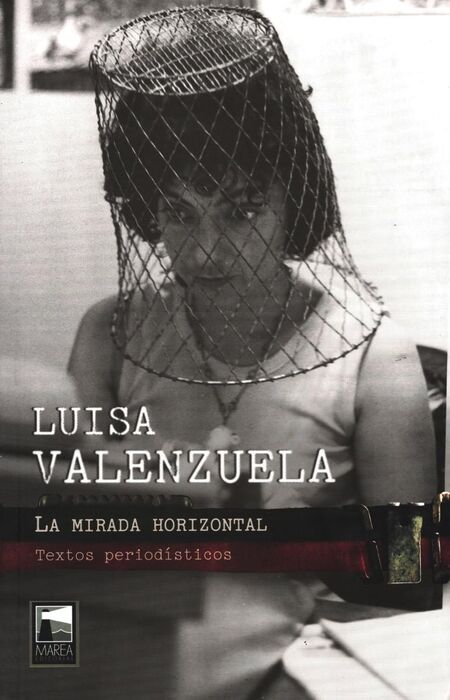

Buenos Aires: Marea Editorial SRL. 2021. 298 pages.

In the prologue to this treasured compilation of Luisa Valenzuela’s journalistic work, Marianella Collete details an extensive amount of material that has long been kept away from readers, like recovered writing on the yellowish patina that only time can give. Judiciously, many of Valenzuela’s writings have reawakened for new readers.

In the prologue to this treasured compilation of Luisa Valenzuela’s journalistic work, Marianella Collete details an extensive amount of material that has long been kept away from readers, like recovered writing on the yellowish patina that only time can give. Judiciously, many of Valenzuela’s writings have reawakened for new readers.

La mirada horizontal: Textos periodísticos (2021) presents some historical events that interestingly coincide with what is currently happening in Latin America. The socio-political structure in journalistic writing allows for profiles such as “¿Groucho Marx en la Argentina?” (Gente magazine, 1974) to rattle the colorful personality of the person conversing with Valenzuela, while describing how wrestlers move in the ring. Through a profound gaze disguised as “Sí, Martín Karadagián,” “La vida, los dichos y los enigmas de Karadagián,” or, “No hay que copiar, hay que inventar,” the chronology of a wrestler’s memory is highlighted, as are his feelings, matches, rules of the game, and masks during the ritual of entering the ring. The description of this man exalts a resemblance to literary characters given that, according to Valenzuela, literature and journalism have always been her vertical and horizontal axes that intersect to tell it all.

Parting from this communion in her journalistic writing, Valenzuela once again turns toward literature with “Filloy del derecho y del revés” (Suplemento Gráfico, La Nación, 1968.) In it, Juan Filloy speaks of an imaginary writing that he describes with two sacred guidelines: “the characters of a fruitful soul and absolutely hating euphemisms.” That is to say, the words of an author can be as harsh as the truths of a journalist. As in Valenzuela’s case, a journalist can also describe the writer as someone who must accept an axiom to write and be read. There is a back-and-forth in the real world of cultural journalism that is voiced in every single one of her lines.

And it goes further. When a journalist and author interviews another journalist and author we shift to a complex exchange of gazes. In her piece “Encuentro con la mexicana Elena Poniatowska: Libros como espejos” (La Opinión, 1977) the marvelous hide-and-seek game mentioned in her first lines begins. Here, Poniatowska describes herself, Elena, as someone hiding and peeking out while walking past the heavy artillery of her distinguished family. When referring to her brother Jan, her mother’s mutism, or the inability to express emotions inherited from her European ancestors, the readers contemplate once again, many years later, that game of mirrors where a certain shared silence has always been reflected. Because, in Valenzuela’s work, words always have a dynamic nature of communication and exchange. In the context of what it means to interview an author, who was also a philosopher and essayist, I would like to mention a conversation she had with “Susan Sontag: La amante de los amantes” (El Cronista Cultural, 1992). In it, Valenzuela describes a friendly conversation they had at Sontag’s home, where they talked about their lives as protagonists “contaminated by literature.” The joy of sharing a vision, a way of interpreting the world, then shifts into the precious power of words, where certain dynamic and independent fascinations, such as volcanoes or polychrome, confer fascinating forms of descriptive power that, in Sontag’s case, lead us to an alleyway of conscience.

Let us turn to that veiled place where Salman Rushdie can be found, with whom Valenzuela met earnestly. In “Encuentro con Rushdie” (El Cronista Cultural, 1992), the so-called Mr. Satanic Verses is the central figure of a text that Valenzuela writes under the disillusionment of a narrative “cut-short” by the tyranny of written journalism. However, her words are illustrated and strengthened by details of what happened, of that button they wanted to share with the audience that said “I am Salman Rushdie,” and of the uneasiness of the applause. Later, in the postscript where William Styron and Peter Mahiessen join Valenzuela, away from the tyranny, a final conversation unfolds that encourages the questioning of all of the above (as currently happens in social media, where the conversations following the initial dialogue grow stronger than the one on the actual event.)

Bringing light to her chronicles as a precious way of writing history, in “Homenaje a las madres de Plaza de Mayo” (El Cronista Cultural, 1991) Valenzuela mentions a likely cyclical repression. Referring back to the linearity of the horizontal gaze in the title, “those who wanted, want, and will continue to want silence or oblivion preach linearity and straightness, which is not a synonym for rectitude but rather the opposite,” like the unfortunate paradox of the memory of the disappeared, of the white silhouettes, of the mothers. The mothers of Plaza de Mayo are not forgotten, and rereading their detailed description in her work helps their memory to remain a shared responsibility.

This archive of memories is multiplied by the work compiled in the book. By revisiting everything that Valenzuela mentions regarding the work of Julio Cortázar and Carlos Fuentes, or her political views on Hugo Chávez, readers can analyze what has already happened, but with the valuable addition of the twists and turns that have taken place. An open and historic re-read, like the possible interpretation of those of us who have survived the worst of it. It is a book that continues to resonate.

To conclude, and given the current zoonotic disease, it is worth revisiting “Palabras nuevas y Cristóbal Colón” (El Cohete a la Luna, 2020), where Valenzuela outlines how Covid-19 is disproportionately affecting African-Americans not due to genetic factors, but rather due to cruel socio-political reasons. She then discusses George Floyd’s case to emphasize that silent racism also affects indigenous people, in a pathological and unjust socio-political context, such as the one we have sadly witnessed in recent years. Will there be more battles against ourselves? The answer to the anxiety that readers feel when finishing this book will surely be addressed in future writings about what happens next, under the valuable gaze of Luisa Valenzuela.