and have no choice but to let ourselves be carried away by the fiction towards reality.

There are stories that land in reality on all fours, like wild animals determined to root out and show us the evils we face. That is the case of Los años sin juicio [The senseless years]1, the most recent novel by Federico Vegas, in which, through the story of a man who has fallen from grace, the reader finds a tool to interpret the absurdities of reality, process randomness and counter injustices. It is such a vivid account that we cannot resist the artifice and have no choice but to let ourselves be carried away by the fiction towards reality.

The novel forms part of the long tradition of testimonial fictions written during the dictatorships of Juan Vicente Gómez and Marcos Pérez Jiménez. A prison literature that erupts in Venezuela with each oppressive regime and includes such foundational texts as Puros hombres [Only men] (1938) by Antonio Arráiz, which warned the reader on its cover that by turning the page they would be entering prison. In dialogue with this tradition, Vegas builds a story so convincing, so detailed and so rich in references that it is almost impossible to recognise it as a fictional construct. A novel that could well be included among those stories crafted with the express intention of erasing the limit that separates them from reality. They are texts that construct a present, as Josefina Ludmer maintains, and in doing so force us to experience the world around us in a different way.

It is a device that Vegas has been perfecting since Falke (2005), his first historical novel, in which he borrowed his uncle Rafael Vegas’s voice to recount the failed invasion by a group opposed to Gómez’s regime. He further explored this mechanism in his two subsequent historical novels, Sumario [Summary] (2010), which recounts the assassination of Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, and Los incurables [The incurable] (2012), which focuses on the final months of the painter Armando Reverón. Los años sin juicio is also based on a true story. In this case, the arbitrary detention of four executives of a finance company accused, through a direct order from Hugo Chávez, of a series of crimes that were never proven. The executives spent three years under arrest, attending hearings that went nowhere and waiting for a sentence that never came.

Based on the experience of one of the prisoners, Herman Sifontes, the novel is a first person account of the three years that the executives spent in prison, subject to the will of the caudillo and the arbitrariness of a regime that is corrupt to the core. The novel unfolds through a fragmentary and pendulous structure that jumps from one topic to another, returning time and again to some obsessions that demonstrate the mental state of the prisoners, whose conversations keep going over the same topics. Although the first chapters narrate the series of events that led to the arrest sequentially, once in jail time seems to stagnate. From then on, the stories occur in an episodic way and the narrator tells, in small vignettes, anecdotes about each of the characters that accompany him in prison, returning to the costumbrista attempt to capture people and customs in minute detail typical of prison literature of the previous century. In many cases, the reader can look up these characters online to verify their real identity.

Through these stories, we can observe the range of crimes, but also irregularities, that make up the population of a prison bringing together a sexual predator with a drug dealer, an unredeemed paramilitary with two health professionals who are victims of the fury of a high-ranking military man, decent guards with psychopathic henchmen. Although the fiction clearly displays the extremes of cruelty that some police officers are capable of reaching, the overall result is a universe in which the inmates end up as part of the same human group that only establishes differences between those who are inside and those who are outside. Each of the characters is presented in all their human dimensions, without caricaturing or condemning them.

In this way, the novel distances itself from Manichean, polarizing or simplifying representations, showing a microcosm where complex and contradictory characters coexist. A scene that can well be read as a metaphor for the country itself, in which both those who govern and those who suffer under the chavista regime are trapped. The deprivation, the scarcity, the lack of comforts and the absence of hope affect everyone equally. In Los años sin juicio, then, we see the many meeting points where the boundaries dissolve between government and opposition, those within or outside the law, guilty and innocent, in clear opposition to the exclusive imaginary flourishing in recent Venezuelan literature, where everything seems to be black or white.

Nonetheless, Los años sin juicio is also a story that appeals to a universal condition, that of the impotent man in the face of absolute power, that of the subject trapped in a Kafkaesque net, waiting for others to decide his fate. In the final third of the novel, now in a second prison and under an even more restrictive regime, the narration takes on an intimate tone and the big themes emerge: loneliness, guilt, hopelessness, looking back over one’s life to explain the present, the impossibility of imagining the future. But, as happened in real life, the strong man who kept them in prison dies and, in the same arbitrary way as they were arrested, the executives are freed with minimal legal procedures. Yet when they leave prison nothing is the same and the story ends with a man alone in an empty house, or in other words, the universal drama of a man who is prisoner of his own freedom.

With Los años sin juicio, Vegas has achieved a novel in which nothing is superfluous, where fiction reaches a state of such transparency that it becomes an accurate portrait of reality. This success is due to the fact that the author has been able to combine his ability to delve into history with his undeniable gift for constructing the present through words, combining the skills of a novelist and the attention to detail of a chronicler. The result is a novel that bites and sniffs, probing and rummaging in our ambitions and our deepest fears, showing us that when you live under a dictatorship the whole country becomes both a treasure trove and a prison. What this novel shows us is that, under a totalitarian regime, no one is completely innocent and, at the same time, we are all always one step away from being submitted to the most outrageous arbitrariness.

Raquel Rivas Rojas

Translated by Katie Brown

1 The title is a play on words, as “sin juicio” means both without a trial and without sense.